Translating Urban/Translating Ritual: An Ethnographic Study of Dev Uthan Ekadashi

UPES, Dehradun, Uttarakhand

Indian Institute of Technology Mandi

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3122-881X

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3122-881X

Abstract

Gurugram—a city located near Delhi, in the state of Haryana—is an important contributor to the country’s information technology, finance, and banking sectors. Geographically, it offers a rich amalgamation of the urban and the rural; while the urban is an eclectic mix of regions and religions, the rural is still rooted in folkloric traditions. One such tradition is Dev Uthan Ekadashi: celebrated around ten days after Diwali, it marks the awakening of Lord Vishnu from his four-month long sleep, which symbolises a fresh beginning to the Hindu wedding season. To mark the occasion, this cosmopolitan city’s Haryanvi Hindu women gather to create illustrations, sing folksongs, and perform several rituals.

In this paper we examine Gurugram as a site of translation by analysing data collected through two sessions of ethnographic fieldwork, conducted in November 2021 and November 2022. We investigate the relationship between the ritual and the space, both of which, we argue, undergo translation; furthermore, we posit that the women performing the ritual become cultural agents within a postcolonial space. Thus, our study establishes Gurugram as a translational city, demonstrating resistance where the folkloric tradition is kept alive through cultural meanings shaped by language interaction.

Keywords: translation, urban space, Gurugram, Dev Uthan Ekadashi, India, ritual.

INTRODUCTION: TRANSLATION, CULTURE, CITY

As a field of inquiry, Translation Studies has moved from an initial emphasis on equivalence or faithfulness (to the source text) to a cultural approach in which the focus is on redefining the context and the conditions of the translation process. Such an approach sees translation as a form of rewriting. Analogously, the 1970s and 1980s marked a transition for anthropologists, as they questioned their right to interpret other realities and decide what can/not be represented (Murphy and Dingwall 344–45). As a result, scholars began to perceive ethnography as a translation of sorts. In the early 2000s, influenced by Bourdieu’s work, significant research on ethnographic studies in translation was conducted (e.g., Buzelin; Wolf).

There have been various ethnographic approaches to translation: while some studied the agency of the translator (Basalamah), others examined the process in indigenous and postcolonial contexts (Rafael, Contracting Colonialism). For instance, in Translational Justice, Rafael argues for the role of translation in challenging colonial hierarchies, and encourages adopting decolonial ethics in translation practices (210–19). Indeed, an interdisciplinary approach—combining history, cultural studies, and ethnography—reveals the unequal power dynamics in translation and the role of indigenous communities in this process (210–19). It is the ethnographic aspect of Rafael’s scholarship that helps foreground the contribution of language, religion, and cultural exchange to shaping colonial relationships; ethnography is shown as capable of revealing gaps in colonial translations.

Similarly, Michaela Wolf brings together translation studies, cultural sociology, and ethnography (“Introduction” 1–36). She argues for the importance of fieldwork, particularly methods such as archival research, participant observation, and interviews to study translators’ lived experiences. Indeed, Wolf demonstrates the influence of several cultural, social, and economic factors on translators’ practices, and it is her employment of the ethnographic-historical methods—e.g., examining camp records, survivor accounts, and oral testimonies—that offers a nuanced understanding of translation as a tool of resistance.

In this paper we examine Gurugram, a city in the North Indian state of Haryana, as a site of translation, by analysing data collected through ethnographic fieldwork conducted in November 2021 and again in November 2022. We investigate the relationship between the ritual and the space, both of which, we argue, undergo translation; furthermore, we posit that the women performing the ritual become cultural agents within a postcolonial space. Thus, our study establishes Gurugram as a translational city, demonstrating resistance where the folkloric tradition is kept alive through cultural meanings shaped by language interaction.

We begin by situating Gurugram historically, geographically, and linguistically, and the city remains the focal point throughout. What follows is an overview of the methodology used for data collection and analysis. Next, we apply to Gurugram the concepts introduced by Sherry Simon (“the translational city”) and Emily Apter (“the translation zone”). Subsequently, we position Haryanvi women as cultural agents and mediators by examining their relationship with the ritual and the city.

GURUGRAM: THE CITY

Haryana is an agrarian state in North India that contributes a major portion of the food grains to the country’s public distribution system. Gurugram District is located 30 kilometres south of New Delhi, the National Capital. Since the turn of the 21st century, the city has undergone rapid development and construction. Its excellent connectivity with other states via the Delhi–Jaipur–Ahmedabad broad-gauge rail link and National Highway 8 brings thousands to Gurugram for work, travel, and entertainment (“About District”). The story of its development, industrialisation, and transformation began in the early 1980s, when Japan’s Suzuki Motors collaborated with Maruti Udyog Limited, thus putting the district on the international map. It is one of Delhi’s major satellite cities, part of the National Capital Region, and is within commuting distance via an expressway and the Delhi Metro. The second largest city in Haryana and its industrial/financial centre (“About District”), Gurugram is also India’s second largest information technology hub, and the third largest financial and banking hub. It has the third highest per capita income in India and is the only Indian city to have successfully distributed electricity to all its households. Today, it houses multinational software companies and industry giants, while its architecture features shopping malls and skyscrapers.

Despite the presence of such an industrially and commercially successful city, the state of Haryana is a picture of extremes. With a skewed sex ratio of 830 girls to 1,000 boys as per the 2011 Census data (“Census of India”), it struggles with misogyny, female infanticide, and honour killings. Within Haryanvi society there is resistance to allocating any property rights to women, as that would further reduce the already small holdings, making such land unprofitable; this, in turn, becomes a major reason for the sons-over-daughters preference (Ahlawat 16).

Haryanvi society also observes strict codes regarding marriage as well as familial, caste, and clan honour, and expectations of dowry. As a result of such oppressively patriarchal structures, women are relegated to the peripheries, where they face violence and bias on an everyday basis. Khap Panchayats, or caste councils, are also responsible for controlling the social, moral, and cultural behaviour exhibited by Haryanvi youth. Despite Khaps not having any legal authority, they continue to exert patriarchal influence. As British colonial administrator E. A. A. Joseph wrote in The Customary Law of the Rohtak District (1911), documenting the local legal customs, “a female, minor or adult is always under guardianship; while single, she is under the guardianship of her father, if he be dead, of other relatives. When married, it is her husband who takes her charge, and when old or if husband dies, her sons take over her” (54–55). Similarly, even married women in Haryana are always expected to adhere to societal rules, also when performing domestic and agrarian roles, and contributing financially to their families. Forced to wear a ghunghat (veil), they struggle to survive and be comfortable in public and private spaces. However, various women-centric rituals such as Sanjhi (Dhandhi and Sigroha) and Dev Uthan Ekadashi offer spaces for self-expression and agency to communicate freely, which is difficult in an otherwise grim setup.

Gurugram—or, as it is still called locally, Gurgaon—is supposed to have ancient roots and to have been in existence since the times of the Mahabharata. According to local legend, Yudhishthira—the eldest of the five brothers known in the Mahabharata as the Pandavas—gifted the village to his guru, or teacher. Hence the name; both -gram and -gaon mean “a village,” and point to the importance of the rural. Gurugram was historically inhabited by Hindus and formed a part of an extensive kingdom ruled by Ahirs. With the decline of the Mughal empire, the region was torn between contending powers. By 1803, most of its territory came under British rule, and after the revolt of 1857, its administration was transferred from the North-Western provinces to Punjab. In 1947, Gurgaon became part of the undivided state of Punjab in an independent India, and in 1966, the city came under the administration of the new state of Haryana (“Demography”).

Hindi is one of Gurugram’s main languages, although many also speak English; other common languages are Haryanvi (including its regional dialects) and Punjabi. The city is multicultural, composed of a variety of religious, ethnic, social, and cultural groups; it is diverse in its distribution of rural and urban areas. The respondents whom we interviewed live in an urbanised village, which combines the characteristics of a rural setup and a newer identification with the city. Our goal was to observe how translation occurs in a space thus characterised, especially with regard to a ritual rooted in the folkloric traditions of the state. Dev Uthan Ekadashi becomes a worthwhile object of translatological study because the women involved grapple with the challenges of the modern while performing the traditional.

METHODOLOGY

Even though we both belong to the same Haryanvi community and share similar cultural roots, we required access to the respondents—women aged 25 to 55—who spoke (the various dialects of) Haryanvi, Hindi, and English. This was facilitated by family members and friends, who thereby acted as gatekeepers. Although we conducted semi-structured interviews, what sets our study apart is our own role as active participant observers. Since translation was one of the commonly practiced and observed activities, we were motivated to study the phenomenon further.

We used the methodology of “thick description.” Introduced by Clifford Geertz in The Interpretation of Cultures (1973), it involves detailed contextualisation of any social action when performed in a cultural context; it emphasises studying the why, when, what, and where of an event (6). Our emic perspective helped us understand how women from our community interpret their actions and behaviour through the ritual. Most of our respondents straddle the rural and the urban—they belong to urban communities, but still actively participate in activities associated with the rural, especially the celebration of the rituals.

Our pilot study demonstrated that, rather than communicating in one language, our respondents relied on (different dialects of) Haryanvi, Hindi, English, or a mixture of all three. In addition, they translated between these languages. Among themselves, they spoke Haryanvi; however, they simultaneously translated for us into Hindi or English since we were not proficient in all the dialects of Haryanvi. In the following sections we illustrate these processes of intersemiotic translation, and demonstrate how, while interacting with us, the respondents enter a translation zone in which they negotiate meanings across Haryanvi, English, and Hindi.

DEV UTHAN EKADASHI

Dev Uthan Ekadashi (or Prabodhini Ekadashi, also known locally as Devotthan Ekadashi or simply Devthan), is celebrated around ten days after Diwali, the Hindu festival of lights. It falls on the eleventh lunar day (ekadashi) in Shukla Paksha (the waxing moon) of the month of Kartik, i.e. in October or November. It marks the awakening (prabodhini, -uthan, -than) of Lord Vishnu (Dev) from his four-month sleep and connotes the fresh beginnings of the Hindu wedding season. There are visual, aural, and performative elements to the festival: Haryanvi women gather, create images/illustrations representing Lord Vishnu, sing geets (folk songs), and perform several rituals.

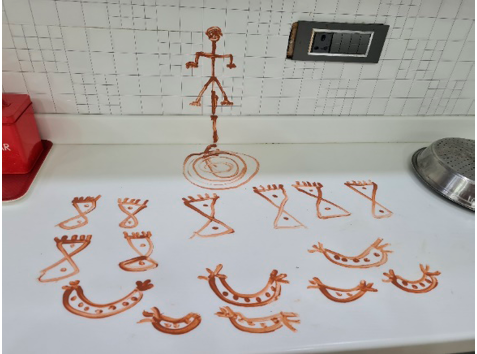

The ritual begins in the evening, when the women gather in groups to visit the neighbouring houses; however, the festival can also be celebrated individually. In the villages, the drawings were once prepared in the house’s cooking area, next to the chulha (brick-and-mud cooking stove, which used to be lighted with dung cakes and wood); these days, the drawings are made in the kitchen, on the counter-top and the wall, as can be seen in Fig. 1.

Courtesy of the authors.

The figure on the wall represents Lord Vishnu, and the markings on the kitchen countertop represent four pairs of feet. Following the tradition, Haryanvi women draw the feet of their family members, including their children, with geru (natural ochre). Our observations show that—especially in the cities—women also use geru on chart paper, paste the illustration on the kitchen wall, and then remove it for safekeeping. No other colours or materials are used.

Other symbols in the illustrations represent animals such as the cow (considered holy). During the ritual, women fast for the entire day, and create the drawings at night. They cook halwa (pudding of wheat flour or coarser granulated wheat) and cover it with a large deep platter, called a paraant. After the family dinner, just before going to sleep, the women sing and ceremoniously uncover the halwa, which signifies the awakening of Lord Vishnu. They also call out to the gods to wake up: “uth uth Dev, uth uth Dev,” or “utho mere Devta.” The ritual is important because, now that the Gods have been awakened, any marriage within the family can be solemnised; it thus marks an end to the four-month pause that begins the day after bhadaliya navmi (the ninth day of the waxing moon in Asaadha, in June or July), when the Gods are supposed to go into deep slumber.

Once the ritual is over, the women use the opportunity to converse, thus creating a feminine space for sharing personal anecdotes, stories, songs, ideas, and problems, and support one another by offering advice and opinions. However, we observed that the ritual is slowly being forgotten or confined to the margins of the culture and society; its contemporary function is not as pronounced as that of Ahoi Ashtami, which involves praying for the longevity of children. Moreover, in a modernising urban Haryana, fewer marriages are confined by caste and class; therefore, awakening the Gods to facilitate marriages is diminishing in significance, and the tradition may soon disappear.

USING ETHNOGRAPHY TO TRANSLATE GURUGRAM

The use of “thick description” meant that we concentrated on participant observation and focused group interviews. We immersed ourselves in watching our participants’ day-to-day routines, activities, and interactions, specifically cultural practices characteristic of Gurugram. As already mentioned above, we also conducted semi-structured interviews to collect and discuss their personal narratives, stories, and perspectives on the ritual.

Our major emphasis was on sensorial experiences: the sounds, smells, and sights. Our emic perspective, which enabled us to interpret our respondents’ behaviours, helped us create a cross-cultural study: dismissing homogeneous ethnocentric descriptions, we focused on the various meanings that rituals can exhibit. Ours was thus an intersemiotic translation of distinct non-linguistic resources.

For example, we posit that when our respondents conversed and walked together in the neighbourhood, wearing their traditional attire (clothes and jewellery), they created a space through which we were able to access various aspects of the city. In observing our respondents and producing field notes, we translated them and the city in a written semiotic order. Next, performing audio-visual documentation of the ritual against the larger backdrop of the city, we again translated our respondents and the city in a visual and oral semiotic representation system. Hence, through our ethnographic practice of interpretation, we offer an intersemiotic translation of the ritual as well as of the city by accessing and translating the social, cultural, emotional, and geographical spaces which the city allocates to the female respondents.

GURUGRAM AS A TRANSLATIONAL CITY AND A TRANSLATIONAL ZONE

Contemporary space has been examined as one that is constructed by overlapping and irregular structures (Appadurai 46); it is thus “not a smooth, homogeneous, neutral territory, but rather an extremely complex one due to all the differences it embraces, in terms of races, beliefs, ways of life and languages” (Vidal Claramonte 87). Given the diverse nature and the multiplicities that characterise any contemporary urban space, an individual embarks “on an undetermined journeying practice, having constantly to negotiate between home and abroad, native culture and adopted culture . . . between a here, a there, and an elsewhere” (Minh-ha 27). In her pathbreaking work, Sherry Simon introduces the concept of the translational city as follows:

There are no monolingual cities. The diversity of urban life always includes the encounter and exchange of languages . . . But urban languages do not simply coexist: they connect, they enter into networks. This means that cities are not only multilingual—they are translational. Translation tells which languages count, how they occupy the territory and how they participate in the discussions of the public sphere. (“The Translational City” 15)

In agreement with Simon, we believe that Gurugram establishes itself as a translational city. Its forms of translation are manifold. Since the city is home to various languages, such as Hindi, Haryanvi, and English, our respondents interact with one another in multiple languages. The ritual is obviously a performance, where—apart from translating for each other and for us—the women also perform through their bodies, thus occasioning intersemiotic translation.

In Eco-Translation, Michael Cronin demonstrates affinities between mapping the city and translation. He argues that there “are two potential ways to map a city”—one which “gives you the layout of the streets, the location of key transport hubs, sites of cultural and historical interests and major public utilities,” and another which is “based not on what routes people might take through a city but what routes they actually do” (110). Following the same approach, documenting the ritual and mapping Gurugram, we witnessed it—through our respondents—as a tapestry of cultures, languages, and experiences.

The responses to our questions were offered in Hindi and Haryanvi. A few younger respondents who had grown up in the city required assistance in understanding Haryanvi, and preferred to communicate in English and Hindi. What caught our attention was non-verbal behaviour, where a respondent entered the house of another, quickly sought out the Dev, and rushed to the image without uttering a single word. In fact, some of the respondents did not even greet one another, but merely looked at Lord Vishnu and left; as we discovered later, they wanted to ensure that their own Dev was superior in appearance. During the ritual, some respondents created their images in silence, and would browse through their homes for materials that would allow quick makeovers, while others turned to their fellow female respondents for validation of their creativity. These quick, heavy movements, devoid of utterance, exemplify the non-linguistic resources which allow for an intersemiotic translation of the ritual and the city.

Importantly, although English is no longer regarded as foreign or colonial, it is privileged in the linguistic and social hierarchy. In India, not everyone understands or communicates fluently in English. Furthermore, Hindi—despite being the dominant language in Northern India—does not serve as the lingua franca in states like Punjab and Haryana. Haryanvi, on the other hand, remains unrecognised as a language, owing to the absence of a linguistic script. As a result, it is Hindi rather than Haryanvi that Census records classify as the primary language spoken in Haryana. One of the goals of this paper, therefore, is to draw attention to the neglected Haryanvi “language.”

Thus, when translating between these languages, Haryanvi women effectively exhibit the multilingualism of such urban spaces, encouraging the participants to enter, thrive, and learn within a communication network. In spite of our familiarity with the language, we ourselves faced challenges in comprehending the several distinct (sub-)dialects of Haryanvi. Thus, as ethnographers participating in a communication network constructed by our respondents, we learned a new linguistic variant. Consequently, our respondents contributed to maintaining a multilingual urban Gurugram, where various languages coexist and participate in the public discourse.

A translational city, Gurugram can also be situated as a translation zone. The term emerged as analogous to Mary Louise Pratt’s notion of the “contact zone,” defined as a “social [space] where disparate cultures meet, clash, and grapple with each other, often in highly asymmetrical relations of domination and subordination—like colonialism, slavery, or their aftermaths as they are lived out across the globe today” (4). Emily Apter conceives of the zone as a “broad intellectual topography,” a territory of “critical engagement” that is not restricted by the boundary of a nation (5). We thus position Gurugram as a translation zone in Apter’s understanding of the term.

Gurugram’s identity as a translation zone is entrenched in its distinctive socio-cultural history. It began as a rural space where Haryanvi was predominantly spoken, and along with its urbanisation, it was gradually occupied by native and vernacular languages, like the sub-dialects of Haryanvi (e.g., Bagri), Punjabi, and Hindi. With the rapid expansion of the city at the turn of the 21st century, the influx of information technology companies, and the growth of the banking sector, Gurugram rapidly became a globalised, cosmopolitan city, where international languages such as English, French, or German came to be used by professionals and disseminated by educational institutions.

We also established through our ethnographic fieldwork that parts of the city with migrant populations bring their own languages to the mix, such as Gujarati, Punjabi, or Bhojpuri; other parts have a predominance of native population speaking their local languages or dialects, like Haryanvi, while still others are cosmopolitan centres using several international languages, such as French, English, or German. The intersections of these pockets constitute language contact zones. Hence, as a translation zone in a postcolonial environment, Gurugram “offers in conceptual terms a ‘third way’ between on the one hand an idea of the city as the co-existence of linguistic solitudes and on the other, the ‘melting pot’ paradigm of assimilation to dominant host languages” (Cronin, Translation and Identity 68). In the urban translation zone created by the Haryanvi women, “the focus is not on multiplicity but on interaction” (Simon, Cities in Translation 7). Rather than merely hosting a native population that speaks the local tongues, the city also has a cosmopolitan population with an array of international languages; hence, it is an urban space intersected by multiple social, cultural, and, of course, linguistic boundaries. Such a co-existence of a native and non-native population often gives rise to a one/other, us/them divide; however, multiple binaries of this kind co-exist in Gurugram. Our fieldwork demonstrates that the performance of Dev Uthan Ekadashi becomes another such contact zone.

Simon describes two imperatives of research into translating the city:

First, it responds to the need to focus on local practices and specific spatial contexts, breaking with the default reliance on national languages as end terms. In the city, translation takes place across a wide variety of idioms, regional variants and languages which are not necessarily “foreign” one to the other. They are physically proximate, share common references and in some cases share a common sense of entitlement to the city. Second, the city puts pressure on translation as a clearly bounded concept. Translation becomes a wide category of language exchange that includes translanguaging, multilingual artistic projects, . . . the shifts in individual identity that are forms of self-translation. (“The Translational City” 16).

As we have observed, these two aspects are in evidence during Dev Uthan Ekadashi in Gurugram. Firstly, it is a local female-centric socio-cultural tradition which, allocating prominence to the native languages, facilitates an environment in which Haryanvi and its variants often take precedence over Hindi as an official language. Performing the ritual, our respondents not only conversed, but joked and offered sexual innuendos in Haryanvi, and more specifically Bagri (the variant/dialect unique to Gurugram). As ethnographers, we acknowledge Bagri because of its positionality, marking a sort of prerogative to the city: Bagri exists because Gurugram exists.

Secondly, through the ritual, translation occurs as a process of linguistic exchange, in which some speak in Bagri, some in Hindi, while still others try to understand the ritual in the language of their convenience. As we argue in the following section, this playful exchange allows Haryanvi women to undergo a transformation of identity. They emerge as creators, performers, and translators—producing visual likenesses of Lord Vishnu; dancing, singing, and celebrating a day when they are not relegated to the status of homemakers; and, lastly, translating both the ritual and its languages.

HARYANVI WOMEN AS CULTURAL AGENTS/MEDIATORS

Examining a translational city, it is important to “listen” to it (Simon, Cities in Translation 1). Questioned about the relevance of the ritual, Anu Kataria, a postgraduate homemaker, responded: “Dev Uthan Ekadashi enables me to exhibit my creativity.” Another participant, Rekha Mehlawat, replied: “The ritual allows me to spend time with my friends, which is not possible otherwise as we all are usually busy in our day-to-day lives.” Asked for details, the respondent clarified: “We sit together once the ritual is over, talk, and catch up with each other.” Communicating across languages and dialects, Haryanvi women emerge as mediators in extant and emergent language networks, controlling communication and thus allowing the language to represent the city. Such translation becomes significant, because, as Simon reminds us,

the city does not exist outside of language, and access to its many worlds is a voyage across tongues. Translations bring into dialogue languages that are states of memory in the history of the city . . . and languages that are vehicles of memory in the present that convey the contemporaneous sometimes-competing narratives of long-standing inhabitants and newcomers alike. Translation points to the dissonance of city life, but also to the possibility of a generalized, public discourse, a space vital to urban citizenship—where the convergence of languages can be a source of new conversations. (Cities in Translation 18–19)

Such a reinterpretation of identity can be discerned in responses like that of Kiran Rana, a teacher by profession: “The ritual is a performance for us. It includes naach-gaana, aarti-puja, sajana-savarna” (“dance and song, prayers and offerings, dressing up”). Thus, Dev Uthan Ekadashi gives some women an opportunity to recreate their identity as “performers” distinct from their existing social, familial, and cultural identities: they are no longer marginalised domesticated beings, but appear as independent and empowered individuals. Another of our respondents, Sweety Sejwal, remarked: “On Dev Uthan Ekadashi, we no longer seek permission from the men of the house, but rather do as we wish.” Another jokingly added: “We are the housemen on that day, and they [men] are the women.”

Another significant aspect of the ritual is the traditional clothing and jewellery—prized possessions and an integral part of the Haryanvi women’s cultural heritage, in some cases an indication of their socio-economic position. Our fieldwork offered an opportunity to understand the role of these artefacts in establishing Haryanvi women as cultural agents and translators.

In the interviews, the Haryanvi women asserted that the jewellery and clothing worn while performing Dev Uthan Ekadashi give them a sense of belonging and empowerment, making them feel special and unique. One of the respondents, Manju Kataria, stated that “it looks very beautiful.” The ritual offers these women an opportunity to honour, cherish, and celebrate their cultural and social identity; as such, they take immense pride in the attendant jewellery or clothing. Since only married women have the privilege to own these, such cultural and material artefacts give them an opportunity to express themselves the way they want in an otherwise oppressive social setting—a patriarchal and misogynistic societal fabric, evident in Haryana’s skewed sex ratio, female foeticide, and honour killings. These appurtenances reflect the respondents’ feminine creativity and inclinations, their will to subvert societal hegemony and to resist the forces which marginalise them.

Some respondents who have relocated to (semi-)urban settings mention dressing up in their traditional Haryanvi attire to showcase their cultural identity; this allows them to forge a distinct identity within a cosmopolitan neighbourhood where women come from different walks of life and diverse cultural (and at times, national) backgrounds. Thus, during Dev Uthan Ekadashi, Haryanvi women use language as well as the ritual’s material and cultural appurtenances not only to promote their culture, but also to translate it for others. As a result, they function as cultural agents within a postcolonial space.

Through rituals like Dev Uthan Ekadashi, the women reconstruct their identities as independent individuals who, during this day, no longer require permission from their husbands/guardians/fathers(-in-law) to perform their motherly duties or mingle with other women in the neighbourhood. Such events allow them to situate themselves at the centre, to reclaim their spaces as individuals and as women, and—in the case of our respondents—as artists and translators.

Another respondent, Seema Hooda, asserted that at times she felt miserable because of an identity crisis. Simultaneously managing modernity and tradition, a Haryanvi urban woman often tries to justify her culture and traditional roots to her cosmopolitan friends and neighbourhood by establishing herself at the intersection of the two. Seema further explains that her interest in celebrating the ritual in—as she puts it—“the Haryanvi way” is justified when her friends do the same for their festivals. She confesses that her husband does not approve of her Haryanvi clothing and jewellery, which make her look “uncivilised and illiterate.” She therefore wears them mostly in his absence, but also when they attend social events, such as marriages or parties, together; those are the only occasions when her husband agrees to a social demonstration of their cultural and traditional roots.

Like Seema, Anu, Rekha, Kiran, and other respondents, we assert that the ritual is conducive for women, especially when they try to exhibit their cultural roots and exercise their choices as performers, translators, agents, or leaders of social change within this urban context, irrespective of their socio-economic or spatio-temporal positionality. Dev Uthan Ekadashi is thus community-driven when it transcends individual ritualistic contexts, and is constructed through social, cultural, and domestic forms of meaning-making. Rituals facilitate the shaping of identity through agents that appropriate or reshape values and ideals (Bell 82, 73), and Dev Uthan Ekadashi offers Haryanvi a space in which to resist patriarchy and misogynistic forces.

Thus, by enabling women’s creativity, Dev Uthan Ekadashi also allows them to challenge and mould socio-cultural values in a patriarchal society. Engaging in the ritual as “agents,” they may not necessarily condone, produce, or create the larger community-focused norms (Butler 171–80). As in the case of Sanjhi, another Haryanvi ritual which we documented elsewhere (Dhandhi and Sigroha), Dev Uthan Ekadashi concerns the “stylized repetition of acts” (Butler 179), e.g., performing the prayer, creating the Dev, and reciting folksongs. Hence, the rituals offer our respondents a space for “reproduction of and resistance to hegemonic images of female subjectivity” (Hancock 32, 137).

“[T]his is our performance,” one of the respondents, Anju Kataria, commented, and it consists of “dance, music, devotion, and grooming ourselves and our Dev.” She also asserted: “For one day we get enough rest as the men in the family help us in our domestic chores since we are occupied with worshipping Lord Vishnu.” Significantly, then, the ritual also becomes a space of subversion in which women (re)create and mould themselves as performers and visual artists. By appropriating these traditions to express themselves as autonomous and independent individuals, possessed of an agency to reflect and react, they subvert the submissive and hegemonic structures around them. Creating their own version of Lord Vishnu is an activity considerably different from their usual domestic responsibilities: they transcend their socially prescribed role of homemakers. Through music, dance, devotion, and creating distinct images of Lord Vishnu, the women reassert their independent identity as visual artists.

Discussing her drive to create Dev every year, Anu explains that she does this for herself, for the upcoming generations, and for her children. In contrast with the afore-cited respondent, helped by the male members of her family, she is supported by other women in her household chores. Building a foundation for a strong interpersonal relationship, she maintains a dual identity—a traditional homemaker and a visual artist.

Thus, the ritual offers women an alternate space for interpersonal relationships, often with the women living in the same house, which is otherwise impossible. Every year, women remerge to celebrate the festival, depending on their time constraints and amount of household work. Hence, for the marginalised Haryanvi women, this folkloric practice becomes the only medium of individual expression. Providing space for discussions on all matters and concerns, the ritual offers a socio-culturally accepted release of pent-up feelings.

Hence, through Dev Uthan Ekadashi, our respondents—who usually act as unpaid labourers within domestic spaces, possessing no form of cultural, social, or physical presence—produce a visual culture that expresses their individuality as well as offering fulfilment and sisterhood. Furthermore, this event creates an alternative socio-cultural space in both the public and the private domains, where the women are finally seen and heard, and able to exhibit their creativity. Thus, Dev Uthan Ekadashi allows our respondents a measure of subversion through female folklore.

CONCLUSION

Through a detailed analysis of the woman-centric ritual, we have demonstrated that Gurugram emerges as a translational city. Dev Uthan Ekadashi is here posited as an experience that empowers Haryanvi women, who act as moderators, translators, and performers, and who thus recreate their own identities. They become cultural agents within a postcolonial space where the ritual has survived despite spatio-temporal changes undergone both by the city and by the community. Performing the ritual, the Haryanvi women create a translation zone, where they actively translate their material culture (clothing and jewellery), but also interact in multiple languages and mediate between them. Hence, we assert that Gurugram is a translational site where a folkloric tradition is kept alive through women’s interactions within a multicultural and multilingual urban space.

Authors

Works Cited

“About District.” Gurugram District Official Website, Government of Haryana, https://gurugram.gov.in/about-district/, accessed 27 Mar. 2025.

Ahlawat, Neerja. “The Political Economy of Haryana’s Khaps.” Economic and Political Weekly, vol. 47, 2012, pp. 15–17.

Appadurai, Arjun. Modernity at Large: Cultural Dimensions of Globalization. U of Minnesota P, 1996.

Apter, Emily. The Translation Zone: A New Comparative Literature. Princeton UP, 2006. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400841219

Basalamah, Salah. “Translation Rights and the Philosophy of Translation: Remembering the Debts of the Original.” Translation—Reflections, Refractions, Transformations, edited by Paul St.-Pierre and Prafulla C. Kar, John Benjamins, 2007, pp. 117–32. https://doi.org/10.1075/btl.71.14bas

Bell, Catherine M. Ritual: Perspectives and Dimensions. Oxford UP, 1997. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780195110517.001.0001

Butler, Judith. Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. Routledge, 1990.

Buzelin, Hélène. “Translations ‘in the Making.’” Constructing a Sociology of Translation, edited by Michaela Wolf and Alexandra Fukari, John Benjamins, 2007, pp. 135–69. https://doi.org/10.1075/btl.74.11buz

“Census of India.” Census India, Haryana, Director of Census Operations, 2011, https://censusindia.gov.in/nada/index.php/catalog/24, accessed 27 Mar. 2025.

Cronin, Michael. Eco-Translation: Translation and Ecology in the Age of the Anthropocene. Routledge, 2017. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315689357

Cronin, Michael. Translation and Identity. Routledge, 2006. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203015698

“Demography.” Gurugram District Official Website, Government of Haryana, https://gurugram.gov.in/about-district/demography/, accessed 27 Mar. 2025.

Dhandhi, Muskan, and Suman Sigroha. “Translation for Women, Women for Translation: Experiential Translation in North India’s Sanjhi.” The Translation of Experience: Cultural Artefacts in Experiential Translation, edited by Ricarda Vidal and Madeleine Campbell, Routledge, 2025, pp. 55–72. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003462569-5

Geertz, Clifford. The Interpretation of Cultures: Selected Essays. Basic, 1973.

Hancock, Mary Elizabeth. Womanhood in the Making: Domestic Ritual and Public Culture in Urban South India. Westview, 1999.

Joseph, Eustace Alexander Acworth. The Customary Law of the Rohtak District. Printed at the “Civil and Military Gazette” Press by Samuel T. Weston, 1911.

Minh-ha, Trinh T. Elsewhere, Within Here: Immigration, Refugeeism and the Boundary Event. Routledge, 2011. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203847657

Murphy, Elizabeth, and Robert Dingwall. “The Ethics of Ethnography.” Handbook of Ethnography, edited by Paul Atkinson et al., Sage, 2001, pp. 339–51. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781848608337.n23

Pratt, Mary Louise. Imperial Eyes: Travel Writing and Transculturation. Routledge, 1992.

Rafael, Vicente L. Contracting Colonialism: Translation and Christian Conversion in Tagalog Society under Early Spanish Rule. Cornell UP, 1988.

Rafael, Vicente L. Translational Justice: Beyond the Limits of Language and Nation. Duke UP, 2023.

Simon, Sherry. Cities in Translation: Intersections of Language and Memory. Routledge, 2012.

Simon, Sherry. “The Translational City.” The Routledge Handbook of Translation and the City, edited by Tong King Lee, Routledge, 2021, pp. 15–25. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429436468-3

Vidal Claramonte, María Carmen África. “Translating Fear in Border Spaces. Antoni Muntadas´ on Translation: Fear/Miedo/Jauf.” CRATER, Arte e Historia, vol. 1, 2021, pp. 72–97. https://doi.org/10.12795/crater.2021.i01.05

Wolf, Michaela. “Introduction: The Emergence of a Sociology of Translation.” Constructing a Sociology of Translation, edited by Michaela Wolf and Alexandra Fukari, John Benjamins, 2007, pp. 1–36. https://doi.org/10.1075/btl.74

Wolf, Michaela, editor. Translating and Interpreting in Nazi Concentration Camps. Bloomsbury, 2016.