Community Centres as Sites of Translation: Placemaking in Edinburgh

Heriot-Watt University, Edinburgh

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5348-6281

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5348-6281

Heriot-Watt University, Edinburgh

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5791-0465

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5791-0465

Independent Scholar

https://orcid.org/0009-0008-4689-2426

https://orcid.org/0009-0008-4689-2426

Abstract

This article presents a research project comprising a series of community initiatives in Edinburgh, a city which displays a disproportionately English-heavy linguistic profile, despite the cosmopolitan influences of both migration and tourism. Our case study created sites that can be conceptualised as translation spaces, where the dominant direction of translation is challenged and critiqued, or even temporarily reversed to reclaim urban space. The research team collaborated with local libraries and community centres to establish several sites of translation. This paper focuses on one key site: a series of art workshops led by refugee artists. Drawing upon the concept of translation space from Translation Studies, we explicitly thematised the role of language(s) and language exchange in these microsites, so that language traffic and dynamics could be observed, discussed, and challenged. In this way, this article contributes to the study of translation space in two aspects. Firstly, it demonstrates how contested language spaces can be analysed through translation practices manifested in various material modes, including interpretations (or, oral translations) provided by participants for one another in art workshops, and intersemiotic translation, from feelings through languages to artwork. Secondly, the paper reflects on how creating such microsites of translation can contribute to resisting the dominant direction of translation in the city.

Keywords: translation space, counter-translations, materiality, intersemiotic translation, translation practices.

TRANSLATION AS SPATIAL, MATERIAL, AND LOCALISED PRACTICE

Cultural, ethnic, and linguistic diversity is a common feature of international cities shaped by migration and mobility. Languages are always competing for space in multilingual cities (Cronin 68). Translation, often likened to a metaphorical bridge that promotes intercultural communication, can also be manipulated to block communication, or to control how one language occupies the territory. As Simon comments, “[t]ranslation tells which languages count, how they occupy the territory and how they participate in the discussions of the public sphere” (Translational City 15). Reacting to this power imbalance, counter-translation—defined as the process of “reclaiming urban spaces through translation” (Marasligil 77)—has been championed as an effective community movement to critique this imposition, reverse the direction of translation, and return voices to minoritised and silenced languages. Against this backdrop, our action research project Edinburgh: A Translational City was carried out at various sites, including public libraries and community centres, in collaboration with community partners, in 2023–24. Its aim was to contribute to counter-translating cities both as an emerging research theme in translation studies (Simon, Translation Sites) and a community movement (Marasligil). This project draws on Marasligil’s broad conception of the city as “any space where there is human presence: through the architecture, the streets and the people” (78), with its emphasis on the interplay of people, practice, and space, rather than adhering to specific demographic or geographic parameters.

To investigate language practices in urban spaces, our study draws on the concept of the translational city, defined as “a space of heightened language awareness, where exchange is accelerated or blocked, facilitated or forced, questioned or critiqued” (Simon, “Space” 97). This theoretical framework entails two premises. Firstly, it highlights the driving forces behind the direction and the intensity of the circulation and flow of different languages, or language traffic (Simon, Translation Sites 5). The power structure in a society assigns the status of source language and target language in a city and pre-determines the direction of translation. For example, in a city with a requirement to present public signs in more than one official language, where the multilingual versions co-exist side by side, it is reasonable to expect one language to be produced first and then translated into other language versions. This means that one language is assigned the status of source language, and the other(s) become target languages, despite their officially equal status.

Language hierarchies are particularly relevant to newcomers to the city who have limited ability to speak the city’s dominant language. The languages of newcomers are often inaudible or invisible unless they are required by the host society (such as in legal cases when public service interpreters are provided). In Dangerous Multilingualism, Blommaert et al. have discussed the minoritising and endangering effects of state glottopolitics and language-ideological processes that are inherent in multilingual countries, cities, or communities. Such power differentials shape not only cities’ linguistic landscapes, but also their entire language ecologies, and they affect community relations and social cohesion. In this context, the city’s dominant language functions as the source text that newcomers need to translate into their own languages, often through self-translation or intersemiotic translation—broadly understood as translation across different semiotic resources. This can include translation between verbal and non-verbal signs, as well as among non-linguistic signs such as visual, acoustic, and spatial signs (O’Halloran, Tan, and Wignell 199). Building on Cronin’s argument that the migrant “condition” is that of “the translated being” (45), the same could be said of any linguistic minority, and thus communication of a minoritised self is in this sense always carried out through a process of translation.

The co-dependence of languages and space, and the practice of intersemiotic translation led to the second premise of the translation city: namely, translation as an embodied experience, anchored and enacted by a city. This shift from a linguistic to a spatial focus in translation studies not only moves the emphasis from intangible “source language space” to tangible physical settings in which translation activities take place; it also moves away from focusing on source text and targets text languages as abstract linguistic systems. Instead, this approach emphasises observable doings in everyday life in which people draw on communicative and material resources to construct their localised practices. This localised and material view of languages is informed by several approaches in applied linguistics and social sciences, such as research into linguistic landscapes (Shohamy, Rafael, and Barni), semiotic landscapes (Jaworski and Thurlow), and metrolingualism (Pennycook and Otsuji).

Studies on translation and language practices in cities often use terms including spaces, places, sites, and landscapes to refer to the geographical areas or locations which they examine. While these terms may sometimes be seen as synonyms, they carry distinct meanings that warrant clarification. Broadly speaking, space is a more neutral and abstract geographical area. In human geography, it is often seen as the raw material that has the potential to turn into place (Tuan): placemaking occurs when we “invest meaning in a portion of space and then become attached to it in some way” (Creswell 16).

A distinction can also be made between space and sites—the latter typically referring to specific geographical locations used or designed for particular purposes or functions. In her monograph Translation Sites, Simon guides readers through various locations imbued with distinct functions and meanings, such as markets, monuments, museums, bridges, towers, and hotels. Finally, the term (linguistic) landscapes is used in research emphasising the visual inscriptions in city space, such as multilingual street signs (Jaworski and Thurlow 2).

Against this backdrop, a translational city approach also takes a new perspective towards the translator’s role. Based on the linguistic definition of translation, only professional linguists who had mastered at least two languages were previously considered to be competent translators. However, if we resort to the idea of language as observable, localised, strategic everyday doings (Pennycook), it becomes apparent that translation is an everyday activity, and people who live in this city need to perform the role of translators—regardless of the languages that they speak, and their level of language proficiency. Translation in these cases “does not refer only to texts but is used broadly in the sense of conveying meaning between and across languages” (Strani 30).

Against this theoretical background, with new development in looking at translation and language practices, and with a view of community members as everyday translators, this project, Edinburgh: A Translational City, involved a collaboration with several community centres in Edinburgh to create a series of workshops as sites of translation, where language awareness is heightened (Simon, “Space” 97) and the traffic of languages in all directions, drawing from a range of semiotic resources, is encouraged. In this paper we evaluate one series of workshops and address three questions: (1) How are translation practices adopted by community members in the created sites of translation? (2) How do these translation practices contribute to their placemaking? (3) How does translation space as a method function as counter-translation that critiques the established structure in a city?

CREATING TRANSLATION SPACE AS RESEARCH METHOD

To explore how the concept of translation space can be instrumental both as a theoretical concept and as a research method, this section draws on three interrelated subjects to further establish a link between placemaking, the counter-translation act, and the creative workshops.

PLACEMAKING AND LANGUAGE

As defined earlier, when we assign meaning to a space and form an emotional attachment to it, space becomes place. This process of creating a place can be literally understood as placemaking. This geographical understanding of human attachment to a place is reflected in metaphorical language uses such as the phrases “to place someone” and “to know one’s place” (Jaworski and Thurlow 6). Courage emphasises that placemaking should not be confused with urban planning or studies on built environment, which primarily focus on city-wide infrastructure such as buildings and transportation systems (3). In contrast, the essence of placemaking lies in human activities and community. Notably, socially engaged art practice has emerged as both a central theme and a key tool employed in the practice of placemaking (ibid.).

Placemaking is the iterative, affective process whereby individuals, in their social, political, and material interactions with physical space, come to understand and experience a particular geographical location not as an indeterminate space, but as a meaningful place (Duff; Pierce, Martin, and Murphy; Ralph and Staeheli). Creswell contends that place is “the raw material for the creative production of identity” (71). Placemaking is therefore fundamentally relational (Pierce, Martin, and Murphy): the meaning of a place, and the potential attachment to it, are not inherent in the physical characteristics of a location but are rather assembled over time by the individuals who inhabit and engage with that space. The foundational premise of this project is that a sense of belonging in place is essential for newcomers to truly establish a home in a new country (Antonsich; Lewicka). Processes of homemaking and placemaking unfold through the everyday practices, including language practices, of individuals within this geographical location. For migrants who do not share the same language as the host country, engaging in bilingual or multilingual practices becomes paramount in their daily routines, often serving as both a crucial element in placemaking and as a barrier to developing a sense of place (see Collins and Slembrouck; Nic Craith).

(COUNTER) TRANSLATION SPACE

While translation is a part of our everyday lives, because of the status associated with each language and its users, translations in some directions or involving some languages are not always observable in the public space. For example, several libraries in Edinburgh organise storytelling sessions in Gaelic, Greek, Polish, or Spanish for pre-school children and their carers. While the sessions are conducted in languages other than English, they are usually brief (around 30 minutes), infrequent (once a week or even a month), and offered in only a few libraries. Therefore, these activities may go unnoticed by those not specifically looking for this information. For researchers, this means that although translations performed by certain groups of language users can be easily observed in public space, others “come to light only through determined micro-cosmopolitan excavation” (Cronin and Simon 120). As in the above example of libraries, we need to check each library’s information page individually or obtain information from someone within the language community. Although the previous quote referred to cities which had undergone different historical language regimes and where previously spoken languages might therefore only be found buried in old buildings or historical records, the same argument is valid for the situation which interests us: that is, less powerful languages are silenced by more powerful ones in a cosmopolitan city (see Blommaert et al.; Piller).

One notable project that actively challenges the power imbalance in translation space is Marasligil’s City in Translation. In this project, Marasligil describes her role of translator as a “flâneuse, the female equivalent of flâneur” (79, emphasis in the original), as someone who walks, observes, and wanders through the material traces of language created by city dwellers across the urban space (ibid.), such as graffiti, shop signs, and public notices. Her workshops involve participants walking through the city space, photographing “multilingual self-expressions” in different languages and modes of presentation in the public space, and then writing about or discussing this space. Translation is realised in the first encounter with familiar or unfamiliar languages, attempting to interpret the meaning of these linguistic signs in the spatial context, and following creative works (poems, story writings) developed from the visual. Through these determined efforts to foreground languages in space, the project aims at “reclaiming urban spaces through translation” (77).

Similar projects have been carried out to establish a link between immigrants, languages, and space, although the term “translation space” may not be used. “Translanguaging space” is a term that has been used by some (e.g., Bradley et al.; Yoon-Ramirez), and others refer to “multilingual space” (Frimberger). Such terms focus less on the direction and intensity of language traffic when compared to translation space, but these projects share the aim of heightening language awareness. For instance, they provide explicit guidelines for research participants to look for different languages in the streets, or to examine which languages they encounter or use in their lives, and in what ways, highlighting the multidirectional flow of language in urban cities.

CREATING SPACE THROUGH CREATIVE METHODS

Many projects addressing translation cities adopt non-verbal creative methods. Ironically, this is because of translation problems. In a project that involves participants from diverse linguistic backgrounds, one cannot always expect to find a common language that is equally accessible to all, or that everyone is comfortable using. A community project can target participants from a single linguistic background, which the researcher may share, or an interpreter can be hired for the group. Alternatively, all participants must communicate in the host country’s dominant language. These kinds of arrangements, while proven to generate useful data (e.g., Ciribuco; Zhu, Li, and Jankowicz-Pytel), run the risk of, once again, overlooking the translation practices of some groups. That is why in this study on translation practices, we consider translation as a meaning-making approach and adopt creative workshops as methods to allow translation practices to be observed and analysed through a combination of verbal, visual, and other modes. This way, we ensure that those who speak little or none of the language of the researcher or the host country can still fully participate. Regardless of language proficiency, participants may feel too self-conscious to express deep feelings verbally, but may find communication easier when it is mediated through material processes such as choosing craft materials or colours. Brice points out that drawing, for instance, is not just image on a flat paper, but a process that can “open up further spaces of encounter, at bodily, sensory, cultural and political registers” (144–45).

For this project, multiple “sites of translation” were established across Edinburgh from 2023 to 2024, in collaboration with various community hubs including city libraries, community centres, and governmental organisations. A series of activities were organised, including a translated book exhibition, conversations with a literary translator, potluck focus groups, as well as art and craft workshops and exhibitions. This paper’s focus is on one specific activity as a case study: participatory art workshops.

THE ART WORKSHOPS

Ten two-hour art workshops were jointly organised with the Edinburgh and Lothians Regional Equality Council (ELREC). The activities included drawing, clay work, and collage. ELREC has long served as a vital hub for immigrants and refugees in the city of Edinburgh, offering regular classes such as ESOL, knitting, and cooking workshops. The workshops started with the organisers introducing ELREC, the research project, and the tools and materials available. Consent forms were obtained from the participants before the activities began. Participants then freely moved around the space, selected materials, and took refreshments. The dynamics among participants varied across workshops, influenced by factors such as linguistic backgrounds (i.e. whether they had shared languages) and their dispositions, with some participants engaging in lively discussions, while others focused on their artworks. After completing them, participants were invited to provide written descriptions of their drawings, encouraged to write in English and/or their other languages. Several participants who did not provide captions or were unable to do so during the workshop later submitted their captions to us via the group chat. Subsequently, the artworks, accompanied by their captions, were displayed in a local library as an exhibition.

LANGUAGE TRAFFIC AND AWARENESS

The primary question of interest revolves around the extent to which language awareness was heightened within the sites of translation that we established. Despite English serving as the main language of the workshop, used by the researchers in recruitment advertisements and in introducing the activities, multidirectional language traffic was observed among participants representing over 20 different languages. Individuals engaged in translanguaging, a communicative practice in which people use a range of linguistic and non-linguistic resources to communicate with one another. The workshop participants thus actively created a “translanguaging space” (Blackledge and Creese 250), where their distinct personasl, cultural, and linguistic backgrounds were brought into encounter. Participants with shared languages naturally formed groups, and sometimes these became heterogenous groupings of participants with geographically or culturally proximate languages. For example, Cantonese and Mandarin speakers with shared written characters, Indian participants conversing in various national languages, and Arabic speakers from different countries came together in clusters. Despite occasional linguistic misunderstandings and moments of guesswork, their shared cultural background helped to bridge the gaps—whether through humming a familiar song or showing a picture of their favourite food on a phone.

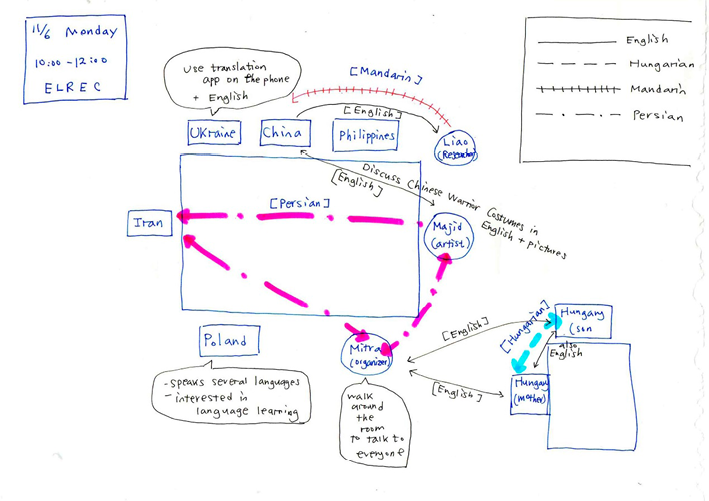

Liao’s sketch of language traffic in one workshop (Fig. 1) illustrates how participants used different languages in the session. This drawing, created as part of the researcher’s fieldnotes during the workshop, can also be viewed as a mapping of translation space—a cartographic translation of the researcher’s embodied experience of moving between participants, listening to their conversations, and looking at their art creations. All of these workshop activities were translated by the researcher into a spatial configuration of lines, dots, arrows, colours, and words.

In this workshop, seated at the main table alongside the two Persian-speaking event facilitators were five participants originally from China, Ukraine, the Philippines, Iran, and Poland, respectively. In addition, a mother and son from Hungary occupied another small table. English predominated at the main table, although the three Iranian participants also conversed in Persian among themselves. The Ukrainian participant, with limited English proficiency, was less engaged in the conversation but made attempts to explain her drawing—the national flower of Ukraine—with the help of a translation app on her phone and assisted her communication with gestures and facial expressions. The researcher (Liao) initially attempted to communicate with the participant from China in Mandarin. However, the participant responded in English, prompting the researcher to shift to English as she sensed that this was the participant’s preferred language in the workshop. The Polish participant demonstrated fluency in English and expressed interest in learning other languages. Similarly, the Hungarian boy shared his interest in learning Japanese with the group.

At the small table shared by the Hungarian mother and son, a mix of Hungarian and English was spoken, though the boy said that he preferred to speak in English. His bilingual upbringing and passion for learning new languages was reflected in the caption which he provided for his drawing of a sword: “Sometimes I choose to pull the sword out, sometimes I choose to leave it there and sometimes it’s hard to pull it out. I want to learn more languages, so it’ll be easier to pull out the sword. I chose the sword (as metaphor) because it represents power and knowing a language gives us power.” Both his drawing and writing strongly convey his view of speaking multiple languages as a source of strength and his “agentive capacity” (Miller) as a language learner—he felt empowered by his ability to choose which language to use in different situations.

A clear indication of heightened language awareness observed in the workshop was the natural emergence of language as a common icebreaker among participants. While group conversations were not deliberately initiated or guided, it was quite common for discussions about languages to naturally spark interaction among participants. When new participants met, they often engaged in conversations about their language backgrounds, discussing the number of languages which they speak, or how they learned languages, for example. The discussion also often revolved around the comparison of languages, including the identification of false friends. For instance, the Persian, Hindi, Urdu, and Arabic participants talked about halwa as a common food name in their languages, but through their discussions they discovered that the methods of making this food and its appearance in their cultures were different.

INTERSEMIOTIC TRANSLATION: FEELINGS OF THE LANGUAGES OF EDINBURGH

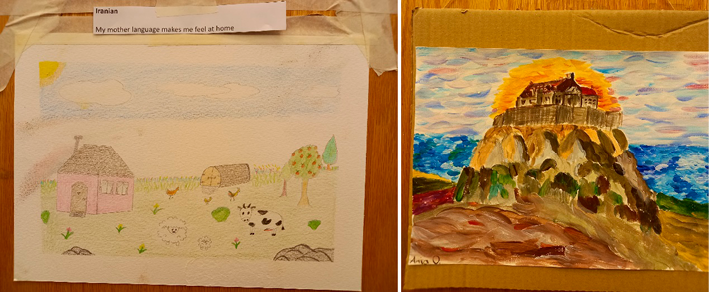

The workshops demonstrated a range of themes in art creation, reflecting participants’ positive feelings towards their first languages,[1] as well as their frustration and struggles with English as the new language. Their positive feelings toward their first languages were often expressed through natural themes like the sun, trees, and mountains, as well as national symbols such as flags and national flowers. In addition, cultural icons also appeared, including the Nile River in a Sudanese drawing, Mount Fuji in a Japanese drawing, and a simple geometric symmetrical diagram in an Iranian drawing. A series of drawings by Majid, the lead artist from the workshop, particularly reflects the social, religious, and mythical themes in Persian culture. Some participants also integrated their first languages into the visual expression—for instance, a participant from Hong Kong often added calligraphy beside her paintings. Jaworski and Crispin argue that visual symbols help “transpose images of ‘home’ into the mediated and mediatized spaces in which [migrants] live their diasporic subjectivities” (8).

The imagery of home is a common theme in many participants’ creations, as exemplified in Fig. 2 (left). This painting by an Iranian participant uses pencil with soft colours to portray a simple farmhouse, surrounded by trees, flowers, and animals. The caption provided by the participant reads: “My mother language makes me feel at home.” The “mother language” as referred to in this label is the key to making you feel at “home”—a term that is argued to be the metaphor of a general understanding of place (Creswell 39). Being at home also evokes a sense of security, and several participants also drew castles as a symbol of security and protection in relation to using their first languages. In Fig. 2 (right), a Polish participant wrote: “My language is like an untouchable castle built on strong rocks.”

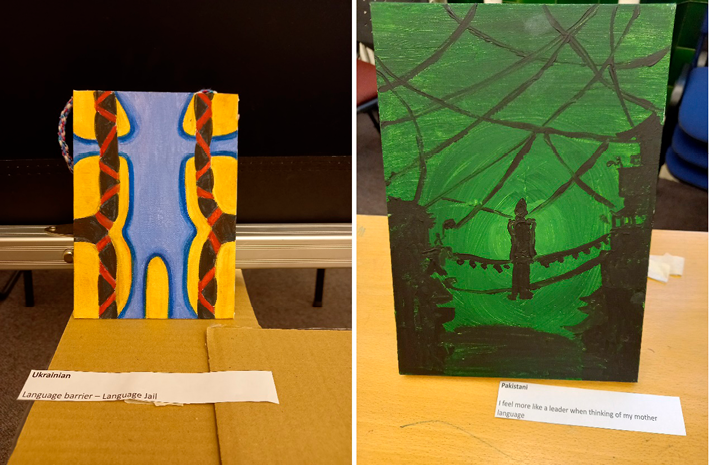

On the other hand, feelings towards the new languages are often expressed in much darker tones. Fig. 3 (left) is a painting by a Ukrainian participant with very limited command of English. Unlike the soft colour and concrete references to the objects in Fig. 2, this drawing takes a more abstract approach, using only shapes and lines, and vibrant, contrasting colours. The caption is simple, “Language barrier—language jail.” This is a deeply provocative creation that communicates linguistic isolation: the immense struggle with the language and the new life that needs to be mediated through it. The other painting by a participant from Pakistan (Fig. 3, right) is also abstract, featuring a black silhouette that appears to be suspended and locked by several chains in the centre, against a dark green background. The caption states: “I feel more like a leader when thinking of [in] my mother language.” The writing contrasts with the confined figure in the drawing. Both paintings emphasise a sense of helplessness and lack of control. As noted by Blommaert, Creve, and Willaert, immigrants who are fluent in their first language—or languages—often feel language-less and are perceived as illiterate (49) when transitioning from one space to another. In this context, Miller argues that “space is thus neither neutral nor empty” (445).

As discussed earlier, these feelings towards languages may not be easily expressed in words, but they are vividly and creatively communicated through visual modes. This process of translating internal feelings into tangible artwork is illustrated through one Czech-speaking participant, who shared with us how engaging in creative clay work for two hours provided her with a deeper reflection on her experience as a foreigner living in Edinburgh. Initially, she did not have a clear idea about what she wanted to express, but through the embodied experience of using her hands to engage with various materials, her aims became clear. Her experience echoes the argument that drawing is not just “capturing a moment frozen in time,” but “an embodied physical act influenced by the artist’s emotions, perceptions and experiences” (Kearns et al. 116).

PLACEMAKING: LINKING THE PAST TO THE PRESENT

Imagery of home and visual symbols such as non-Latin scripts, national flags, and emblems not only reflect immigrants’ nostalgia towards the past; bringing these symbols into new spaces also allows them “to claim these urban spaces as ‘their own’ —to make the foreign and distant, familiar and present” (Jaworski and Crispin 8). The creative artwork provides us with a rich insight into how participants anchor themselves in this new place through their past. A Cantonese-speaking participant simply drew two tomatoes and wrote that these can be used to make either tomato-and-egg stir-fry or borscht soup. This simple drawing demonstrates how food items and foodways are “vital aspect[s] of material culture for migrants and asylum seekers as [they] can help maintain social and cultural links to their home country and preserve cultural memory” (Todorova 89), that is, linking the past and present.

In Fig. 4, a second-generation British-born participant from an Indian family brought a Hindi textbook from her childhood. She then sketched a bicycle in a garden, decorated with some Hindi characters. In this drawing, the bicycle serves as a means of transportation, carrying the past (represented by the Hindi characters) into the present (her home garden). The Hindi characters in this picture are simultaneously verbal, visual, and affective. As she painted during the workshop, the participant shared amusing stories with us about the challenges she faced while learning characters as a girl, bringing her childhood emotions into the translation space.

The past may also be linked to the present through a historical connection between the home country and the UK, as demonstrated by the creations of several participants from Hong Kong. In one session, we observed how a participant connected the past with the present through football, specifically, his longstanding support for Liverpool FC, dating back to his time in Hong Kong. His caption reads: “As a Hongkonger who was born in the 1960s, Liverpool Club naturally became my favourite team. Liverpool used to be the team that had collected all major trophies in the 1980s & 1990s. . . . For us, Liverpool has a strong link with Hong Kong people.” Football is the vital bridge that connects his past to the present (a similar discussion on how football functions as a complex semiotic system in translating the daily lives of asylum seekers can also be found in Ciribuco). It is noteworthy that this participant, who had received a British education and was immersed in British culture from childhood in Hong Kong, had a higher level of English than other Hong Kong participants attending the workshops regularly. As a result, he served as an interpreter and “spokesperson” for the group.

Overall, the twenty hours of workshops involved more than 50 participants from a range of linguistic backgrounds, engaging in multidirectional language exchanges within the workshop spaces. As a form of intersemiotic translation, their art creations give us insights into their linguistic and placemaking practices.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

The Edinburgh: A Translational City project contributed to our understanding of translation and counter-translational practices in an agonistic space where languages compete to be heard. To answer the first research question on how translation practices are adopted by community members in the created sites of translation, a range of translation practices, in its broadest sense, were observed. The ELREC participants identified their common languages as lingua franca, and some interpreted from and into English for other participants. Communication was also facilitated through mobile translation apps, drawings, and body gestures. Creative examples of intersemiotic translation were noted, including visual artworks that express feelings for languages; food and sports that connect immigrants’ past and present; and material objects like childhood language textbooks that visualise competing languages in the translation space.

The second question was how translation practices contributed to placemaking. Creating boundaries is a central aspect of placemaking, and that was evident in the art workshop (Fig. 1), when the researcher (Liao) attempted to speak Mandarin with one participant, but they insisted on speaking English. For many workshop participants, placemaking implied creating a protected and bounded territory of safe language practices, linguistic freedom, and justice (Van Parijs). Art workshop participants drew castles to illustrate the safety and protection of their first languages, for example. A castle is also a fortress; a military or defence symbol, implying that an enemy threatens those inside it. These participants’ drawings, which strongly depict their first language as home or as a protected space, are also an example of setting linguistically constituted boundaries to counter the hegemony of dominant languages and their spaces. By constructing their own, personal linguistic boundaries, which do not conform to the expectations of the host society, the participants establish a space of translation which becomes a place of dynamic, non-conforming, and reclaimed language use.

Affect is another key component of placemaking: bodies are affected by place, but the affective states encountered in a particular place also contribute to how this is conceptualised and experienced in future (Duff). The artworks created within the ELREC project demonstrate that participants experienced their engagement with translation practices as deeply affective. By actively negotiating practices of translation, participants negotiated their affective experience of the translation space, establishing the horizon of possibilities there: and although those possibilities include the sense of being in “language jail” and bound by chains, they also involve connection, creativity, and resistance, as exemplified by the Hungarian boy’s sword, which he can choose to use to defend himself. Finally, to answer the third research question on how translation space functions as counter-translation that critiques the established structure in a city, the art workshops created translation spaces that encouraged participants to explore alternative ways of engaging with, and counter-translating, the multilingual city. Rather than simply translating the city from English into their own languages, participants from diverse linguistic backgrounds were invited to use creative methods to break language barriers—through drawing, feeling, and imagining. The various art and craft activities in ELREC, for example, supported participants to incorporate these experiences into their ongoing processes of affective placemaking. This study therefore contributes a multimodal perspective that is often overlooked in literature on translation spaces which relies predominantly on verbal methods.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We extend our deepest gratitude to Mitra Rostami and Tianyue Liu from the Edinburgh and Lothians Regional Equality Council, and Majid Mokhberi, the lead artist for the workshops. This project was made possible through the joint funding of the Royal Society of Edinburgh and Heriot-Watt University.

Authors

Works Cited

Antonsich, Marco. “Searching for Belonging—An Analytical Framework.” Geography Compass, vol. 4, no. 6, 2010, pp. 644–59. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-8198.2009.00317.x

Blackledge, Adrian, and Angela Creese. “Translanguaging and the Body.” International Journal of Multilingualism, vol. 14, no. 3, 2017, pp. 250–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790718.2017.1315809

Blommaert, Jan, Lies Creve, and Evita Willaert. “On Being Declared Illiterate: Language-ideological Disqualification in Dutch Classes for Immigrants in Belgium.” Language and Communication, vol. 26, no. 1, 2006, pp. 34–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.langcom.2005.03.004

Blommaert, Jan, et al., editors. Dangerous Multilingualism. Palgrave Macmillan, 2012. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137283566

Bradley, Jessica, et al. “Translanguaging Space and Creative Activity.” Language and Intercultural Communication, vol. 18, no. 1, 2018, pp. 54–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/14708477.2017.1401120

Brice, Sage. “Situating Skill: Contemporary Observational Drawing as a Spatial Method in Geographical Research.” Cultural Geographies, vol. 25, no. 1, 2017, pp. 135–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474474017702513

Ciribuco, Andrea. “Translating the Village: Translation as Part of the Everyday Lives of Asylum Seekers in Italy.” Translation Spaces, vol. 9, no. 2, 2020, pp. 179–201. https://doi.org/10.1075/ts.20002.cir

Collins, James, and Stef Slembrouck. “Multilingualism and Diasporic Populations: Spatializing Practices, Institutional Processes, and Social Hierarchies.” Language and Communication, vol. 25, no. 3, 2005, pp. 189–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.langcom.2005.03.006

Courage, Cara. “Introduction: What Really Matters: Moving Placemaking into a New Epoch.” The Routledge Handbook of Placemaking, edited by Cara Courage et al., Routledge, 2021, pp. 1–8. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429270482-1

Cresswell, Tim. Place: An Introduction. Wiley Blackwell, 2015.

Cronin, Michael. Translation and Identity. Routledge, 2006. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203015698

Cronin, Michael, and Sherry Simon “Introduction: The City as Translation Zone.” Translation Studies, vol. 7, no. 2, 2014, pp. 119–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/14781700.2014.897641

Duff, Cameron. “On the Role of Affect and Practice in the Production of Place.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, vol. 28, no. 5, 2010, pp. 881–95. https://doi.org/10.1068/d16209

Frimberger, Katja. “Towards a Well-being Focused Language Pedagogy: Enabling Arts-based, Multilingual Learning Spaces for Young People with Refugee Backgrounds.” Pedagogy, Culture & Society, vol. 24, no. 2, 2016, pp. 285–99. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681366.2016.1155639

Jaworski, Adam, and Crispin Thurlow, editors. “Introducing Semiotic Landscapes.” Semiotic Landscape: Language, Image, Space, edited by Adam Jaworski and Crispin Thurlow, Bloomsbury, 2010, pp. 1–40.

Kearns, Robin, et al. “Drawing and Graffiti-based Approaches.” Creative Methods for Human Geographers, edited by Nadia Von Benzon et al., Sage, 2021, pp. 113–25. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781529739152.n9

Lewicka, Maria. “On the Varieties of People’s Relationships with Places: Hummon’s Typology Revisited.” Environment and Behavior, vol. 43, no. 5, 2011, pp. 676–709. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916510364917

Marasligil, Canan. “Reclaiming Urban Spaces through Translation: A Practitioner’s Account.” The Routledge Handbook of Translation and the City, edited by Tong King Lee, Routledge, 2021, pp. 77–94. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429436468-7

Miller, Elisabeth R. “Agency, Language Learning, and Multilingual Spaces.” Multilingua, vol. 31, no. 4, 2012, pp. 441–68. https://doi.org/10.1515/mult-2012-0020

Nic Craith, Mairéad. Narratives of Place, Belonging and Language: An Intercultural Perspective. Palgrave, 2012. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230355514

O’Halloran, Kay L., Sabine Tan, and Peter Wignell. “Intersemiotic Translation as Resemiotisation: A Multimodal Perspective.” Signata, vol. 7, 2016, pp. 199–229. https://doi.org/10.4000/signata.1223

O’Rourke, Bernadette, and Joan Pujolar. “From Native Speakers to ‘New Speakers’—Problematizing Nativeness in Language Revitalization Contexts.” Histoire Épistémologie Langage, vol. 35, no. 2, 2013, pp. 47–67.

Pennycook, Alastair. Language as a Local Practice. Routledge, 2010. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203846223

Pennycook, Alastair, and Emi Otsuji. Metrolingualism: Language in the City. Routledge, 2015. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315724225

Pierce, Joseph, Deborah G. Martin, and James T. Murphy. “Relational Place‐making: The Networked Politics of Place.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, vol. 36, no. 1, 2011, pp. 54–70. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-5661.2010.00411.x

Piller, Ingrid. “Multilingualism and Social Exclusion.” The Routledge Handbook of Multilingualism, edited by Marilyn Martin-Jones, Adrian Blackledge, and Angela Creese, Routledge, 2012, pp. 281–96.

Ralph, David, and Lynn A. Staeheli. “Home and Migration: Mobilities, Belongings and Identities.” Geography Compass, vol. 5, no. 7, 2011, pp. 517–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-8198.2011.00434.x

Shohamy, Elana Goldberg, Eliezer Ben Rafael, and Monica Barni, editors. Linguistic Landscape in the City. Multilingual Matters, 2010. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781847692993

Simon, Sherry. “Space.” The Routledge Handbook of Translation and Culture, edited by Sue-Ann Harding and Ovidi Carbonell Cortés, Routledge, 2018, pp. 97–111. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315670898-6

Simon, Sherry. “The Translational City.” The Routledge Handbook of Translation and the City, edited by Tong King Lee, Routledge, 2021, pp. 15–25. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429436468-3

Simon, Sherry. Translation Sites: A Field Guide. Routledge. 2019. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315311098

Strani, Katerina. “Multilingualism in/and Politics Revisited: The State of the Art.” Multilingualism and Politics: Revisiting Multilingual Citizenship, edited by Katerina Strani, Palgrave, 2020, pp. 17–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-40701-8_2

Todorova, Marija. “Translating Refugee Culinary Cultures: Hong Kong’s Narratives of Integration.” Translation and Interpreting Studies, vol. 17, no. 1, 2022, pp. 88–110. https://doi.org/10.1075/tis.21019.tod

Tuan, Yi-Fu. Space and Place: The Perspective of Experience. Arnold. 1977.

Van Parijs, Philippe. “Linguistic Justice and the Territorial Imperative.” Critical Review of International Social and Political Philosophy, vol. 13, no. 1, 2010, 181–202. https://doi.org/10.1080/13698230903326323

Yoon-Ramirez, Injeong. “Inter-weave: Creating a Translanguaging Space through Community Art.” Multicultural Perspectives, vol. 23, no. 1, 2021, 23–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/15210960.2021.1877544

Zhu, Hua, Wei Li, and Daria Jankowicz-Pytel. “Translanguaging and Embodied Teaching and Learning: Lessons from a Multilingual Karate Club in London.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, vol. 23, no. 1, 2019, pp. 65–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2019.1599811

Footnotes

- 1 The term “first languages” here refers to the languages predominantly used by the participants prior to their relocation to the UK. In the literature they have also been referred to as mother tongues or native languages, but there has been ongoing debate surrounding power dynamics among language users associated with these terms (see O’Rourke and Pujolar). Alternatively, in the context of translation space, they can also be understood as the source languages of these participants.