https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5458-7842

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5458-7842

University of Lodz https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5458-7842

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5458-7842

Bringing together insights originating in law studies and art analysis, this article approaches the work of the US-based Syrian artist Lara Haddad through the figuration of “interior frontiers,” exposing how both “interior bonds” and “internal borders” tended to shape legal regulations introduced in the US in the aftermath of 9/11 for the purpose of conducting “the global war on terror.” Referring to the concept of “plasticity,” the article examines the intimate (dis)identifications experienced by the artist in the context of the politically saturated cultural discourses on violence which emerged from the post-9/11 spatialities of (inter)national law. The article argues that politically engaged art offers a means to affectively connect with the personal ways of coping with the persistent visceral presence of structural violence, shedding light on how political protocols and cultural representations impinge upon the individual experiences of many Muslims residing inside and outside the US territory. Opening established meanings to new interpretations, such art contributes to the process of revising dominant oppressive significations, creating room for critical contestation and increased transcultural understanding.

Keywords: Syrian refugees in the US, interior frontiers, torture, plasticity, artistic self-portraits, (dis)identification, Lara Haddad

Situated at the intersection of law and art studies, this article examines the work of Lara Haddad, an artist who—due to the eruption of war in Syria, her country of origin—relocated to the US in 2012.[1] My reading of the selected prints from her project A Question of History (2015–16)[2] draws on the figuration of “interior frontiers” (Balibar, La crainte des masses; Masses, Classes, Ideas; Stoler), indicating how both “interior bonds” and “internal borders” sit at the roots of several legal regulations introduced in the context of the “global war on terror”; it also employs the concept of “plasticity” (Malabou, The New Wounded) to reveal how “interior frontiers” are intimately negotiated and engaged with by the artist.

The article argues that politically informed art such as Haddad’s can effectively convey the complex extremities constituting the everyday experiences of many Muslims (residing inside and outside the US territory), and emerged in the post-9/11 context from the complicated spatialities of (inter)national law. Produced shortly before the official nomination of Donald Trump as a presidential candidate, yet within the political mood of xenophobic and nationalist discourses that eventually brought him into office, Haddad’s work helps us to engage with an expanded understanding of the term “extreme” as applied to the intimate, ambivalent experience of (non)belonging in a country which criminalizes Muslim refugees, yet—as in Haddad’s particular case—allows for survival and temporary stabilization, away from the ongoing ravages of war. In my view, in such a situation, artistic practice becomes for Haddad a space of negotiating the extremities of living under forms of duress that tend to go unregistered, while providing her with a means of coping with the persistent visceral presence of structural violence and ongoing exclusion. This kind of art, the article maintains, can create spaces for increased understanding and relatedness, offering insight into how (inter)national politics impinge upon personal experiences and intimate (dis)identifications, while simultaneously opening up the well-established meanings to critical interrogation.

On 27 January 2017, President Donald Trump signed Executive Order No. 138802017: Protecting the Nation from Foreign Terrorist Entry into the United States, known as the “Muslim ban,” suspending the entry of foreign nationals from Iran, Iraq, Libya, Sudan, Somalia, Yemen, and Syria for a period of 90 days as well as suspending the United States’ refugee admissions programme for a period of 120 days. The Order also cut refugee admission numbers in half, and indefinitely suspended the admission of Syrian refugees (cf. Wadhia 1484). According to Trump, the idea behind the ban was to keep out “radical Islamic terrorists” (cf. Shear and Cooper), assuming that the nationals of Syria entering the US as refugees would remain a threat to the security of the nation. As a result of massive criticism by lawyers, NGOs, and journalists (cf. Ayoub and Beydoun), indicating that the order constituted a violation of a clause in the US Constitution prohibiting the favouring of one religion over another (Estrada et al. 3446), the order was suspended on 3 February 2017, while its reinstatement was rejected two days later by the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals in San Francisco (Estrada et al. 3446).

The Order was quickly replaced with another one, signed on 6 March 2017, which dropped the indefinite ban on entrants from Syria, rescinded the ban on Iraqis, and spelled out several exceptions, including lawful permanent residents, those paroled or admitted into the US, those admitted to travel, dual nationals of a country travelling on a diplomatic visa, and those granted refugee-related relief (Wadhia 1486). Again, as a result of challenges it received in federal courts, on 24 September 2017, the Order was replaced with a presidential proclamation introducing a third version of the ban, indefinitely blocking the entry of certain individuals from Iran, Libya, Chad, North Korea, Syria, Somalia, Venezuela, and Yemen. Even though two lower court rulings partially blocked the ban, the Supreme Court decided to uphold it, and it went into effect on 26 June 2018 (Estrada et al. 3446). Thus, after a series of tweaks, the “Muslim ban” was eventually implemented, complicating the situation of residents of and visitors to the US coming from the countries listed in the regulation.[3] The introduction of the “Muslim ban” was accompanied with a regular slashing of the refugee admissions cap—“from [an] Obama-era high of 110,000 refugees for [the] fiscal year 2017 to a low of only 18,000 refugees for [the] fiscal year 2019” (Hodson 268)—which testified to the unprecedented occurrence of the anti-Muslim, anti-refugee nexus on the US national stage (Hodson 269), resulting in the criminalization of both newly arriving refugees and those who had already been admitted to the US.

The above-described events must be read in a broader sociopolitical and legal context. One dimension of this is the so-called “Islamophobia industry,” which has a long history in the US, dating back to such crises as “the OPEC oil embargo (1973–1974), the Iranian hostage crisis (1979–1981), and the Rushdie Affair (1988–1989)” (Hodson 268; see also Kumar; Beydoun). Islamophobic rhetoric intensified in the US after the 9/11 attacks, contributing to a surge in the demonization of Muslims in the US (cf. Puar, Terrorist Assemblages; Puar and Rai). As Margaret Hodson explains, there are two crucial players in the Islamophobia industry in the US—ACT for America and the Center for Security Policy—whose activities add to the spreading of the anti-refugee sentiment in the nation. Operating both at the grassroots level and by lobbying state legislatures and Congress, since 2010 the two organizations have managed to persuade 14 states to enact anti-Sharia legislation while 201 anti-Sharia law bills have been introduced across 43 states, even though no attempts had ever been made in the US at passing any Sharia-based regulations (Hodson 270). Hodson claims that “[i]n justifying the Muslim ban, Trump follow[ed] the lead of Act for America and CSP in projecting standard Islamophobic fears of terrorism and civilization jihad onto the Muslim refugees specifically and U.S. Refugee Admission Program more generally” (274). All of this testifies to the current scale of Islamophobia in the US and the visible attempt at its institutionalization.

Another dimension of the context in which the anti-Muslim regulations have been implemented relates to a change in the national and religious profile of the refugees arriving to the US. Since the early 2000s, the US has started accepting a larger number of refugees from predominantly Muslim countries, partly owing to the sustained counterinsurgency wars in which the country has been involved. The war in Syria substantially added to this phenomenon. Thus, the presidential policy of slashing the refugee admission cap clearly coincided with the growing number of refugees from the Middle East region, and especially Syria, fleeing the atrocities of war and political violence. This produced a situation in which—through manipulative operations of the discourse on securitization (cf. Buzan, Wæver, and De Wilde; Wæver; Vuori; Kumar; Neal)—already vulnerable groups were exposed to further discrimination and violence, experiencing exclusion related to their religious or ethnic identity as well as to their national origins.

Haddad’s self-portraits included in the project A Question of History evoke representations already widely circulated in popular media discourses and associated with the contested “global war on terror” proclaimed by the George W. Bush administration in the direct aftermath of the 9/11 attacks. Instead of simply repeating the well-recognizable meanings, however, these artistic representations function simultaneously within several symbolic registers, activating broad semantic maps and producing layered understandings. They refer the spectator to the complex debates that erupted in the post-9/11 climate—tackling political torture, Islamophobia, sustained counterinsurgency wars, and anti-Muslim regulations—yet without offering any straightforward interpretations.

In my view, Haddad’s project succeeds in conveying the complexity of the intimate process of plastic, superfluous, and never completely accomplished (dis)identifications, being a part of the experience of many dislocated people, who are forced to negotiate—often excruciatingly—their sense of belonging in new places and new contexts. The concept of “interior frontiers” (Balibar, La crainte des masses; Masses, Classes, Ideas; Stoler)[4] serves as an effective lens to capture the multilevel symbolic operations of Haddad’s artwork as well as its functioning within the changing sociopolitical and legal circumstances. As Ann L. Stoler explains, “interior frontiers” do not refer solely to inside and outside of the nation; rather, rooted in the idea of cultural affinity (or “interior bonds”), they “mark distinctions among the good citizen, the sub-citizen, and the non-citizen, those with a place vs. those who are superfluous and have no place, citizen vs. subject, refugee, migrant” (xvii; italics in the original). Interior frontiers remain fragile sites of struggle, often operating as divisions which can be “silently and violently enforced” (xvii). As Stoler—following Étienne Balibar—underlines, they “enclose, imprison, and put in touch” (7; see also Balibar, Masses, Classes, Ideas 63), becoming internal to both the person and polity; this quality testifies to the concept’s diagnostic capacities and its opening to political effects (Stoler 8).

A critical employment of the figuration of “interior frontiers” to approach Haddad’s artistic work enables a broadened understanding of the extremities of the always-shifting self-identifications, (non)belongings, implications, and victimizations as experienced by many Muslim people in the post-9/11 US, a context significantly shaped by the exclusionary political discourses as well as increasingly restrictive and manipulatively enforced legal protocols. As Stoler explains: “With intangible sensibilities and immeasurable measure, interior frontiers are affective zones as well, where feeling (experienced as fear, humiliation, threat, longing, or shame) is indexical of political positioning in the making” (22). As my analysis demonstrates, Haddad’s work well exemplifies the complex nature not only of how interior frontiers are delineated and imposed, but also of how they are experienced and felt.

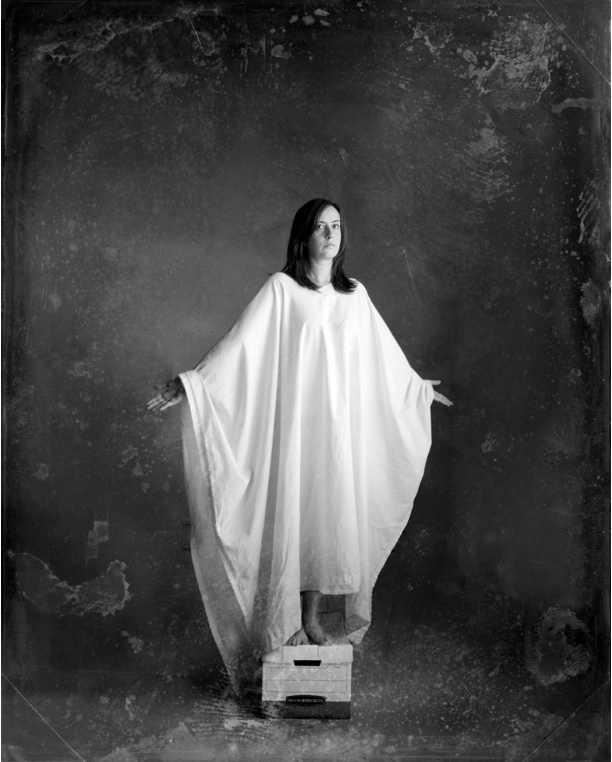

Haddad’s Reenactment—Part 1 (Fig. 1), one of the prints in A Question of History, displays the figure of the artist dressed in a long, white robe, standing on a cardboard box, barefoot, with her hands out to both sides, and with a sombre, incredulous look directed at the camera. Another picture, Reenactment—Part 2 (Fig. 2), portrays the standing artist dressed in a jumper and jeans and wearing a pair of moccasins. In her right hand she is holding a leash, unattached to any object; her contemplative look remains fixed on the other end of this unusual prop.

Fig. 1. Lara Haddad, Reenactment—Part 1, 2015–16. Transfer print on aluminium, 24” x 19.2”. Courtesy of the artist.

Fig. 2. Lara Haddad, Reenactment—Part 2, 2015–16. Transfer print on aluminium, 24” x 19.2”. Courtesy of the artist.

Although seemingly innocent in form and composition, and modest, even minimalist, as far as the artistic means necessary for their production are concerned, in the post-9/11 imaginary landscape, these visual representations of a young Muslim woman, newly arrived in the US, immediately lose their innocuous tint. The two self-portraits clearly position themselves within the well-recognizable panorama of images associated with the culture of torture, systematic surveillance, and ruthless persecution of those considered as terror suspects and deprived of their basic rights. Such a culture both emerged from and itself co-constituted a varied constellation of antiterrorist practices undertaken, both lawfully and unlawfully, in different parts of the world against various state and non-state actors. Consolidated in the US in the aftermath of the devastating 9/11 attacks on the WTC and Pentagon, it has subsequently gained significant visibility across popular media (Adams; Athey), stimulating political debates about the ethical dimension of the means employed as part of the state-sponsored violent policies mobilized against those who figured as a potential threat to the security of the American nation. Given this political and cultural context, Haddad’s self-portraits are reminiscent of the disturbing pictures of the brutally abused prisoners, considered to be terror suspects, humiliated by US guards in extraterritorial military bases and detention centres, such as Abu Ghraib in Iraq, Bagram and Kandahar in Afghanistan, and Guantánamo Bay in Cuba.[5] The afterlife of these terrifying images in literature, film, art, and activism testifies to the complex entanglement of political discourses and cultural representations in the post-9/11 context (cf. Adams; see also Eroukhmanoff).

But the cultural iconosphere related to the politics of torture and violence in the aftermath of 9/11 is not limited to the images of abused terror suspects undergoing coercive interrogations in US detention centres. It remains equally pervaded with much more diversified representations of violence and atrocity, including those performed by the representatives of the groups against which the US-led counterinsurgency wars have been waged. Execution (Fig. 3), another print in Haddad’s series, portrays the artist wearing a black t-shirt and—in a theatrical, staged gesture, with her left hand stretched to the front—carrying half of a pineapple, held up high to the camera, with an aim to clearly display the object to the viewer. Her face still and emotionless, the woman is looking directly into the object-glass, capturing and overwhelming the spectator with her focused, dispassionate gaze. Simple in form, even inconspicuous, the composition of the picture again re-enacts scenes associated with the post-9/11 culture of violence, this time, however, drawing attention to the ferocities perpetrated by the jihadist extremists.

The terrifying recordings of beheadings—standing for what Lisa J. Campbell calls “the modern day version of the spiked head” (605) as well as embodying “terrorizing rituals with theatrical overtones” (609)—have been disseminated by terrorist groups in an attempt at spreading fear within Western societies. Despite the long history of ritual beheadings in different geographical contexts (cf. Campbell),[6] these videotaped executions have become an integral component of the 21st-century culture of fear and abhorrence, adding impetus to the policy of justifying many highly controversial means of coercion employed against individuals suspected of being involved in terrorist activities. The presence of videotaped beheadings across a wide array of media has also contributed considerably to the increasing demonization of Muslims through a discourse which clearly conflates all Islam with the terrorism perpetrated by a few Islamists, and which stresses, as Alex Adams underlines, “the irreconcilability of Islam with the secular modernity of the West,” dehumanizing Muslims “so that perpetrating torture on them seems like less of a crime” (16; see also Butler).

Fig. 3. Lara Haddad, Execution, 2015–16. Transfer print on aluminium, 24” x 19.2”. Courtesy of the artist.

By bringing together a series of self-portraits representing a woman being a part of practices of violence, either as victim or victimizer, Haddad seems to situate her work in the context of broader discussions on political torture. Her artwork exposes how these debates tend to juxtapose the performances of “civilized” representatives of Western culture versus those of “uncivilized” Muslims, especially by differentiating between the distinctive natures of violent activities in which they are all involved.

From the perspective of law, political torture—especially if enacted with the authorization of a democratic state—figures as an exceptionally contested terrain (cf. Lazreg; Rejali). The 1984 Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (UNCAT) defines torture as “any act by which severe pain or suffering, whether physical or mental, . . . is intentionally inflicted on a person,” including acts when “such pain or suffering is inflicted by or at the instigation of or with the consent or acquiescence of a public official or other person acting in an official capacity” (part 1, article 1). However, regulations introduced in late 2001 and throughout 2002 by the Bush administration in the context of “a state of exception” tended to render some forms of torture—through manipulative mobilization of selected legal protocols, some of which were clearly colonial in nature (cf. Gregory; Kaplan)—into sanctionable acts. For instance, the practice of the externalization of US detention centres had the function of allowing flexibility in using torture against terror suspects by formally placing these institutions outside US jurisdiction,[7] thus turning them into something that Amy Kaplan describes as “a legal black hole, a legal limbo, a prison beyond the law” (831).[8] In such a situation, making use of “contorted legal geo-graphing” (Gregory 416), the abused prisoners incarcerated outside the US could not benefit from the protection of the US legal system,[9] while the latter was partly released from the accountability for violent developments taking place in these premises (cf. Kaplan 851). Such a ruling blurred—perhaps intentionally—the border between the “inside” and the “outside” of US jurisdiction, while simultaneously consolidating the boundary between the subject of the nation under threat (i.e. those who belong within “interior bonds”) and the threatening others (i.e. those excluded by “internal borders”), the latter positioned either within or without the nation.

The White House worked intensely to set aside the Geneva Convention and redefine the captured fighters as “unlawful combatants”—a category that, in Kaplan’s words, “erodes the distinctions among citizens and aliens, immigrants and criminals, prisoners and detainees, terrorists and refugees” (853). Instead of treating them as prisoners of war (POWs) (Robertson 532; see also Joynt), which would require their handling in compliance with international regulations, the official policy established that “the humane treatment of prisoners in the war on terror was optional” (Gourevitch and Morris 48). As not formally associated with any state, and not wearing any uniforms or official insignia while being captured, the detainees were not considered to be POWs and could thus claim neither protection nor adequate treatment under the Convention. Since they were not imprisoned within US territory, their right to challenge their detention as well as the possibility of filing a writ of habeas corpus were not operative. Such regulations made their bodies—situated beyond the internal borders and excluded from the interior bonds—available to illegal violence. As far as acceptable means of interrogation are concerned, an opinion from the Department of Justice, delivered in the summer of 2002 after a formal request from the White House had been placed, stated that “only ‘the most extreme acts’ qualify as torture, and they must be committed with the ‘precise objective’ of inflicting pain ‘equivalent in intensity to the pain accompanying serious physical injury, such as organ failure, impairment of bodily function, or even death’” (Gourevitch and Morris 48). In light of this interpretation, such forms of torture as hooding (evoking disorientation due to sensory deprivation), waterboarding (simulated drowning), or forced nudity and sexual taunting or assault—extensively practiced by guards in extraterritorial US Army-led prisons—did not formally count as political torture.

With such a contorted understanding of torture, so-called “clean torture” (Rejali 415)—or non-scarring torture techniques leaving no lasting, visible traces on prisoners’ bodies, a form of coercion much preferred by democratic states (Rejali 410)—is in the dominant discourse juxtaposed against the extreme violence practiced by jihadist fighters, with beheadings being the most extreme embodiment of their inhumane cruelty and ruthlessness. Such discursive tactics contribute to the delineation and subsequent sharpening of a fundamental differentiation between the acts of torture performed by US troops in an attempt to protect the nation and the violent acts that are represented as committed out of pure hatred and encouraged by zealous religiosity. Given such framing of these instances of violence, the acts of atrocity performed against the dehumanized, shamed, and sexually humiliated bodies of terror suspects (Puar, “On Torture”) are redefined in terms of necessity, even survival, in the face of a potential terrorist threat these bodies might pose for the American people. As far as discursive representation of the experience of the US troops/citizens is concerned, this repositioning signals a significant shift from language of perpetration to that of (hypothetical) victimhood and enduring trauma (cf. Abu El-Haj). Such a move fuels Islamophobia, sanctioning war waged in national rather than humanitarian terms.

Despite being backed with legal regulations, the discursive process of delineating borders between “us” and “them,” “right” and “wrong,” and “acceptable” and “unacceptable” violence remains paradoxical. The partial and selective legalization of political torture understood as a measure to prevent more ferocious forms of violence practiced by Islamist extremists—if nevertheless morally ambiguous—puts the solutions developed by the ad-hoc architects of the US legal system in a proximity to those whose activities are to be countered by the very scheme, and with which the implementation of manipulative legal developments is rhetorically justified. In fact, the delineation of distinction between the US citizens and terror suspects rests on a partial erasure of the experiential difference between the practices of violence in which both sides are involved. In this process, the demarcation of differences resulting in the demonization of all Muslims justifies the rapprochement as far as the violent performances on their bodies are concerned. At the same time, the space for political and moral critique becomes dramatically narrowed, both in the discourse and its attendant practices.

In a somewhat provocative gesture, by placing the different representations of torture associated with the “global war on terror” within the same series of self-portraits, Haddad seems to deliberately blur the differences between these allegedly dissimilar renderings of acts of violence. Indistinguishable in style, form, and composition, produced in the same aesthetic convention, and with the use of identical artistic techniques, the prints function as a coherent whole commenting on the political developments in the post-9/11 context and the cultural discourses that emerged around these devastating events. Monochromatic, featuring a figure of the same woman situated against a blank background, and in the company of a very limited number of props, Haddad’s self-portraits seem to purposefully avoid the dilution of the aesthetic language, in order not to distract the attention of the spectator from her staged rehearsal of the already widely recognizable images of violence.

Nevertheless, Haddad’s re-enactments remain intentionally incomplete, trickily positioning themselves in opposition to the titles that the artist attributes to these works. Through their aesthetic minimalism, and due to a strategy of using a very limited collection of supports necessary for her performances, the artist’s representations succeed in both mimicking the original frames and revising, even mocking, them at the same time. Thus, by opening the well-recognizable meanings to processes of substantial erosion, Haddad’s works modify the semantic maps that these visual conventions usually activate, dislocating the representations’ original meanings and inviting critical contestation. This contributes to the implosion of simplified discursive polarizations weaponized for the purpose of justifying “the global war on terror.”

The artist’s self-portraits function within at least two—to a certain extent contradictory—visual registers. While mimicking their convention and composition, the pictures simultaneously function as sort of negatives of the infamous originals. In Reenactment—Part 1, Haddad reverses the colours (her robe is white) and the gender of the pictured terror suspect (as a Muslim female, she is discursively positioned as one who must be “saved” by the US troops rather than as one who is violently abused by them); her face is uncovered and displays a concrete identity (while the victim in the original framing remained anonymous). She actively looks back into the camera, instead of her figure solely being available to the spectator’s gaze. In Reenactment—Part 2, Haddad is dressed like a civilian, and the leash that she holds is not attached to anything or anyone (the victimized prisoner, present in the original frame, is not included in the artist’s rehearsal). Through reference to her gender, as much as her status as a US resident, she puts herself in the position of a woman-victimizer, humiliating male prisoners, defining herself as an oppressor, perhaps even a traitor, of her own cultural identity held together by interior bonds. Eventually, in Execution, she again breaks with the visual convention of the original videos, exposing her face as the perpetrator (always covered in the original videotaped accounts), wearing just a simple t-shirt (instead of arms and heavy equipment), and—in a gesture of sad, devastating mockery—displaying a portion of a fruit rather than a decapitated head.

Through these modest, albeit significant, modifications, the artist is capable of opening new interpretative planes, partly purifying the original shots from the ideologically shaped cultural values and making them available to new affiliations. While artistically engaging with visual frames that have become iconic for the culture of torture, surveillance, and persecution, Haddad manages to put these well-known representational conventions under scrutiny, making them present and absent at the same time. As she explains: “I am beginning to distill new values and beliefs from the remnants of a social construct that I don’t adhere to anymore,” with an aim “to uproot fears, self-censorship and self-discipline that this system planted in me” (10).

The minimalism of artistic means mobilized to produce A Question of History enables an exposition of the diversity of sociopolitical associations that her project puts in motion. But it also seems to uncover the dramatic extremities of intimately experienced (dis)identifications. Consisting of a series of self-portraits, her art directly engages her body, functioning as a plastic, living memory machine, actively processing the information and inputs, re-enacting the cultural clichés, while striving to live normally under the extreme conditions of ongoing violence, persistently impinging on the artist on an everyday basis. Haddad writes:

Through my work, I am unpacking the fragments of my identity. . . . People may choose to see me as a war victim or a perpetrator. Whenever I speak, I confirm that I am the “other.” In a space of uncertainty, I might not be either, yet a very small change in my circumstances would have made me one or the other. (10)

Moving between the extreme positions of victim on the one hand and victimizer on the other, the locations partly blurred but also partly sustained through the discourse reasserting “interior frontiers,” the artist—somewhat unwillingly—implicates herself in the complex economy of legacies of political violence (cf. Rothberg), alluding to the difficulties of situating herself within the tangled landscapes of formal and informal post-9/11 anti-Muslim developments.

Immersed in the plethora of contradictory cultural significations, Haddad reclaims her body and reintegrates it into the process of metamorphous culturo-material, plastic becomings, or a constant negotiation of the intimately experienced territory of the “interior frontier.” As Catherine Malabou elaborates, such plasticity must be understood “as a form’s ability to be deformed without dissolving and thereby to persist throughout its various mutations, to resist modification, and to be always liable to emerge anew in its initial state” (The New Wounded 58). Malabou also points to “the series of transformations” as something “that can always ‘be annulled’ so that this ‘unique form’ can reappear” (The New Wounded 58). Thus, “[p]recisely and paradoxically, plasticity characterizes both the lability and the permanence of this form” (Malabou, The New Wounded 58). It seems that Haddad’s work rests on such an understanding or intimate experience of plastic metamorphoses. It embodies a parade of self-annulling identifications, a constant migration between the oppositional poles of culturally sustained polarizations, and a shifting dislocation of intimate subjectivities. Through her art, Haddad thus engages in a process of self-effacement and re-emergence in a new—yet the same—form, or an ongoing practice of creating dissonances and noises resulting from the violent clashing of visual conventions.

Through a series of self-portraits, the artist strives to create a fiction of herself, a fragile “expression of the traumatized psyche” (Malabou, “What is Neuro-Literature?” 81). Such plasticity may be a result of rapture, an accident (of war, violence, migration) which damages one’s subjectivity and from which one emerges as an “unrecognizable persona whose present comes from no past” (Malabou, The Ontology 2), a transformation that leaves one “dumb and disoriented” (Malabou, The Ontology viii). A series of self-portraits, capturing intimate experiences of the artist herself, seems to signal the extremities of the process of identifying with the re-enacted positions while simultaneously placing these identifications under scrutiny. The attempts at denying and rectifying them, or constantly confusing oneself with their contradictory contents, expose the vulnerability and fictionality of such self-positionings. The portrayed person “becomes a stranger to herself, who no longer recognizes anyone, who no longer recognizes herself, who no longer remembers herself,” a person “in a state of emergency, without foundation, bareback, sockless” (Malabou, The Ontology 6).

By physically putting herself in the positions already defined for her in the available discourse, albeit personally experienced as not hers at all, and by undoing their content and lessening their overload (Foucault 23), the artist seems to incessantly interrogate her belonging and how it is affected by the politics of the day. In such a context, Haddad’s project, disclosing the complexity of positionality, seems to suggest a means of survival in a political reality which complicates, even destroys, notions of subjectivity, and which remains marked by accumulative traumas of structural exclusions, dislocations, and violence. It also alludes to the process of negotiating the extreme conditions of dwelling in the zone of inbetweenness, under a constant pressure of having to “name” oneself, or of running the risk of being externally (mis)recognized. In the idiom of “interior frontiers,” this process refers, in Stoler’s words, to “how states harness individuals’ affective ties, marshaling distinctions that make up who they imagine themselves to be, need to be to secure presence and dwelling, what they need to master to know they belong in their surroundings, and not least what they need to master in themselves” (23). Through the imposition of “interior frontiers,” in a territory in which the distinction between what is “interior” and what is “internal” remains loose, people are shaped into specific “political subjects by the dispositifs of governance” (Stoler 23).

Reinterpretations of legal regulations in the post-9/11 US, as discussed earlier in this article, consisted of defining new, reasserting old, and eroding some of the (invisible) borders structuring not only the US but also global society. The contorted redefinition of the geographical territorializing of US jurisdiction paralleled the selective application of legal protocols to particular individuals and, in particular situations, redefining the political contours of cultural (non)belonging. The different versions of the “Muslim ban” in fact rearticulated—in a slightly modified form—the same strategy of criminalizing certain groups of individuals based on their ethnic/religious identity and representing them as a potential threat to the integrity of the American nation. Those whose bodies had once been available to illegal forms of violence have now again been exposed to actions of violence. Such a policy translated into a growing conflation of the figure of the refugee and that of the criminal, further increasing the vulnerability of people at risk. As Stoler explains, for those “hugging a border’s edges and excluded from its protection, as much as for those seeking security and refuge in its sheltered space” (8), thus understood interior frontiers create conditions “that affect up close their ‘being’ in as much they are subject to being in a physical, legal, and psychic space that is neither ‘this nor that’” (22; see also Balibar, La crainte des masses 383). Engaging with these problematic delineations, Haddad’s A Question of History probes the politically saturated discursive frames through which violence is approached and how it happens to be weaponized for the purpose of advancing the political “interests” of the nation.

By positioning herself differently within the discursively established locations—the “cultural modes of regulating affective and ethical dispositions through a selective and differential framing of violence” (Butler 1)—Haddad, through plastic (dis)identifications, succeeds at interrupting these normative schemes and opening them to subsequent annulation. Aware of the fact that representation should be understood as “a moral problem with political consequences” (Athney 14), the artist opts for a more condensed means for engaging her audiences. Inviting affective affiliations, critical (mis)recognitions, and inventive interrogations, rather than offering straightforward messages and outspoken interpretations, Haddad’s work avoids playing according to the state’s oppressive rules, instead mobilizing new spaces for creative questioning. At the same time, however, her art may offer an insight into how certain political mechanisms work and how their effects are intimately negotiated. It can therefore serve as a powerful means to expose conditions of political and personal extremity defined through interior bonds and internal borders, as well as to represent “lives lived under the duress of an extreme made everyday” (Victor).

Abu El-Haj, Nadia. Combat Trauma: Imaginaries of War and Citizenship in post-9/11 America. Verso, 2022.

Adams, Alex. Political Torture in Popular Culture: The Role of Representations in the Post-9/11 Torture Debate. Routledge, 2016. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315644561

Athey, Stephanie. “Rethinking Torture’s Dark Chamber.” Peace Review, vol. 20, no. 1, 2008, pp. 13–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/10402650701873676

Ayoub, Abed, and Khaled Beydoun. “Executive Disorder: The Muslim Ban, Emergency Advocacy, and the Fires Next Time.” 22 Michigan Journal of Race & Law, vol. 215, 2017, pp. 228–33. https://doi.org/10.36643/mjrl.22.2.executive

Balibar, Étienne. La crainte des masses: politique et philosophie avant et après Marx. Galilée, 1997.

Balibar, Étienne. Masses, Classes, Ideas: Studies on Politics and Philosophy Before and After Marx. Translated by James Swenson, Routledge, 1994.

Beydoun, Khaled A. “‘Muslim Bans’ and the (Re)making of Political Islamophobia.” University of Illinois Law Review, vol. 5, 2017, pp. 1733–74.

Butler, Judith. Frames of War. When is Life Grievable? Verso, 2009.

Buzan, Barry, Ole Wæver, and Jaap De Wilde. Security: A New Framework for Analysis. Lynne Rienner, 1998. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781685853808

Campbell, Lisa J. “The Use of Beheadings by Fundamentalist Islam.” Global Crime, vol. 7, no. 3–4, 2006, pp. 583–614. https://doi.org/10.1080/17440570601073384

Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (UNCAT). OHCHR, 10 Dec. 1984, https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/convention-against-torture-and-other-cruel-inhuman-or-degrading, accessed 6 Nov. 2022.

Eroukhmanoff, Clara. “‘It’s not a Muslim ban!’ Indirect Speech Acts and the Securitisation of Islam in the United States Post-9/11.” Global Discourse, vol. 8, no. 1, 2018, pp. 5–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/23269995.2018.1439873

Estrada, Emily P., Alecia D. Anderson, and Angela Brown. “#IamaRefugee: Social Media Resistance to Trump’s ‘Muslim Ban.’” Journal of Refugee Studies, vol. 34, no. 3, 2021, pp. 3442–63. https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/feaa125

Foucault, Michel. Maurice Blanchot: The Thought from Outside. Translated by Brian Massumi, Zone, 1987.

Gourevitch, Philip, and Errol Morris. Standard Operating Procedure. Penguin, 2008.

Gregory, Derek. “The Black Flag: Guantánamo Bay and the Space of Exception.” Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography, vol. 88, no. 4, 2006, pp. 405–27. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0435-3684.2006.00230.x

Haddad, Lara. “A Question of History.” Master of Fine Arts Thesis Exhibition Catalogue, U of Arizona P, 2016, p. 10.

Hodson, Margaret. “‘Modern Day Trojan Horse?’ Analyzing the Nexus between Islamophobia and Anti-Refugee Sentiment in the United States.” ISJ, vol. 5, no. 2, 2020, pp. 268–82. https://doi.org/10.13169/islastudj.5.2.0267

“Johnson v. Eisentrager, 339 U.S. 763 (1950).” Justia U.S. Supreme Court, 1950, https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/339/763/, accessed 14 Dec. 2022.

Joynt, Anne E. “The Semantics of the Guantánamo Bay Inmates: Enemy Combatants or Prisoners of the War on Terror?” Buffalo Human Rights Law Review, vol. 10, 2004, pp. 427–41.

Kaplan, Amy. “Where is Guantánamo?” American Quarterly, vol. 57, no. 3, 2005, pp. 831–58. https://doi.org/10.1353/aq.2005.0048

Kumar, Deepa. Islamophobia and the Politics of Empire. Haymarket, 2012.

Lazreg, Marnia. Torture and the Twilight of Empire: From Algiers to Baghdad. Princeton UP, 2008. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400883813

Malabou, Catherine. The New Wounded: From Neurosis to Brain Damage. Translated by Steven Miller, Fordham UP, 2012.

Malabou, Catherine. The Ontology of the Accident: An Essay on Destructive Plasticity. Translated by Carolyn Shread, Polity, 2012.

Malabou, Catherine. “What is Neuro-literature?” SubStance: A Review of Theory and Literary Criticism, vol. 45, no. 2, 2016, pp. 78–87. https://doi.org/10.1353/sub.2016.0024

Neal, Andrew W. “Normalization and Legislative Exceptionalism: Counterterrorist Lawmaking and the Changing Times of Security Emergencies.” International Political Sociology, vol. 6, no. 3, 2012, pp. 260–76. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-5687.2012.00163.x

Proclamation on Ending Discriminatory Bans on Entry to The United States. The White House, 20 Jan. 2021, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/presidential-actions/2021/01/20/proclamation-ending-discriminatory-bans-on-entry-to-the-united-states/, accessed 14 Dec. 2022.

Puar, Jasbir. “On Torture: Abu Ghraib.” Radical History Review, vol. 93, 2005, pp. 13–38. https://doi.org/10.1215/01636545-2005-93-13

Puar, Jasbir. Terrorist Assemblages: Homonationalism in Queer Times. Duke UP, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822371755

Puar, Jasbir, and Amit S. Rai. “Monster, Terrorist, Fag: The War on Terrorism and the Production of Docile Patriots.” Social Text 72, vol. 20, no. 3, 2002, pp. 117–48. https://doi.org/10.1215/01642472-20-3_72-117

Rejali, Darius. Torture and Democracy. Princeton UP, 2007.

Robertson, Geoffrey. Crimes Against Humanity: The Struggle for Global Justice. Penguin, 2006.

Rothberg, Michael. The Implicated Subject. Beyond Victims and Perpetrators. Stanford UP, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781503609600

Shear, Michael, and Helen Cooper. “Trump Bars Refugees and Citizens of 7 Muslim Countries.” The New York Times, 27 Jan. 2017. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/01/27/us/politics/trump-syrian-refugees.html, accessed 14 Dec. 2022.

Stoler, Ann L. Interior Frontiers: Essays on the Entrails of Inequality. Oxford UP, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190076375.001.0001

Victor, Divya. Preface. “Extreme Texts.” Jacket2, 20 June 2019, https://jacket2.org/feature/extreme-texts, accessed 10 Oct. 2022.

Vuori, Juha A. “Illocutionary Logic and Strands of Securitization: Applying the Theory of Securitization to the Study of Non-Democratic Political Orders.” European Journal of International Relations, vol. 14, no. 1, 2008, pp. 65–99. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354066107087767

Wadhia, Shoba Sivaprasad. “National Security, Immigration and the Muslim Bans.” 75 Wash. & Lee L. Rev., vol. 1475, 2018, pp. 1475–1506.

Wæver, Ole. “Securitisation and Desecuritisation.” On Security, edited by Ronnie D. Lipschutz, Columbia UP, 1995, pp. 46–87.