Source: Siberian Memorial Museum in Białystok, sign. MPS/D/1483.

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8735-2655

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8735-2655

University of Lodz

Archives of Lodz

e-mail: lilianna.ladorucka@uni.lodz.pl

Abstract

The Committee for Polish Children in the USSR operated in the years 1943–1946. It was established on June 30, 1943 in Moscow following a political left-wing initiative. The Committee was a care-giving institution, fully in line with the Soviet system ideals. One of the most important matters tackled by the Committee was the repatriation of the youngest Polish citizens to their homeland. It was the subject of meetings, discussions and many hours of talks with the Soviet authorities. This issue was one of the most difficult tasks carried out by the Committee employees. The repatriation of orphanages to Poland lasted from January to August 1946.Keywords: Repatriation, orphanages, World War II, Committee for Polish Children in the USSR, Poland, Gostynin

Abstrakt

Komitet do spraw Dzieci Polskich w ZSRR funkcjonował w latach 1943–1946 r. Został powołany 30 czerwca 1943 r. w Moskwie z inicjatywy środowisk lewicowych. Komitet był opiekuńczą instytucją radziecką. Wszelkie jego działania były wzorowane na rosyjskim systemie oświatowym.Słowa kluczowe: repatriacja, domy dziecka, II wojna światowa, Komitet do spraw Dzieci Polskich w ZSRR, Polska, Gostynin

As a result of four deportations carried out in 1940–1941, Polish citizens found themselves in the vast territory of the USSR.

On July 30, 1941, an agreement was signed in London between the government of the USSR and the Polish government. In this context, the name of Sikorski-Mayski treaty is commonly used. At that time, diplomatic relations were resumed, exchange of ambassadors was announced, the formation of the Polish Army in the USSR, as well as military cooperation were declared (Sprawozdanie z działalności Ambasady R.P. 5, 32; Dokumenty i materiały, t. VII, 232–33; Czapski 48; Sprawa polska 226–229; Szubtarska 16–19; Rutkowski 216; Jonkajtys-Luba 13–14; Żaroń, Kierunek wschodni 50–55; Boćkowski 145; Siemaszko 158–59; Oppman, Wroński, Englert 63–67). In a secret minutes attached to the above-mentioned agreement, the Soviet authorities declared “granting amnesty to all Polish citizens who are currently deprived of liberty in the territory of the USSR, either as prisoners of war or on other sufficient grounds” (Historia dyplomacji polskiej 224–225; Materski 614–615). Another result of the agreement was the creation of Polish Army in the USSR, under the command of general Władysław Anders.

The Polish embassy in Moscow (which was evacuated to Kuybyshev in October 1941) repeatedly appealed to the international community for helping the civilian population. The youngest – Polish children – were in the worst situation. Their fate was tragic, “everyday life was dominated by hunger, disease, and hard work beyond strength to death – the inseparable companions of their ‘stolen childhood’” (Szubtarska 124).

In 1942 ambassador Stanisław Kot estimated that there were approximately 160,000 Polish children in the USSR. We can state with full conviction that this number was certainly overstated by several tens of thousands.[2]

The Polish army and the accompanying civilians were evacuated from the USSR in two stages: March-April and August-September 1942.

In a statement of the Central Register Office (a report prepared by Zygmunt Sroczyński in Teheran on August 20, 1943), it was noted that 19,984 children were evacuated from the USSR (Udzielona pomoc i opieka 12; Żaroń, Ludność polska 225).[3]

According to the figures disclosed in the first half of 1943 by the NKVD (Soviet Commissariat of Internal Affairs), there were 66,718 children (under 16) in the USSR. On the other hand, the Committee for Polish Children in the USSR had a different assessment, in which the number of children (under 18) was estimated at around 66,300 (Głowacki, Na pomoc zesłańczej 132–133).

The main aim of the article is to show the difficult process of repatriating Polish orphanages which were located in the USSR to Poland in 1946.

Already difficult diplomatic relations with the USSR worsened in the second half of 1942. In the first months of 1943, the Soviet authorities “took over Polish social welfare institutions in the USSR along with supplies stored in their warehouses” (Ciesielski, Hryciuk, Srebrakowski 251).

The approach and actions of the Soviet side were relentless. Any efforts to abide by and respect previously agreed upon agreements have been unsuccessful. In the spring of 1943, diplomatic relations were severed. A group of left-wing activists became active in the USSR and formed a political body named Union of Polish Patriots during a founding Congress in Moscow already at the beginning of June 1943. Its program stressed the “importance of alliance with the Soviet Union” (Wolna Polska, 15 (1943) 4).

A dozen or so days later (June 30, 1943, Resolution No. 710), the Committee for Polish Children in the USSR[4] was formed under the People’s Commissariat of Education (Kormanowa 194; Skrzeszewski 38; Syzdek 180; Komunikaty Zarządu Głównego 4; Komitet do spraw polskich 4). The Committee was a care-giving institution, fully in line with the Soviet system ideals. However, in extremely difficult war conditions, it was the only institution in the USSR which managed to save lives of Polish and Jewish children residing in the vast territory of the Soviet state.

The first meeting of the Committee for Polish Children in the USSR took place on July 10, 1943. The subject of debate was detailed registration of children. It was the most important and at the same time an extremely difficult task. Not only was there lack of information about their location and quantity, but also there were no indications as to whether they had already been helped by any children’s institution. The most urgent task was to create a support system in the form of orphanages, schools, kindergartens, nurseries and boarding houses. The emphasis was correctly placed on the urgent provision of food and sanatorium-type care for the most vulnerable children. The People’s Commissariat of Healthcare of the USSR and the People’s Commissariat of Light Industry of the USSR[5] were to help in achieving the aforementioned goals (Ladorucka 433–454).

In July 1944, the Polish Committee of National Liberation was established in Moscow. It sparked hope for the realization of a long-awaited return to the homeland. Unfortunately, the implementation was still far in the timeline, and Poland to which exiles returned after many years of humiliation, was already a completely different country compared to the one they remembered and missed. Hunger, tears, hopelessness and death were everyday companions of misery. The cruel time of war showed that “the presence of Poles in Siberia was always under the sign of slavery, and this tradition has remained alive to this day” (Kuczyński 19).

One of the most important matters tackled by the Committee for Polish Children in the USSR was repatriation. It was the subject of numerous tedious meetings, discussions and many hours devoted to talks with the Soviet authorities. The foregoing issue was one of the most difficult tasks carried out by Committee for Polish Children in the USSR employees. The repatriation of orphanages to Poland began in January 1946.

Meanwhile, in 1945, children from one facility located in the USSR returned to their homeland. On March 21, 1945 Committee for Polish Children in the USSR (in letter No. 12/411) turned to the USSR Deputy People’s Commissar for Finance Ja. I. Goliev with a request for assistance regarding the repatriation of the first group of children (50 people) and 7 accompanying staff members from the orphanage in Karakulino (Udmurt ASSR) to Poland. The children were to be transported in April from the Sarapul to Białystok[6] (Żeglicki 5).

To achieve this goal, the Committee for Polish Children in the USSR needed 25,000 rubles (15,000 rubles to cover costs for two passenger carriages for transporting children and their guardians, and 10,000 rubles for the purchase of food and other travel expenses).[7]

On March 27, 1945, the head of the Committee Finance Department (Gieorgij Ivanovich Kaczmar) sent another letter to the People’s Commissariat of Finance of the USSR, in which he repeated his appeal for an urgent approval of the requested amount.[8]

On April 4, 1945, the Committee chairman, Sergey Aleksandrovich Novikov (order No. 19), obliged Ekaterina Vasilyevna Koniachina (head of the Department of Orphanages) to organize the transport to Poland for the above-mentioned group of children with their guardians in April 1945. The duties of the head of transport were entrusted to S. M. Pevzner (director of the orphanage in Karakulino). He was accompanied by R. N. Pinkusfeld (a doctor) and Gieorgiy F. Butlov – Senior Inspector of the Committee Pre-school Department[9](Wychowankowie Domu Dziecka 1).

Despite many efforts, the full amount necessary to ensure safe travel of children from the orphanage in Karakulino to Poland was still missing. Ultimately, the Committee organized the transport, clothes, shoes and food, and transported children to one collective point. The People’s Committee on Education of the RSFSR ordered that funds from the allocated budget, be assigned to this purpose. The aforementioned problems resulted in constant delays in departure. Ultimately, the transport with children left from the Belarusian Railway Station in Moscow on May 29, 1945.[10]

The train reached Białystok on June 1, 1945. To Poland has arrived 42 children. The children were solemnly welcomed by a Polish delegation in the hall of the Railroaders’ House. The following day, during a ceremonial academy at the Municipal Theater, Butlov presented a lecture on the forms of care given to Polish children in the USSR. Director Pevzner was awarded the Silver Cross of Merit. The elements of Soviet propaganda and admiration for its authorities were cleverly weaved into the presentation. Apparently, a telegram was sent to Moscow, stating that „only the Soviet government could raise teachers who devoted themselves in such a humanitarian and selfless manner to the children of a fraternal Slavic nation”![11] (Przyjazd Karakulińskiego Domu Dziecka 1; Documents and Materials 478–481).

On July 6, 1945, an agreement was signed in Moscow between the Provisional Government of National Unity of the Republic of Poland and the government of the USSR on the “right to change Soviet citizenship by persons of Polish and Jewish nationality living in the USSR, and on their evacuation to Poland, and the right to change Polish citizenship by persons of Russian, Ukrainian, Belarusian, Ruthenian and Lithuanian nationality, living on the territory of Poland, and about their evacuation to the USSR”. The implementation of this agreement was managed by the Soviet-Polish Mixed Commission based in Moscow. Dr. Henryk Wolpe led the Polish delegation. The repatriation was planned to end on December 31, 1945 (Głowacki, Ocalić i repatriować 208; Głowacki, Problem repatriacji wychowanków 34; Ciesielski 57).

From the very beginning, it was an unrealistic task for the scheduled timeline due to a large extent of organizational and regulatory issues that had to be dealt with. As a result, the burden of preparation was to a large extent assigned to the Committee for Polish Children in the USSR.

The Committee faced hard work daily, undertaking activities to efficiently carry out the repatriation of Polish children to their homeland. Detailed circulars with instructions on the return of children to Poland were sent to the relevant institutions at the regional, national and republican levels. They included financial means assigned per 1 pupil, list of groceries, outerwear, underwear and bed linen granted during the trip. In addition, following the departure of adult Polish citizens, care-giving institutions operating on behalf of the Committee for Polish Children in the USSR were mentioned to be dissolved. The document also specified the order and number of children who would be repatriated to Poland. From the youngest Polish citizens staying in orphanages for Polish children, to children who found custody in Soviet institutions and children staying in Soviet foster families (patronage).

The information that had to be included on the prepared lists was meticulously documented (surname, first name, father’s name, nationality, place of birth, when and from where they came to the USSR; additionally, the same information was recorded for the children’s parents). Children from orphanages who had parents residing in the USSR were added to the lists upon their parents’ consent and after giving up their Soviet citizenship. Children under 14 years old, whose parents were confined, were not subject to evacuation. Children from 14 to 18 who wanted to go to Poland had to submit applications, which were evaluated by representatives of local authorities and competent officials of the education authorities[12] (Z dziejów Polaków 201).

In the guidelines for the Committee for Polish Children in the USSR (No. 7/1183) sent on August 6, 1945 to Committee on Education SSR, ASSR and heads of district (national) education departments, its chairman noted “for cases in which the deadline for commencing repatriation has not yet been established […] the renovation of school buildings should be continued, fuel for space heating should be provided, and students should have necessary school aids”. In the letter he sent, he encourages Polish teachers to participate in pedagogical meetings organized by the Committee in August 1945, regarding discussions on teaching the Polish language, history and geography of Poland. He emphasized the importance of revising the material with students in the beginning of the school year. Children leaving for Poland had to receive documents confirming their education status, indicating the class grade the student attended. Students in grades IV, VII and X were to receive certificates confirming their graduation. Teachers in schools for Polish children had to be provided with documents proving their work in the USSR detailing the number of hours of classes per week. He also asked that the local authorities allow students to take their textbooks and immediately send messages to the Committee about closing facilities.[13]

In order to ensure a smooth departure of single children and small groups to Poland, an Evacuation Orphanage was established based on an existing institution in Zagorsk (Moscow Oblast; today Sergeyev Posad). It was formed on October 15, 1945, on the basis of decision of the Sovnarkom USSR (No. 15083-r). The last group left this institution on July 30, 1946.[14]

I would like to add that it was a troublesome to find single children located in various institutions across the vast territory of USSR. To solve this, the Committee for Polish Children in the USSR established an Address Office. In addition, all institutions were called not to impose any obstacles and immediately issue passes to children sent to the Evacuation Orphanage in Zagorsk, on the basis of November 15, 1945 regulation of the Main Board of the NKVD Militia (decision No. 29 / Ja). The organization of an efficient repatriation action (e.g., ensuring the correct number of wagons) was possible thanks to the cooperation of ministries of education, finance, trade and communication. It was a huge undertaking and a logistical challenge. The impressive statistics reflected in the documents present very precise statements, regulations and messages which show the controlled nature of the Soviet state.

Regional and national departments received detailed nutrition standards for 1 pupil from the Committee. In addition, children’s institutions could collect products that they received from the Uprosobtorg[15] (Głowacki, Ocalić i repatriować 239–243).

The documents stated that each child was entitled to 10 rubles covering a hot lunch for each day of travel.[16]

Financial standards have been established for each group, allocating from 5,000 to 10,000 rubles for extra expenses. A group would consist of 140 children and 15 accompanying staff. Depending on the duration of travel (in days), the following amounts were declared per 1 student: for 20 days of travel – 1,622 rubles, for 15 days of travel – 1,444 rubles, for 10 days of travel – 1,276 rubles.[17]

On November 11, 1945, Poland and the USSR agreed to extend the deadline for changing citizenship (until January 1, 1946) and to complete repatriation until June 15, 1946. The agreement of July 6, 1945 was also slightly changed. This foregoing amendments were based on a decree of the Presidium of the Council Highest in the USSR.

In December 1945, Koniachina sent a letter to Danyło Byczenka (Head of the Resettlement Board at the Sovnarkom of the USSR), in which she presented a schedule for the departure of Polish children from the USSR to Poland. The number of children and accompanying staff were determined based on data prepared on October 1, 1945. First, children from orphanages in Zagorsk and Chkalov were to depart (January 20, 1946). Worth mentioning is that part of the building in Chkalov was destroyed by fire, resulting in difficult living conditions. The departure date for remaining establishments was set for April 1, 1946. The premise that guided the planned timeline was the geographical distribution of individual establishments, the end of the school year and timely delivery of passenger carriages (only these factors were mentioned in the foregoing letter).[18]

On January 1, 1946, precise statistics were prepared by the Committee as a result of Regulation No. 817 issued on October 1, 1945 by the Sovnarkom of the USSR. They confirmed the existence of 52 orphanages for Polish children and 7 additional branches at Russian facilities, sheltering 4,840 children.

Ultimately, 5,269 children went to Poland, which was ultimately 429 children more than the number planned in previously prepared schedules (60 orphanages).[19]

The Committee for Polish Children in the USSR employees systematically recorded all the undertakings and tasks carried out during the repatriation. Meeting the requirements meant hard and painstaking effort. According to the plan, orphanages located in the territory of the RSFSR were repatriated to Poland between March and April 1946, with the exception of institutions in Krasnoyarsk and Stavropol Krai, where repatriation began in February 1946. Orphanages from Tomsk, Vologodzk Oblasts and Udmurt ASSR were repatriated only in May due to difficult weather conditions and remote location far from railways. By April 3, 1946, 16 orphanages were repatriated from USSR to Poland, comprising of 1,562 pupils and 389 accompanying staff.[20]

The next stage of repatriation was planned for April, targeting pupils from orphanages in: the Kazakh SSR, the Kyrgyz SSR, the Tajik SSR (from April 18), the Uzbek SSR, the Altai Krai and the Gorky Oblasts (an institution in Kstov) and Sverdlovsk.

In May, institutions from the Chkalov, Irkutsk, Omsk, Tyumen and Voronezh Oblasts as well as from the Udmurt ASSR were resettled. In June, children from Tobolsk and Vologodzk Oblasts (orphanage in Babuszynsk) left.[21]

According to planned schedules, 729 children from the RSFSR (12 orphanages) were to be repatriated in April, May and June, and additionally 2,613 children from remaining republics (30 orphanages).[22] The latter included: 160 children from the Kyrgyz SSR (2 orphanages), 934 children from the Kazakh SSR (9 orphanages), 298 children from the Tajik SSR (3 orphanages) and 1,221 children from the Uzbek SSR (16 orphanages).

As of April 3, 1946, 1,563 children (from 16 orphanages) and 389 accompanying staff and teachers from connected schools were repatriated to Poland from oblasts located in the territory of the RSFSR. Among the passengers, were also pupils from an orphanage in Mukrynsk (Taldykorgan Oblast, Kazakh SSR), transported together with Polish citizens (58 children and 13 employees).[23]

During the Committee plenary session on May 4, 1946, its chairman (Novikov) presented the implementation plan to repatriate Polish children. Based on commitments discussed, he estimated the completion of the plan by June 15, 1946 (ultimately, the deadline was not met). He noted that the departure schedule was determined based on the distances from the nearest railway, river road and, most importantly, the geographical location of the institutions. Children from 30 orphanages were planned to return to Poland from Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan. He indicated that on May 1, 1946, a group of children left Kazakhstan on a special train. He discussed the preparations, plans and the course of repatriation, which had only begun in August 1945. At that time, the first letters were sent requesting detailed statistics of the pupils. Employees of the Committee for Polish Children in the USSR went on numerous delegations, during which they supervised the preparations and encouraged officials to provide necessary help.[24]

The costs of repatriation amounted to approx. 8 million rubles, with additional 0.5 million rubles after adding the costs of personnel.[25]

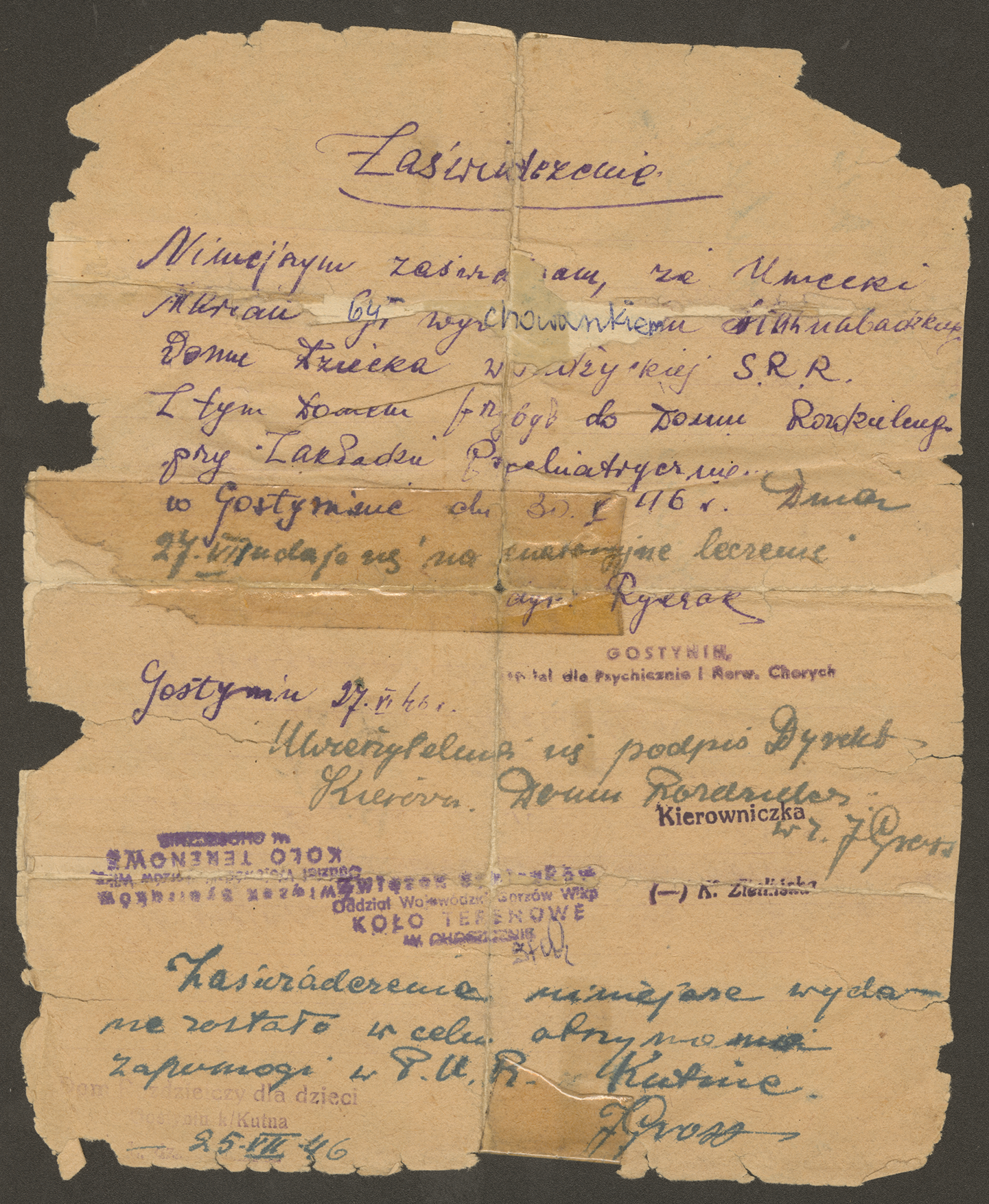

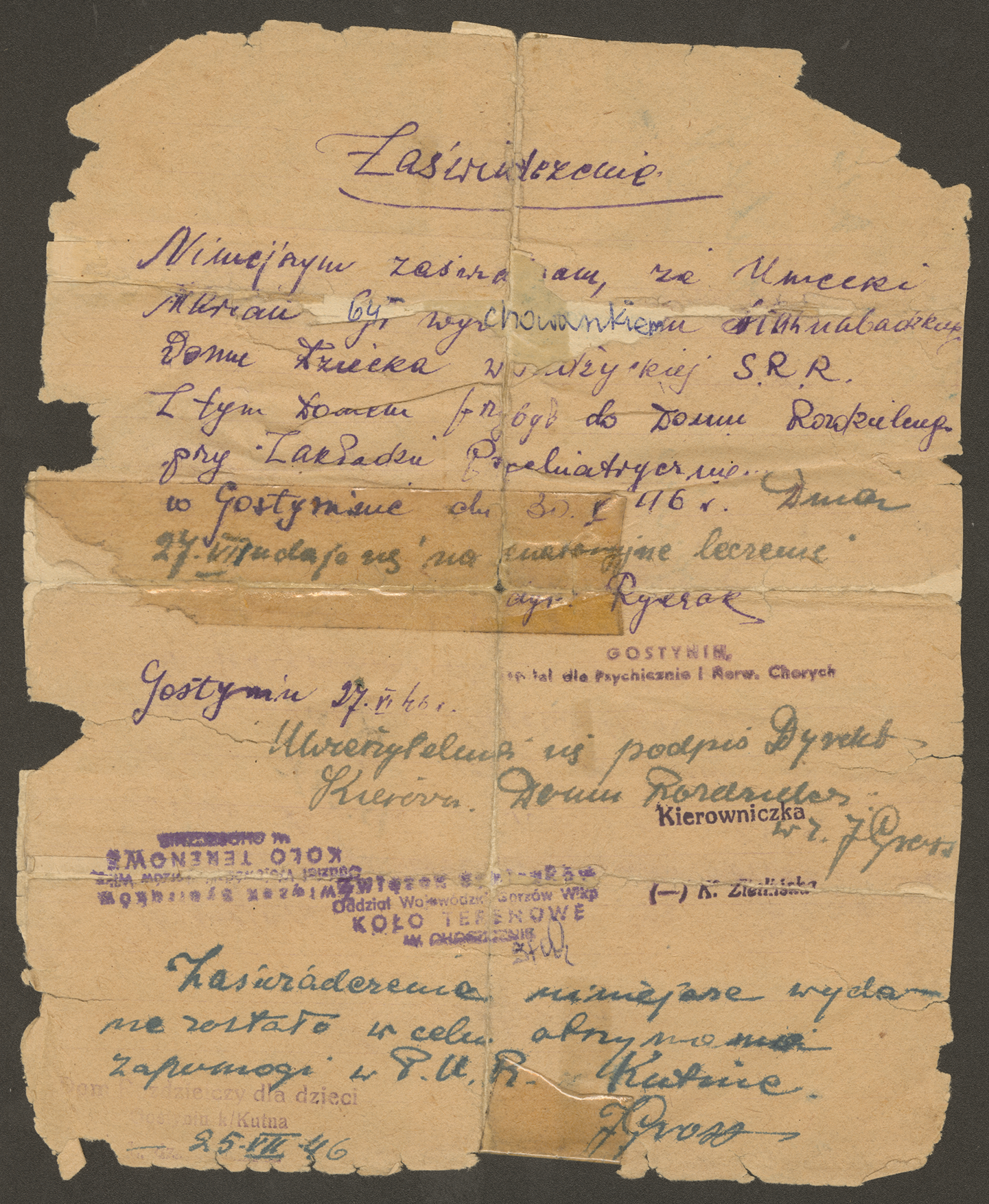

In March 1946, Polish ministries of education and health, decided to set up a Repatriation and Distribution House for repatriated children in vacant rooms of a >Hospital for Nervously and Mentally Ill in Gostynin. Transports with children were arriving there from March to August 1946 (Osmałek 553; Bugaj 137–40; Boćkowski, Repatriacja dzieci polskich 103; Marciniak 296; Konarska-Pabiniak, Dom Rozdzielczy 39; Dzienis-Todorczuk 238).

The director of the hospital, Dr. Eugeniusz Wilczkowski, was nominated to supervise the created facility[26] (Berner 21; Puś 18). In February 1946, the hospital had 250 available beds. On February 23, 1946, the director sent a report to the Ministry of Education in Warsaw noting that: “the preparation of a unit in the name of dr. K Mikulski (large brick) is in full swing. The beds are set up. Final minor refurbishments are underway. All kinds of purchases are made […]. In February, we received salt, sugar and marmalade as part of ‘guaranteed’ allocation for the hospital, and only paper for bread. We have absolutely no underwear for children. Older children will have to sleep in adult size shirts. We have enough beds, mattresses and baskets. The pillows will be made from straw. There are no pillowcases, but we may get them” (Konarska-Pabiniak, Dom Rozdzielczy 39; Konarska-Pabiniak, Dzieje gostynińskiej psychiatrii 40).

Katarzyna Zielińska became the head of the facility, doctor Helena Dreszerowa was the administrative and medical head and the hospital’s representative for repatriates. Medical care was provided by 8 doctors and 20 middle-class medical personnel. In addition, the following people were employed at the Repatriation and Distribution House: intendant – Chlewiński, secretary – Mikulska, Ciszewski, economic clerk – Matisow, field inspector – Stanisław Cichalewski, employees: Zygmunt Cichalewski, Lamecki, Dalecki. Staff of pavilion 3a: chief of staff – Dr. Dreszerowa, sister nurse – H. Sygulska, elder nurse – Stanisława Ciećwierz, senior ward staff – Oszczyk, ward staff – Włodarczyk, nurses: Kowalczyk, Fidrysiak, Ciechomski, cook – Kowalska, cook’s assistant – Wroczyńska, nurses – Fidrysiakówna, Zarzycka, Nowicka, Łuszczakówna, Imbirska, Pietraszkówna, Wałęsówna and German staff – Lidia Fobel, Lidia Bauer, Jedw. Heiser, Berła Himkelman (Osmałek 41; Konarska-Pabiniak, Dzieje gostynińskiej psychiatrii 41; Rękawiecki 92).

The first transport of 180 people (including 153 children) arrived in Gostynin on March 15, 1946 from Ipatov (Stavropol Krai). Another with 206 people arrived on March 23, 1945 from Stanica Apfiska (Krasnodar Krai) and Zagorsk. Between March 15–26, 1946, a total of 430 children from Stavropol, Krasnodar Krai and Zagorsk were admitted. Next, a transport with 150 children from Chkalov (today Orenburg) was planned to arrive. Over the next two weeks, children from six transports were received. In April, transports with children from the RSFSR arrived, in May and June there were children from institutions in Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan and Tajikistan, as well as from the most distant oblasts of the RSFSR (Rękawiecki, 2014: 92; Konarska-Pabiniak, Dzieje gostynińskiej psychiatrii 41; Bugaj 138).

Irena Bonadrowicz, deputy director of the orphanage in Atbasar, Kazakhstan, had written about the Psychiatric Center in Gostynin: “they took children from all orphanages from the USSR to the Hospital in Gostynin. It was a park area, filled with trees and huge multi-story buildings. We were placed in large halls.” (Kołodziejska-Fuentes 295).

Not all transports reached Gostynin. 78 children from the orphanage in Danilovka (Muraszynsk District, Kirov Oblast) and 70 children from the orphanage in Oparino (Kirovsk District) were sent directly to Zbąszyń. (Bugaj 138).

On March 18, 1946, director Wilczkowski, in a letter to the Headquarters of the State Repatriation Office in Łódź, noted that “the entire stock of hospital linen had been at the disposal of children, but there was no linen for change neither for the sick, nor for the children. Bearing in mind that, apart from mentally healthy children, the Hospital aimed to accept all transports with mentally ill repatriates, I kindly request that the Hospital be allocated complete equipment for 750 beds with necessary furnishing”.

In another letter sent three weeks later to the Ministry of Supply and Trade (April 11, 1946), Wilczkowski mentioned that the hospital had received “only some articles in very limited amounts absolutely not sufficient to feed the residing number of people” (Konarska-Pabiniak, Dom Rozdzielczy 39).

On June 1, 1946, it turned out that the debt of the Ministry of Education towards the hospital amounted to rubles 20,655.00, and “the hospital received only one food allowance (sugar 4 VI, canned meat 4 VI, barley groats 4 VI, wheat flour 13 VI, peas 22 VI, beans 22 VI, flour instead of bread 24 VI). No allocation received for potatoes, vegetables, fat, eggs” (Konarska-Pabiniak, Dom Rozdzielczy 39).

It was evident that funds were missing for the hospital’s day-to-day operations. In fact, an advance payment of rubles 600,000 was necessary. Wilczkowski reported in a special letter: “Higher cost of living was influenced by the increase in prices for food products, especially in April, and the special conditions of servicing the Distribution House, in particular the need to constantly disinfect repatriates’ belongings, requiring more opal and more technical personnel. Thus far, about 1,400 sets of repatriates’ clothes and linen, excluding hospital linen, had been disinfected, the laundry activities had been intensified, and the staff needed to handle them was constantly changing due to the flow of transports […]. The unpredictable arrival of transports, especially those without prior notice, forced the hiring of overtime personnel paid in accordance with the contract” (Konarska-Pabiniak, Dom Rozdzielczy 39).

The effects of the foregoing actions were nearly immediate. On June 24, 1946, the ministry began a meticulous inspection of the Repatriation and Distribution House, on the basis of numerous financial requests and expectations declared by director Wilczkowski. The reports post-inspection mentioned “educational care was equal to the task” and „the appearance of children was neat”. The feeding of children was carefully controlled by Dr. Anna Kulikowska (she was a senior head physician, and during her illness she was replaced by senior head physician Dr. Zimmerman). Only thanks to their efforts and precaution, children were provided the standard norm of nutrition (2400 cal.) as recommended by the Ministry of Health (Konarska-Pabiniak, Dom Rozdzielczy 40–41; Kulikowska 211).

According to studies, Children arriving from USSR to Gostynin “were extremely exhausted and infested by lice, suffered from mycosis, scarlet fever, and lung diseases”. They were immediately places at the hospital ward. Wilczkowski kept detailed statistics, where he recorded “June 1 – July 15, the list of diseases was as follows: malaria 194 cases, trachoma 8, mycosis 44, tuberculosis 30, various 68, i.e. mumps, flu, diarrhea, angina, scarlet fever, scabies. July 16 – August 1: malaria 16, angina 4, bone tuberculosis 2, pleuritis 1, fracture of the lower leg 2, pulmonary tuberculosis 2, otitis 2, icterus 1, pneumonia 1, scabies 3, bronchitis 3, mycosis 30” (Konarska-Pabiniak Dom Rozdzielczy 40; Rękawiecki 93).

Children with suspected trachoma[27] were sent to Treatment and Educational Institute of the Jagiellonian University in Witkowice near Kraków (Rączka 129–142). Currently, it is an Ophthalmology Hospital at ul. Osiedle na Wzgórzach 17 B in Kraków. Patients with tuberculosis were taken to sanatoriums in Busko, Rabsztyn and Istebna (Rękawiecki 93).

On July 24, 1946 Dr. Wilczkowski reported after the inspection of the Visiting Committee: “All hospital staff, on the one hand personnel managing: administration, technical tasks, kitchen duty, laundry, and on the other hand medical and nursing staff, went to great lengths to cope with the tasks assigned to them, oftentimes working long overtime hours. Obtaining products, even on the free market, was nearly impossible and always caused difficulties. Cyclists were sent out to buy potatoes, rye, peas, etc., and trucks were sent to transport the purchased products. On top of that, work nearly resembled difficult of the frontline: constant phone calls, noise produced by proprietary and rented cars rushing back and forth 5 km from the town of Gostynin, messengers moving around with various orders, endless work all day and often night across all sections (receiving, returning, counting, signing up, bathing, disinfecting, repairing of technical devices broken by children, carrying various things, etc.). All this with enormous cash difficulties, with delayed food allocations, and with a load two times larger than predicted for the hospital. Nevertheless, there was the ambition to fulfill the task and indeed it was achieved thanks to an extraordinary effort of the entire team that deserves recognition” (Konarska-Pabiniak, Dom Rozdzielczy 41).

On August 15, 1946, the Repatriation and Distribution House for children repatriated from the USSR was dissolved. On September 20, 1946, the hospital management received thanks from the Ministry of Education, signed by the deputy director of the department, F. Borkowski. Recognition and appreciation was given to the Management of the Hospital for Mentally and Nervously Ill in Gostynin, which contributed greatly by managing the economic and administrative side of the undertaking. The minister expressed gratitude through the Hospital’s Board towards all Hospital employees who put great work and effort into the tasks of the Distribution House in Gostynin. (Konarska-Pabiniak, Dom Rozdzielczy 41).

The children stayed in the Repatriation and Distribution House between 10 to 15 days. Then they were sent to other institutions. Children from Tashkent went to an orphanage in Helenówek near Łódź. The rest were sent to other orphanages or care-giving institutions in: Wrocław, Ząbkowice Śląskie, Malbork, Bytów, Sztum, Toruń, Słupsk, Wrzeszcz, Sopot and Leszno[28] (Konarska-Pabiniak, Dom Rozdzielczy 40; Osmałek 554).

In the perfectly preserved, beautiful cardboard Memorial Book of the Hospital for Mentally and Nervously Ill in Gostynin, one may find photographs, drawings and handwritten, beautifully calligraphed entries of children and caregivers from orphanages in Shwarycha (Gorky Oblast), Stavropol (Kuybyshev District), Nizna Uwelka (Chelyabinsk Oblast), Bolshaya Jerba, Porog and Mala Minusa (Krasnoyarsk Krai), Ipatov (Stavropol Krai), Aktiubinsk,[29] Ush-Tobe and Turkestan (Kazakh SSR). They confirm excellent care, kindness, and include words of appreciation towards the staff of the center. Many warm words were also addressed to Priest Prelate Helenowski.[30]

A very cordial entry from the pupils and staff of the children’s home in Shwarycha (April 22, 1946) expresses the words of appreciation for the care received: “Gostynin, Repatriation House for Children, made a strong, impression and will remain forever in the memory and in the hearts of children and adults who were lucky to stay here when returning from Russia. Words are not enough to express everything that was felt in the hearts of the children of the Children’s Home from Shwarycha, Gorky Oblast and the employees of this house, when after 6 years of wandering, the Homeland welcomed them in the best way it could with a warm and pure Polish heart”.[31]

Another souvenir is the entry from April 30, 1946 from people returning from Mala Minusa, who noted: “We found ourselves here in Gostynin, a Distribution House for children, as if in a real oasis! Among green forests, beautiful paths, there are breathtaking houses in the light of the setting sun, but the souls of people who reside here are a hundred times more beautiful. They, like parents, sisters and brothers, approached us with a good word and golden consolation, and we felt as if the whole time apart we were with them!”.[32]

On August 6, 1946, the Ministry of Education of the RSFSR sent a letter (No. 974) to the Deputy Chairman of the Council of Ministers of the USSR (Lavrentiy Beria), informing him that the tasks imposed on the Committee in the resolution of June 30, 1943 had been completed. 5,269 foster children had left for Poland (60 orphanages). In total, 18,869 students and 3,080 preschoolers returned to their homeland with their parents or relatives. The property owned by educational institutions had been put at the disposal of local education ministries.[33]

On September 18, 1946 in Moscow, on the basis of the regulation of the Council of Ministers of the USSR (No. 11,267-r), the Committee for Polish Children in the USSR was dissolved.[34]

Table 1. The number of workers accompanying Polish children during their journey from the USSR to Poland (1946).

| Position | Train with 50–60 children | Train with 100–120 children | Train with 150–160 children | Train with 200–250 children | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Train manager | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 2 | Economic manager (authorizing officer) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 3 | Medical staff (doctor or nurse) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 4 | Educators | 2 | 4 | 6 | 8 |

| 5 | Support staff | 3 | 4 | 5 | 7 |

| 8 | 11 | 14 | 18 |

Note: The train manager, economic manager and medical staff were not employees of orphanages. After bringing the children to the border, they returned to the USSR. The remaining people were to be selected from among the employees of care institutions, first of all from the group of people subject to repatriation to Poland.

Source: GARF, sign. A-304-1-141, p. 62.

Translation of the Introduction by Jacek T. Waliński

Translation by Ewa Granosik

Berner, J. “Akademicka droga łódzkiej medycyny.” Forum Bibliotek Medycznych 1.11 (2013): 21.

Boćkowski, D. Dyplomacja Rządu Drugiej Rzeczypospolitej na uchodźstwie wobec kwestii polskiej w ZSRR w latach 1939–1945. Ed. J. Faryś, M. Szczerbiński, Z dziejów polskiej służby dyplomatycznej i konsularnej. Księga upamiętniająca życie i dzieło Jana Nowaka-Jeziorańskiego. Gorzów Wielkopolski: Sonar, 2005.

Boćkowski, D. “Repatriacja dzieci polskich z głębi ZSRR w latach 1945–52.” Studia z Dziejów Rosji i Europy Środkowo-Wschodniej 29 (1994): 99–108.

Bugaj, T. Dzieci polskie w ZSRR i ich repatriacja 1939–1952. Jelenia Góra: Karkono-skie Towarzystwo Naukowe, 1982.

Ciesielski, S. Polacy w Kazachstanie 1940–1946. Zesłańcy lat wojny. Wrocław: Oficyna Artystyczno-Wydawnicza „W kolorach tęczy”, 1996.

Ciesielski, S., Hryciuk, G., Srebrakowski, A. Masowe deportacje ludności w Związku Radzieckim. Toruń: Wydawnictwo Adam Marszałek, 2004.

Czapski, J. Na nieludzkiej ziemi. Posłowie Lebiediewa, N.S. Kraków 2017.

Dokumenty i materiały do historii stosunków polsko-radzieckich, t. VII. Styczeń 1939–grudzień 1943. Warszawa 1973.

Dokumenty i materiały do historii stosunków polsko-radzieckich, t. VIII, Styczeń 1944–grudzień 1945. Warszawa 1974.

Dzienis-Todorczuk, M. Już w Polsce… Dom Rozdzielczy dla dzieci z repatriacji w Gostyninie i problem liczby polskich sierot wracających z zesłania w 1946 r. Eds. J. Kita, W. Marciniak, Losy Polaków na Wschodzie XIX–XX w. Repatriacje, przesiedlenia i osadnictwo. Łódź: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Łódzkiego, 2020.

Głowacki, A. Na pomoc zesłańczej edukacji. Działalność wydawnicza Komitetu do spraw Dzieci Polskich w ZSRR (1943–1946), wyd. II. Łódź: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Łódzkiego, 2019.

Głowacki, A. Ocalić i repatriować. Opieka nad ludnością polską w głębi terytorium ZSRR (1943–1946). Łódź: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Łódzkiego, 1994.

Głowacki, A. “Problem repatriacji wychowanków polskich domów dziecka z ZSRR (1945–1946).” My, Sybiracy 15 (2004): 34.

Historia dyplomacji polskiej, t. V, 1939–1945. Ed. W. Michowicz. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN, 1999.

Jonkajtys-Luba, G. Opowieść o 2 Korpusie Polskim generała Władysława Andersa. 60 rocznica bitwy o Monte Cassino. Warszawa: Stowarzyszenie Weteranów Armii Polskiej w Ameryce: Oficyna Wydawnicza Rytm, 2004.

“Komitet do spraw polskich dzieci w ZSRR.” Wolna Polska 19 (1943): 4.

“Komunikaty Zarządu Głównego Związku Patrjotów Polskich.” Wolna Polska 18 (1943): 4.

Konarska-Pabiniak, B. “Dom Rozdzielczy dla dzieci repatriowanych w Gostyninie.” Notatki Płockie Vol. 37, 4.151 (1992): 39–40.

Konarska-Pabiniak, B. “Dzieje gostynińskiej psychiatrii – w 70. rocznicę narodzin.” Notatki Płockie Vol. 49, 1.198 (2004): 40–41.

Kormanowa, Ż. Ludzie i życie. Warszawa: Książka i Wiedza, 1982.

Kuczyński, A. 400 lat polskiej diaspory. Zesłania, martyrologia i sukces cywilizacyjny. Rys historyczny. Antologia. Krzeszowice: Wydawnictwo „Kubajak”, 2007.

Kulikowska, A. “Okupacyjne wspomnienia ze Szpitala Psychiatrycznego w Gostyninie.” Przegląd Lekarski. Organ Polskiego Oddziału Polskiego Towarzystwa Lekarskiego, Vol. XXXIV, 1 (1977): 211.

Ladorucka, L. Komitet do spraw Dzieci Polskich w ZSRR 1943–1946. Ed. E. Kowalczyk, K. Rokicki. W drodze do władzy. Struktury komunistyczne realizujące politykę Rosji Sowieckiej i ZSRS wobec Polski (1917–1945). Warszawa, 2019.

Marciniak, W.F. Powroty z Sybiru. Repatriacja obywateli polskich z głębi ZSRR w latach 1945–1947. Łódź: Księży Młyn Dom Wydawniczy, 2014.

Materski, W. Na widecie. II Rzeczpospolita wobec Sowietów 1918–1943. Warszawa: Instytut Studiów Politycznych Polskiej Akademii Nauk, 2005.

Museum of Independence Traditions in Łódź, sign. A-9476, pp. 1–15.

Oppman, R., Wroński, B., Englert, J.L. Generał Sikorski. Premier, Naczelny Wódz. Prime Minister. Commander in Chief, wyd. II. Londyn–Warszawa: Polish Institute and Sikorski Museum in London, 2003.

Osmałek, M. Gostynin w latach 1945–1989. Ed. B. Konarska-Pabiniak. Dzieje Gostynina od XI do XXI wieku. Gostynin: Miejska Biblioteka Publiczna im. Jakuba z Gostynina, 2010.

Przerwane biografie. Relacje deportowanych z Polski w głąb Sowietów 1940–41, chosen by Ewa Kołodziejska-Fuentes. Warszawa: Ośrodek Karta & Centrum Polsko-Rosyjskiego Dialogu i Porozumienia, 2020.

“Przyjazd Karakulińskiego Domu Dziecka do Białegostoku.” Wolna Polska 23–24 (1945): 1.

Puś, W. Zarys historii Uniwersytetu Łódzkiego. Łódź: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Łódzkiego, 2015.

Rączka, J. W. “Zakład Leczniczo-Wychowawczy UJ w Witkowicach pod Krakowem.” Folia Historica Cracoviensia 6 (1999): 129–142. https://doi.org/10.15633/fhc.1415

Rękawiecki, R. “Dom Repatriacyjno-Rozdzielczy w Gostyninie-Zalesiu.” Nasze Korzenie: Półrocznik popularnonaukowy Muzeum Mazowieckiego w Płocku poświęcony przyrodzie, historii i kulturze północno-zachodniego Mazowsza 7 (2014): 92–93.

Rutkowski, T. P. Stanisław Kot 1885–1975. Biografia polityczna. Warszawa: DIG, 2000.

Siemaszko, Z. S. W sowieckim osaczeniu. 1939–1945. Londyn: Polska Fundacja Kulturalna, 1991.

Sprawa polska w czasie drugiej wojny światowej na arenie międzynarodowej. Zbiór dokumentów. Ed. S. Stanisławska. Warszawa: PWN, 1965.

Sprawozdanie z działalności Ambasady R.P. za okres od 7.VIII.1941 do 6.V.1943. Instytut Polski i Muzeum im. gen. Sikorskiego w Londynie, sign. A.7.307/38.

Syzdek, E. Działalność Wandy Wasilewskiej w latach drugiej wojny światowej. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Ministerstwa Obrony Narodowej, 1981.

Szkolnictwo polskie w ZSRR 1943–1947. Dokumenty i materiały. Comp. R. Polny, Ed. S. Skrzeszewski. Warszawa: Państwowe Zakłady Wydawnictw Szkolnych, 1961.

Szubtarska, B. Ambasada polska w ZSRR w latach 1941–1943. Warszawa: DIG, 2005.

The State Archive of the Russian Federation (GARF)

Trela, E. Edukacja dzieci polskich w Związku Radzieckim w latach 1941–1946. Warszawa: PWN, 1983.

Udzielona pomoc i opieka nad ludnością żydowską w ZSRR. Instytut Polski i Mu-zeum im. gen. Sikorskiego w Londynie, sign. A.7.307/40.

Wolna Polska 15 (1943): 4.

“Wychowankowie Domu Dziecka w Karakulino opuszczają gościnną ziemię radziecką.” Wolna Polska 20 (1945): 1.

Z dziejów Polaków w Kazachstanie 1936–1956. Zbiór dokumentów Prezydenta Republiki Kazachstanu. Ed. E.M. Gribanova et al. Warszawa: Oficyna Olszynka, 2006.

Żaroń, P. Kierunek wschodni w strategii wojskowo-politycznej gen. Władysława Sikorskiego. Warszawa: PWN, 1988.

Żaroń, P. Ludność polska w Związku Radzieckim w czasie II wojny światowej. Warszawa: PWN, 1990.

Żeglicki, T. “Szlakiem wychowanków Domu Dziecka w Karakulino.” Wolna Polska 8–9 (1945): 5.