Abstract. The tourism industry has drastically reduced its activity since the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic, yet there has been an undeniable rise in demand for wellness tourism which now represents one of the fastest growing tourism market segments globally. Admittedly, while the COVID-19 pandemic has delayed the forecasted wellness tourism growth trend, this segment has stood fast at USD 4.4 trillion in 2020 while global GDP declined by 2.8%. In 2020, the wellness tourism market was valued at USD 436 billion, projected to rise to USD 816 billion by 2022 with more than 1.2 billion trips being realised and anticipated growth estimated at USD 1.0trillion by 2025. The main purpose of this study is to ascertain the future trends of wellness tourism, and to investigate the extent to which this upward growth trend can be sustainably maintained post COVID-19. A qualitative structured interview methodology was employed using email interviews comprising six pre-determined questions with three expert wellness tourism participants. These expert interviewees were based in countries that were severely impacted by COVID-19, namely Brazil, USA, and Portugal. NVivo Nudist was used to analyse the primary data collected. In validating previous research findings, this study indicates that despite the challenges facing the sector, upward growth patterns in wellness tourism will continue beyond the COVID-19 pandemic.

Key words: wellness, wellness tourism, trends, COVID-19 pandemic.

The appearance of a new lethal disease, COVID-19, resulted in a combined health and financial crisis globally. This has been especially apparent in the tourism industry where COVID-19 continues to be a major disruption with potential far-reaching economic and psychological consequences and as the progress of the virus as yet unknown (Lew et al., 2020; Orîndaru et al., 2021). Consequently, the tourism industry has drastically reduced its activity and as Rahman et al. (2021) and Rokni (2021) contend tourist behaviour and mental well-being continue to be adversely affected by the pandemic. During such epidemics, the number of people whose mental health is affected tends to be greater than the number of people affected by the infection itself (Reardon, 2015; Shigemura et al., 2020). While tourism is one of the world’s largest industries it is also one of the most fragile ones vulnerable to crises and uncertainty. Despite such challenges, the tourism industry is preparing for recovery post COVID-19 (Sibi et al., 2020) with wellness tourism pivotal to this recovery (Majeed and Ramkissoon, 2020). Wellness tourism is considered one of the most rapidly advancing tourism segments globally and is expected to grow exponentially post COVID-19 (Mohan and Lamba, 2021).

Collectively, the tourism and wellness industries make a valuable contribution to both the global economy and social and cultural advancement. Wellness and wellness tourism are not new concepts with the search for self-care increasing following the imposed lockdown periods that affected almost all countries in the world. It is unsurprising, therefore, that wellness tourism is an expanding segment worldwide with the Global Wellness Institute (GWI, 2021) reporting that the wellness industry reached pre-pandemic levels recording up to USD 4.3 trillion in 2017 and USD 4.9 trillion in 2019. Following the COVID-19 outbreak, the global wellness economy declined by 11% to USD 4.4 trillion in 2020, yet the GWI (2021) predicted that global wellness will return to pre-pandemic values in 2021 and will grow by 10% annually until 2025. In the GWI’s (2021) ‘Global Wellness Economy: Looking Beyond COVID’ report, the wellness travel market is projected to reach almost USD1 trillion in 2020 representing 20% of global tourism and will grow by 7.5% annually by 2022. This forecasted trend is especially impactful to the tourism industry given that wellness tourists are typically higher spenders than most other tourists (GWI, 2018). For example, in 2017, international wellness tourists spent on average USD 1,528 per trip which was 53% more than the average international tourist. The premium for domestic wellness tourists was even higher, at USD 609 per trip which was 178% more than the typical domestic tourist (Global Wellness Institute, 2018). Overall, wellness tourism accounted for 830 million international and domestic visits in 2017, representing 17% of all tourism trips.

The current COVID-19 pandemic has enabled every destination to reflect, and assess strategies and propose new approaches to strengthen their wellness tourism offerings (Mohan and Lamba, 2021). This has stimulated new and emerging markets such as Asia, Latin America, and North Africa which according to the Global Wellness Institute (2021) will continue to experience rapid growth and expansion in this segment.

This present study contributes to the existing literature by considering the impact of COVID-19 on the future of wellness tourism with a particular focus on the extent to which the current upward trend in wellness tourism can be maintained. By investigating future wellness tourism trends, it is anticipated that this study will be of interest to policy makers, wellness tourism providers, tourism agencies, developers, and academic researchers.

Historically, the concept of wellness included the body, mind, spirit, and the environment associated with disease prevention, health well-being and happiness (Dunn, 1959). More recently, Laing and Weiler (2008) have observed that wellness is a holistic view of human life reflecting a physical and psychological peaceful mindset. According to Nahrstedt (2008), the definition of wellness echoes the World Health Organization’s search for well-being with the concept of “fitness.” As such, well-being involves much more than the physical, rather it is a quest to balance different aspects of life with historical, cultural, and linguistic differences influencing the interpretations of health and wellness. For example, in Hebrew, the term wellness is translated as health, yet health and wellness are not interchangeable terms. Myers et al. (2000) defined wellness as a way of life guided by the pursuit of health and well-being, bringing together the body, mind, and spirit. Similarly, Muller and Kaufmann (2000) have agreed that wellness is the sum of elements merging harmony with the body, mind, spirit, self-responsibility, physical activities, beauty care, nutritional health, relaxation, meditation, mental activity, education, sensitivity to the environment, and social contacts. Therefore, wellness is associated with psychological (behaviour, emotional, and cognitive) aspects rather than physical aspects alone. In agreement with Muller and Kaufmann (2000, p.7):

“Wellness tourism is the sum of all the relationships and phenomena resulting from a journey and residence by people whose main motive is to preserve or promote their health. They stay in a specialized hotel which provides the appropriate professional know-how and individual care. They require a comprehensive service package comprising physical fitness/ beauty care, healthy nutrition/ diet, relaxation/ meditation, and mental activity/ education.”

Adams (2003) extended this definition in referring to four wellness principles: a) Wellness is multi-dimensional; b) the practice of Wellness must be guided, seeking the causes of wellness and not diseases; c) Wellness is about balance; d) Wellness is relative, subjective, and perceptive. In addition, Adams (2003) has recognised that wellness is composed of at least six components in his proposed wellness model which includes emotional, intellectual, psychological, physical, spiritual, and social components. More recently, GWI (2020) defined wellness as an active pursuit of lifestyle choices that in turn leads to a state of holistic health. As with many definitions of wellness, the GWI has stressed that wellness is individual given that one person’s wellness may be another person’s stress. Evidence suggests that wellness is much more than physical health, rather it incorporates a series of dimensions that have the potential to work together to create harmony and happiness (Global Wellness Institute, 2020). Reflecting Adams (2003), the GWI has recognised that wellness includes dimensions of the physical, mental, spiritual, emotional, social, and environmental. These dimensions suggest that wellness strives to create harmony through mental, physical, spiritual, and biological health and it is the GWI’s (2020) definition of wellness which guides this study.

Ryan (1997) has contended that tourism has always been a process of self-regeneration, relaxation, education, and indulgence while Seaton and Bennett (1996) have suggested that the psychological and physical effects of tourism are increasingly significant. More recently, emphasis has been placed more on the mind than on the physical, and while people continue to travel for the purposes of physical health and fitness, the pursuit of relaxation and wellness dominates (Koncul, 2012). In response to this growing demand, countries, medical providers, and hospitality and tourism organisations are adapting to offer a broader set of wellness tourism experiences. Unsurprisingly, there is consensus that wellness is not just about the physical, but rather that wellness relates to a desire to feel complete, to take care of the mind and to feel good about oneself, even though wellness activities are predominantly physical, such as thermal water therapies, detoxification, yoga, and massage treatments. Thus, wellness as Adams (2003) has suggested is relative, subjective, perceptual, and multi-dimensional, and is impacting the growth of wellness tourism with the holistic concept of wellness tourism draws together health, wellbeing, hospitality, and transportation to deliver numerous tourists services. According to Voigt and Pforr (2013) increases in human stress have expanded demand for more personalised services while the ageing of populations predisposes the further development of wellness tourism.

Lounsbury and Hoops (1986) claimed there was a positive correlation between travel, health, and wellbeing. More specifically, satisfying travel, relaxation, escape, marriage and family, food, and accommodation needs through travel experiences can contribute significantly to human well-being (Lounsbury and Hoopes, 1986; Neal et al., 2007) with such benefits felt before, during, and after the travel experience.

The GWI (2018) has suggested that wellness tourists consist of people who already have a healthy lifestyle and seek to maintain or improve their wellbeing with wellness tourism understood as one of the many layers of health tourism (Chen et al., 2007; Global Wellness Institute, 2018; Medina-Muñoz and Medina-Muñoz, 2013; Voigt et al., 2011). Thus, wellness tourism is a combination of concepts encompassing spirituality, hedonism, escapism, relaxation, lifestyle, intellectual, socialisation, the physical, and the mind (Smith and Puczkó, 2009). Mueller and Kaufman’s (2001) definition of wellness tourism as activities associated with traveling to improve physical, mental and social health and promote well-being echoes Smith and Puczkó’s (2009) understanding of wellness tourism. Voigt et al. (2011) and Dillette et al. (2020) have included specific wellness places and activities while Ellis (2013) referred to:

People searching for wellness products tend to have a higher sociocultural and economic status than conventional tourists as observed by the GWI (2021) report proposing there are two types of wellness tourists. Primary wellness travellers are motivated to travel or choose their destination based on the wellness activities offered (such as a wellness resort or participating in a yoga retreat), while secondary wellness travellers are those seeking to maintain their well-being or participate in wellness activities such as going to the gym, receiving a massage, and prioritising healthy eating when traveling.

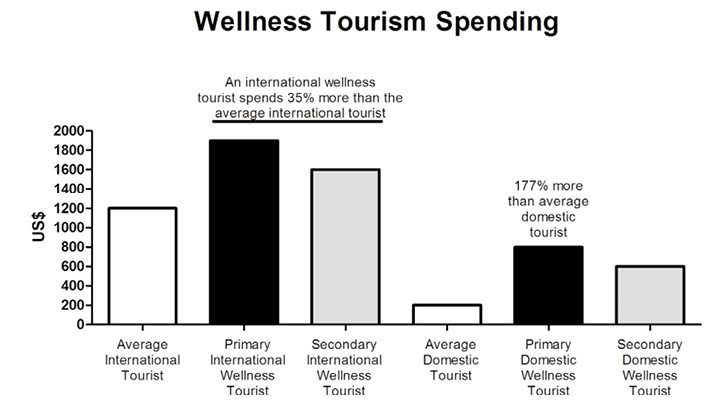

As indicated in Fig. 1, the secondary tourist comprised 89% of wellness tourism trips and 86% of tourist spending in 2020 with greatest growth anticipated in this tourist profile. The domestic traveller accounts for 82% of wellness tourism and 65% of tourist spending with an expected growth of 9% per year. Given the increased transport and accommodation costs for international travel, the highest spending is most likely for the international wellness tourist with an anticipated growth rate of 12%. Collectively, therefore, wellness travellers spend more than traditional tourists, both domestically and internationally. In 2020, international wellness tourists spent an average of USD 1,601.00 per trip, 35% more than the traditional tourist while the domestic tourists’ average spending was USD 609.00 per trip. As such, wellness travellers are typically more affluent and educated, tend to be early adopters, and they frequently engage in new and more novel experiences (Global Wellness Institute, 2021). Interestingly, Deesilatham (2016) has observed that women are the most likely wellness tourists supporting Puczkó and Bachvarov’s (2006) previous study which contended that women under 30 years of age dominated in this segment. Similarly, both Smith and Puczkó’s (2014) study and an extensive report undertaken by Spafinder Wellness Travel (2015) commented that Gen x (36–45) and baby boomers (46–65) were the top two consumer groups most likely to book wellness holidays. Both studies agreed that wellness tourists were typically consumers under the age 49, had high-incomes, were well-educated and sought new experiences, pampering, lifestyle, and luxury wellness services.

Fig. 1. Wellness Tourism Spending Premiums (2020)

Source: adapted from The Global Wellness Economy: Looking Beyond COVID (Global Wellness Institute, 2021).

Studies indicate that the COVID-19 pandemic has negatively impacted quality of life for younger people in particular citing confinement during lockdown leading to a significant rise in mental illness including anxiety, irritability, depression, and other mood disorders (Anseret al., 2021; Sahoo et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020; Ahorsu et al., 2020; Õri et al., 2021). While young people engaged with digital technologies for long periods pre-COVID-19, isolation and imposed confinement resulting from COVID-19 intensified young people’s tendency to consume social media. This has exacerbated anxiety and unhappy mood levels among young people (Gudiño et al., 2022; Mustafa et al., 2020). In addition, Duan et al. (2020) have suggested that during the COVID-19 pandemic young people were typically engaging in physical exercise less than once a week while their intake of soft drinks and junk food increased significantly.

According to the GWI (2021) the top five wellness countries include the United States, Germany, China, France, and Japan. In addition, destinations with a long association with traditional wellness lifestyles are gaining significant momentum in attracting wellness tourists as illustrated in Table 1.

| Country | Rank in 2020 |

Wellness Tourism Expenditures (USD billions) |

Number of trips (millions) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | 2019 | 2020 | 2020 | ||

| United States | 1 | 226 | 263.5 | 162.1 | 114.8 |

| Germany | 2 | 65.7 | 73.5 | 59.0 | 57.4 |

| France | 3 | 30.7 | 34.7 | 21.3 | 21.8 |

| China | 4 | 26.4 | 34.4 | 19.5 | 67.5 |

| Japan | 5 | 23.9 | 26.6 | 19.1 | 33.8 |

| Austria | 6 | 16.5 | 18.9 | 11.9 | 13.1 |

| Switzerland | 7 | 13.4 | 15.5 | 10.8 | 8.4 |

| Italy | 8 | 13.4 | 14.5 | 9.0 | 8.6 |

| United Kingdom | 9 | 13.5 | 15.1 | 9.0 | 16.4 |

| Australia | 10 | 12.3 | 14.0 | 8.5 | 8.6 |

| Canada | 11 | 12.5 | 13.9 | 8.4 | 10.0 |

| India | 12 | 11.4 | 13.3 | 7.2 | 48.2 |

| Mexico | 13 | 9.7 | 12.5 | 6.2 | 11.9 |

| Spain | 14 | 9.9 | 10.8 | 5.2 | 12.7 |

| Thailand | 15 | 12.0 | 16.9 | 4.7 | 6.5 |

| South Korea | 16 | 6.8 | 8.3 | 4.3 | 16.8 |

| Malaysia | 17 | 5.0 | 6.1 | 3.5 | 7.5 |

| Portugal | 18 | 3.4 | 4.4 | 2.8 | 4.0 |

| Denmark | 19 | 3.2 | 3.8 | 2.8 | 6.6 |

| Turkey | 20 | 4.5 | 5.7 | 2.7 | 6.7 |

Wellness tourism research focuses on benefiting community development, rural places, and green areas such as national parks (Bell et al., 2015) which is reflective of the market segment. For example, airports and airlines are promoting wellness programmes such as Fly Healthy and Fly Well, while the provision of such services as spas at airports and gyms, meditations on the flights, healthy catering, and clean design at airports are evident. Such a partnership between wellness companies and travel brands seeks to harness routine consumer wellness habits while travelling to leverage wellness trends, as the collaboration between Peloton and Westin Hotels, Intrepid travel and tours offering, and the birth of micro trips (Law, 2022) demonstrate. According to Smith and Puczkó (2009), the tourism industry is harnessing what Law (2022) declared as a ‘wellness boom’ in several ways including:

a) Hotels (clean and healthy hotels) incorporating clean aesthetics, healthy, natural, and organic foods, and activities to provide a calm and relaxing atmosphere for the guests through biophilic design. Such design is a philosophy that encourages the use of natural systems and processes in the process to build the environment (Kellert et al., 2008) based on the Biophilia hypothesis. This hypothesis proposes that humans have an innate connection with the natural world (Wilson, 1984) and that exposure to the natural world is, therefore, important for human wellbeing.

b) Building the connection between travel, work, and wellness with coworking becoming very common because of the COVID-19 pandemic. People are travelling more and working at the same time demonstrating that a person can live, work and experience new cultures while maintaining wellness in any location.

c) Blending traditional hospitals with spas to offer medical treatments and spa services for a more holistic experience. As Smith and Puczkó (2009) have argued, Wellpitals and Medhotels offer the blended services and qualities of hospitals, hotels and spas without the hospital, clinic or standard hotel image or feel becoming either an extended spa, adapted hospital or cruise ship which is a blend between hospitals and spas, that offers medical treatments and spa services (Wellness Tourism Worldwide WTW, 2020).

d) Offering Spa Living Environments (Navarrete and Shaw, 2021) and EcoFit Resorts/Eco-Friendly Resorts (Smith and Puczkó,2009) to provide spaces to relax and improve physical and physiological health through comfortable pet-friendly or natural surroundings. Such places include outdoor activities, massages, yoga, natural and organic foods, and physical activity facilities.

e) Developing dreamscapes, which are luxury products targeted at younger age groups, offering futuristic experience, like a cinema in a spa, with music, and games to induce another world feeling.

f) Designing well-working environments to create a calm and relaxed space for employees through the provision of workplace gyms, healthy food options and medical incentive travel opportunities.

In agreement with Law (2022) this study recognises that there is a wide range of available wellness tourism assets reflected in the diverse and creative offerings available across the world. However, while diverse wellness tourism services and products are available across the globe reflecting increasing consumer demand, such services and products are not universally consumed or accessed in the same way. Therefore, this study contends that new wellness tourism strategies are required to assist in the recovery of the global tourism industry post the COVID-19 outbreak. Given that 56% of people prioritise their well-being while 42% will seek wellness travel options following the COVID-19 pandemic according to GWI (2021), a new era of wellness tourism is unfolding. However, as noted by the WTW (2020, p. 41) a major threat to this upward growth trend is the anticipated ‘globalization of standardized and uniform products and services which can only serve to undermine uniqueness and competitiveness.’

Existing literature suggests that customising the wellness tourist’s experience is necessary due to the standard protocols imposed to curb the spread of the virus and to fulfil consumers’ need for a more bespoke consumer experience. Indications suggest that a combination of maintaining the availability of wellness assets and enhancing product diversification through the creation of new luxury and more personalised wellness services to ensure sustainable future growth is the key to the future development of wellness tourism.

To extend this line of enquiry, primary research was conducted using a qualitative research approach employing three structured email interviews with representative experts to further discovery of anticipated wellness tourism trends. Email interviews were considered an appropriate data collection instrument based on an assessment of the research aim, confidence of credible findings, ease of accessibility, and the subject population’s familiarisation with the technology. Notwithstanding the small sample size this approach can produce a substantial amount of data (Jones and Gratton, 2010), promotes a deeper investigation, and allows the researchers to focus on the context of the information gathered whilst also gaining a broad understanding of it (Pechlaner and Volgger, 2012). As Meho (2006) has agreed, email interviews give respondents time to answer questions at their own pace over an extended period while Ratislavová and Ratislav (2014) have advised that email interviewing provides extended access to participants compared to other types of interviews so interviewees can better formulate answers without disruption. Access during the pandemic was particularly relevant in this study. The interviewees included a Vice President of a Wellness Association in Portugal, a Chair of a Wellness Institute in the United States, and a Wellness Hotel Marketing Supervisor in Brazil. These interview exchanges occurred between May and July 2021, a time when the impact of COVID-19 on the tourism industry was severe in all three destinations. The back-and-forth email conversations allowed for prolonged engagement with participants to connect and establish relationships, enabled the researchers to clarify descriptive data, pursue further discovery, and ensure accuracy in describing wellness tourism trends from the perspective of the interviewees. To maintain discretion respondents’ names were coded. A content analysis approach was employed to systematically describe the content of each email message as advised by Bardin (1977), and Franco (2008). Data input and analysis was conducted using the NVivo Nudist software to code and categorise the email content as recommended by Zamawe (2015) before generating Word Clouds based on the frequency of emerging themes. Word Clouds are useful visual depictions of text data (Cappelli et al., 2017) and such pictorial representation of data was deemed appropriate to organise and summarise the research data in this study.

Six pre-determined questions were posed to three expert wellness tourism participants to uncover their perceptions of wellness tourism, assessment of the challenges facing the sector, and to ascertain the extent to which, if any, the upward growth in wellness tourism will be realised post COVID-19. As such, the results of this study reflect the perceptions of three prominent tourism wellness representatives in three different destinations during the COVID-19 outbreak. While the small sample size will evidently restrain the generalisability of the results, the deeply reflective answers arising from across three geographically diverse samples have resulted in findings that may have application outside of these research settings. The results offer insights and understanding with wider relevance to wellness tourism to stimulate further research that will assist researchers, policy makers and industry stakeholders to move forward as destinations embrace the wellness boom.

In articulating the meaning of wellness tourism, expert (A) considered:

‘Wellness Tourism is travel that seeks physical, mental, and spiritual well-being, associated with the infrastructure that tourism offers, such as transportation and lodging. Although there is a wide dissemination of tourism and health, the population still has little understanding of the relationship and interdependence between the two areas. There is a certain rejection by the medical segment of the term tourism or other health-related terms, thus failing to recognize the importance and relationship of the two areas that would be a major stimulus to the development of health and wellness tourism in the world. If health and medical authorities publicly recognized that travel related to wellness in all segments brings benefits to society and were more encouraged, we would have a greater acceptance by the whole society.’ (Expert A).

Expert B contended that wellness tourism ‘is a trip to create, to maintain well-being, whether mental, physical, or social’ (Expert B), while Expert (C) defined Wellness Tourism as ‘a kind of tourism focused on maintaining or improving the well-being of the tourist who enjoys it’ (Expert C).

In assessing the value and importance of wellness tourism to the economy, Expert A noted that:

‘The Tourism and Health Industries move trillions in the world economy separately, and together they end up generating much more income, and jobs, in virtually every country around the globe. These are two segments that are always investing in innovations, equipment, structure improvements, hiring and qualification of new professionals, among others, which make it possible for many places to be positively affected by Wellness Tourism.’ (Expert A).

In the context of the industry post COVID-19, Expert A claimed that:

‘Thinking about the activity in the post-pandemic future will only grow this activity and always increase the economy. Due to the Covid-19 pandemic travel has been restricted, but this has not diminished people’s desire and needs to travel. Now there are many more people who want to take better care of themselves and their health. This concern with well-being often includes places other than one’s own home, such as clinics, hotels, and spas. And many of these establishments are preparing for the increase in this damned and potential demand for the coming years. An important detail that was mentioned is that only the places that suffered travel restrictions had a significant drop in the volume of visitors to Wellness-related establishments. Where they were allowed to operate, the impact was minimal, showing that the activity, which was already growing, only tends to increase after this pandemic period. It will be a time when people will take much more care of themselves, whether physical or mental, and these places will be increasingly sought out to meet these needs.’ (Expert A).

In continuing this discussion, Expert A noted that:

‘Concerning the challenges that Wellness Tourism will face after the Covid19 Pandemic, it is believed that convincing public authorities of the high importance of people’s physical, mental, and psychological well-being will be the most difficult. This type of service needs to be considered essential since during the pandemic most places were closed. It has been found that due to the restrictions imposed by the Covid19 Pandemics many people’s health has worsened, such as high rates of suicide, depression, and anxiety, so depriving people of using Wellness services is making them sick early. We believe that strengthening safety protocols is paramount, since institutions that work with Wellness already have strict protocols to avoid infection and contamination, and a broad campaign publicizing the benefits that outweigh the risks will be of great importance to stimulate Wellness in the coming years.’ (Expert A).

Expert B noted that:

‘According to the research done this segment tends to grow a lot, after the coronavirus restrictions pass. The focus on taking care of wellness had a very big increase during the pandemic, and it will be very important for people to stay healthy afterward. It is important to stress that the demand needs to remain strong and willing to consume, one of the challenges of the sector, because many borders are still closed and it is necessary to train the employees well, who offer wellness activities. The connection with nature is a major focus of the activity, along with healthy food, good accommodations, and staff trained to provide the best service.’ (Expert B).

For Expert C:

‘Tourism tends to increase due to the pandemic because people are looking for better health, to improve their physical and mental well-being, and these are points that Wellness can solve, besides being the key factor to happen, the confidence that the tourist’s health is being taken care of.’ (Expert C),

and noted that:

‘The great challenge for growth and continuity to be maintained is that people still do not feel as confident to travel, due to the restrictions imposed by the pandemic. How to get to the destination is what worries the agents of this segment’ and reflects that wellness tourism is (Expert C);

‘A type of tourism that brings foreign exchange with shopping that is a unique experience for the users’ (Expert C).

In evaluating the potential growth of wellness tourism, Expert (A) suggested that:

‘Regarding the main trends of the segment for the future, it should be noted that there will be a large increase in demand for health and wellness services in the coming years. People are becoming aware of how necessary physical and mental well-being is. Studies have shown that Covid-19 was more deadly in those who were obese, sedentary, and had comorbidities or health problems, and much of it was preventable like hypertension, diabetes, etc. In other words, it has only increased the awareness of how important and necessary good health linked to wellness is in facing new diseases. There will be more options for activities within Wellness Tourism in the coming years, even thinking about adaptation to new diseases. One increase already seen is that of remote assistance, something that was not so common in Wellness, since physical contact needs to be made with great caution, an alternative to this has already begun to be created.’ (Expert A).

Expert (B) identified the tourism industry as:

‘one of the great pillars of the economy, bringing many jobs, foreign exchange, and helping other sectors as well. Tourism helps in the growth and development of local communities when inserted into the activity. Some trends pointed out are travel with transformative experiences, regenerative travel, the return to ancient traditions and rituals, the inclusion of pets in therapies, physical experiences in nature, such as cycling, hiking, camping, and places that rely on biophilic design, always integrating nature in the activities.’(Expert B),

while Expert (C) proposed that:

‘The main trends for the future are believed to be the search for treatments for the sequelae of Covid-19, the search for Mind Detox, the search for weight loss, treatments for anxiety and depression, and socialization in healthy environments.’ (Expert C).

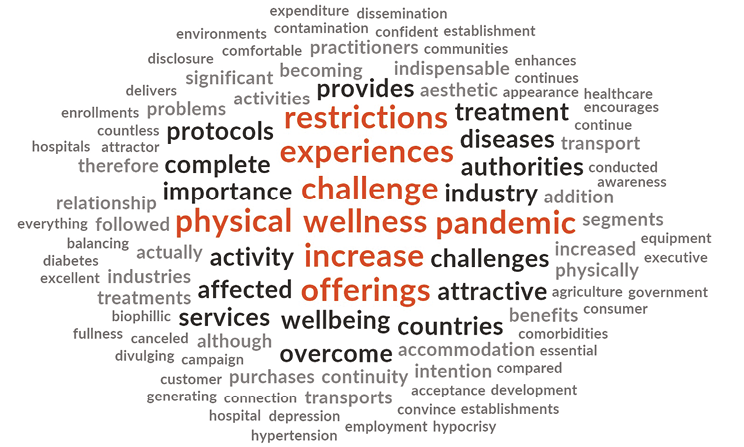

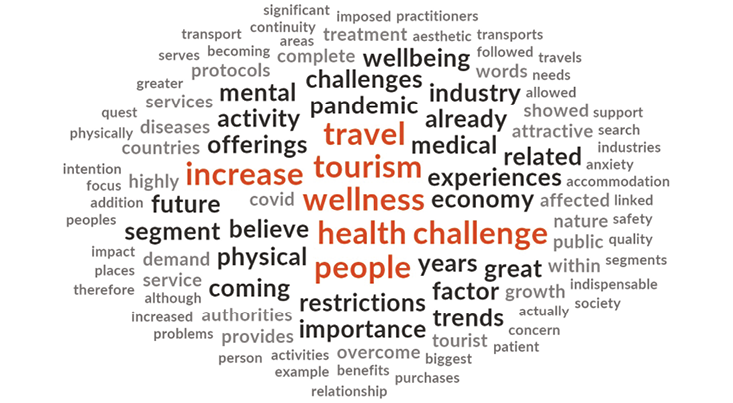

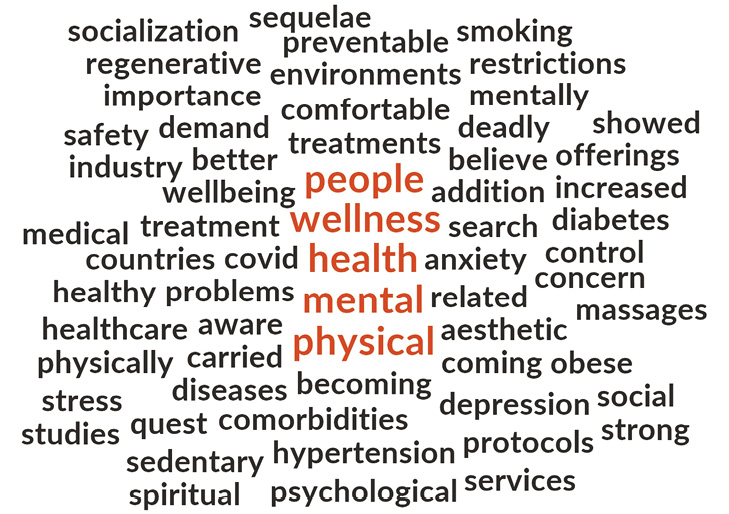

Following the data collection phase, a detailed content analysis was undertaken generating three Word Clouds to visually present and determine shared perspectives and consensus arising from the data set. Keywords most frequently mentioned by respondents were captured in larger orange text with those mentioned less often were presented in smaller black text. Figure 2 depicts the most frequently cited words comprising a minimum of eight letters and Figure3 illustrates words most frequently mentioned that contain at least five letters. Given that health was one of the most dominant words cited across all interviews, Figure 4 presents a word cloud that concentrates on health-related terms which was designed after interviewees’ responses were categorised. Given the proliferation of a number of key terms such as restrictions, experiences, challenges, physical, wellness, pandemic, increase, offerings, travel, tourism, increase, people, health, and challenge a shared perspective between the interviewees is apparent.

Fig. 2. Word Cloud Content Analysis comprising words with at least 8 letters

Source: own work based on data provided by the three structured email interviews.

Fig. 3. Word Cloud Content Analysis comprising words with at least 5 letters

Source: own work based on data provided by the three structured email interviews.

Fig. 4. Word Cloud Content Analysis categorized by health-related and comprising words with at least 5 letters

Source: own work based on data provided by the three structured email interviews.

The research findings in this study reinforce and corroborate the work of other researchers and strives to further inform academics, governments, developers, and other decision-makers in the tourism wellness industry. As observed by Abbas et al. (2021), the wellness tourism segment will increase exponentially. The outbreak of COVID-19 has not dampened growth – rather the pandemic has accelerated the growth of tourism wellness primarily due to a heightened awareness of health and most notably mental health concerns. On the one hand, rapidly expanding demand requires new strategies to personalise and differentiate products and services while on the other hand alleviating the simultaneous increase in tourists risk perceptions and risk averse tendencies to mitigate the spread of the virus need attention (Rahman et al., 2021) .

A recent study by Han and An (2022) assessed the perception of wellness tourism before and after the COVID-19 pandemic in Korea by extracting and analysing keywords related to wellness tourism from online social networks. Their results indicated that the desire for healing of both body and mind appeared more significant after the outbreak and concluded that government action was needed to revitalise and boost local wellness tourism (Han and An, 2022). In a related study, Sivanandamoorthy (2021) evaluated the impact of the pandemic on the wellness tourism of Sri Lanka, a traditional destination for western European travellers using semi-structured interviews. The study determined that wellness tourism in Sri Lanka has been severely disrupted, faced significant challenges and advocated that authorities and hotel brands explored the potential of local nature resources and focused on ethical strategies and regulations to assist in mitigating the effects of the pandemic.

Fontoura, Lusby and Romagosa (2020) adopted qualitative research methodologies including personal communication, secondary data analysis and one-on-one interviews with experts to analyse the tourism industry post-COVID-19 in Brazil and USA. In the case of Brazil, the lack of consistent action from the central government demonstrated through examples of inadequate local public administration and the need for private initiatives such as the provision of sanitary measures and funding to address the tourism crisis. In the context of the USA, Fontoura et al. (2020) have suggested the COVID-19 crisis is more negatively impactful than the Great Depression and the September 11th attacks, and estimate that the travel industry would report losses of USD 519 billion this year (US Travel Association, 2020). According to the US Travel Association, geographical differences were observed with 75% of residents in the Northeast planning to halt all travel, compared to only 59% of residents in the South and 57% of residents in the Midwest. The majority of Americans agreed that the compulsory use face masks was a positive measure noting that American tourists preferred destinations that imposed a mask mandate and offered local and outdoors activities which suggested that natural attractions, national parks and smaller communities would become more popular among US tourists (US Travel Association, 2020). Finally, Fontoura et al. (2020) noted the importance of introducing sustainable initiatives was necessary to harness wellness tourism in these destinations. This is consistent with Dionísio and Rodrigue’s (2021) study which investigated the tourism industry crisis in Portugal during the pandemic outbreak and concluded that sustainable strategies were central to the revival of the Portuguese tourism industry advising that the creation of initiatives such as the ‘Clean and Safe’ stamp were necessary for the visitor experience in the new ‘normal’.

In line with the results of previous studies, this current research study recognises that changing consumer attitudes and demands for health and wellness requires destinations to embrace this phenomenon by investing in sustainable wellness tourism. “Welltodo” website (2020) has declared that operators are becoming more competitive with new offerings disturbing traditional wellness tourism players from wellness tourism to spa tourism, workplace wellness, personal care, traditional health, complementary therapies, mindfulness, and fitness. With many borders reopened, it is now time to follow a multi-step approach for wellness tourism to overcome the COVID-19 crisis. It is also time for governments and authorities to create new regulations and safety guidelines, for tourism policy-makers and practitioners to design new wellness luxury and safety strategies, and for destinations to provide the enhanced and authentic experiences demanded by wellness consumers post-COVID-19.

This study identified the upward trend in wellness tourism and assessed the many significant challenges the industry is facing from the perspective of prominent wellness tourism experts. Notably two of these experts represent destinations featured in the top twenty wellness tourism places in the world, are among the countries most affected by COVID-19 with few wellness tourism research studies specifically focusing on these specific destinations. Notwithstanding its contribution, this study has several limitations. Firstly, the small sample size restricts the generalisability of the findings and future research could capitalise on this research by employing a more extensive sample to allow for greater depth of understanding across multiple wellness tourism destinations. Secondly, perceptions of wellness tourists post COVID-19 have not been explored and it is proposed that capturing such perceptions represent an important research agenda to inform sustainable wellness tourism strategies. Thirdly, some researchers argue that written responses of email interview lack the social cues that assist the full understanding of the respondent’s experience as it is not possible to observe or interpret visual cues, tone, silence, or hesitation (Fritz and Vandermause, 2017). However, the researchers in this study contend that even with additional written cues, researchers cannot respond in real-time or capture emotions. Finally, the consideration of participant characteristics is essential for determining that email interviews are appropriate in terms of internet connectivity, cyber security breachers, and discomfort with email communication. All participants in this study were wellness tourism experts, had computer access, have consistent internet connectivity, routinely communicated via email, and no data breach concerns were noticeable.

The results and trends observed in this study from the perspective of wellness tourism experts anticipate ongoing and exponential growth of wellness tourism after the COVID-19 pandemic. The value and importance of wellness tourism destinations that support physical and physiological outdoor, fitness, and spiritual activities is central to recovery which can only be achieved through sustainable, personalised, authentic, and distinctive wellness tourism offerings.

This study aims to advance wellness tourism academic research and to inspire new and creative future research stands in this important field of study. The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the tourism industry are unquestionable and wellness tourism is well placed to drive the industry’s recovery. This will require planning and strategies informed by multiple stakeholders so that destinations can sustainably embrace this declared wellness boom.

Acknowledgements. This work was funded by national funds through FCT – Foundation for Science and Technology I.P., within the scope of reference project no. UIDB/04470/2020.

ABBAS, J., MUBEEN, R., IOREMBER, P. T., RAZA, S. and MAMIRKULOVA, G. (2021), Exploring the impact of COVID-19 on tourism: transformational potential and implications for a sustainable recovery of the travel and leisure industry, Current Research in Behavioral Sciences, 20, 100033. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crbeha.2021.100033

ADAMS, T. B. (2003), ‘The Power of Perceptions: Measuring Wellness in a Globally Acceptable, Philosophically Consistent Way’, Wellness Management, http://www.hedir.org/

AHORSU, D. K., LIN, C. Y., IMANI, V., SAFFARI, M., GRIFFITHS, M. D. and PAKPOUR, A. H. (2020), ‘The fear of COVID-19 scale: development and initial validation’, International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 20, pp. 1537–1545. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-020-00270-8

ANSER, M. K., SHARIF, M., KHAN, M. A., NASSANI, A. A., ZAMAN, K., ABRO, M. M. Q. and KABBANI, A. (2021), ‘Demographic, psychological, and environmental factors affecting student’s health during the COVID-19 pandemic: on the rocks’, Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 28 (24), pp. 31596–31606. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-021-12991-x

BARDIN, L. (1977), Análise de conteúdo, Lisboa: Edições 70.

BELL, S. L., PHOENIX, C., LOVELL, R. and WHEELER, B. W. (2015), ‘Seeking everyday wellbeing: The coast as a therapeutic landscape’, Social Science & Medicine, 142, pp. 56–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.08.011

CAPPELLI, L., D’ASCENZO, F., NATALE, L., ROSSETTI, F., RUGGIERI, R. and VISTOCCO, D. (2017), ‘Are Consumers Willing to Pay More for a “Made in” Product? An Empirical Investigation on “Made in Italy”, Sustainability, 9 (4), 556. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9040556

CHEN, J. S. (2007), ‘Wellness tourism: Measuring consumers’ quality of life’, Proceedings of the First Hospitality and Leisure: Business Advances and Applied Research Conference, July 5–6, 2007, Lausanne, Switzerland, pp. 38–49.

CHHABRA, A., MUNJAL, M., MISHRA, P. C., SINGH, K., DAS, D. and KUHAR, N. (2021), ‘Medical tourism in the COVID-19 era: opportunities, challenges and the way ahead’, Worldwide Hospitality and Tourism Themes, 13 (5), pp. 660–665. https://doi.org/10.1108/WHATT-05-2021-0078

DEESILATHAM, S. (2016), Wellness Tourism: Determinants of Incremental Enhancement in Tourists’ Quality of Life (Doctoral dissertation), School of Management Royal Holloway, University of London

DILLETTE, A. K., DOUGLAS, A. C. and ANDRZEJEWSKI, C. (2020), ‘Dimensions of holistic wellness as a result of international wellness tourism experiences’, Current Issues in Tourism, 24 (6), pp. 794–810. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2020.1746247

DIONÍSIO, I. and RODRIGUES, A. I. (2021), ‘A adoção do selo «Clean & Safe» em tempos de COVID-19: Oportunidades e desafios para a inovação e reinvenção no sector da animação turística em Portugal?’, A Multidisciplinary e-Journal, 40, pp. 79–98. https://doi.org/10.18089/DAMeJ.2021.40.5

DUAN, L., SHAO, X., WANG, Y., HUANG, Y., MIAO, J., YANG, X. and ZHU, G. (2020), ‘An investigation of mental health status of children and adolescents in china during the outbreak of COVID-19’, Journal of Affective Disorders, 275, pp. 112–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.06.029

DUNN, H. L. (1959), ‘High-level wellness for man and society’, American Journal of Public Health, 49 (6), pp. 786–792. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.49.6.786

ELLIS, J. C. (2013), The impact of postsecondary fitness and wellness courses on physical activity behaviors (Doctoral dissertation), Walden University.

FRANCO, M. L. P. B. (2008), Análise de conteúdo, 3rd ed. Brasília: LíberLivro.

FONTOURA, L., LUSBY, C. and ROMAGOSA, F. (2020), ‘Post-COVID-19 tourism: perspectives for sustainable tourism in Brazil, USA and Spain’, Revista Acadêmica Observatório de Inovação do Turismo, pp. 16–28. https://doi.org/10.17648/raoit.v14n4.6654

FRITZ, R. L. and VANDERMAUSE, R. (2018), Data Collection via In-Depth Email Interviewing: Lessons From the Field, Qualitative Health Research, 28 (10), pp. 1640–1649, Epub 2017 Jan 17. PMID: 29298576. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732316689067

GLOBAL WELLNESS INSTITUTE (2018),Global Wellness Tourism Economy, https://globalwellnessinstitute.org/wpcontent/uploads/2019/04/GWIWellnessEconomyMonitor2018_042019.pdf

GLOBAL WELLNESS INSTITUTE (2021), The Global Wellness Economy: Looking Beyond COVID, https://globalwellnessinstitute.org/industry-research/the-global-wellness-economy-looking-beyond-COVID/

GUDIÑO, D., FERNÁNDEZ-SÁNCHEZ, M. J., BECERRA-TRAVER, M. T. and SÁNCHEZ, S. (2022), ‘Social Media and the Pandemic: Consumption Habits of the Spanish Population before and during the COVID-19 Lockdown’, Sustainability, 14 (9), 5490.https://doi.org/10.3390/su14095490

HAN, J. H. and AN, K. S. (2022), ‘Comparison of Perceptions of Wellness Tourism in Korea Before and After COVID-19: Results of Social Big Data Analysis’, Global Business & Finance Review, 27 (2), pp. 1–13. https://doi.org/10.17549/gbfr.2022.27.2.1

JONES, I. and GRATTON, C. (2010), Research Methods for Sports Studies: Third Edition (2nd ed.), Routledge.https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203879382

KELLERT, S. R., HEERWAGEN, J. and MADOR, M. (2008), ‘Dimensions, Elements, and Attributes of Biophilic Design’, [in:] Biophilic Design: The Theory, Science, and Practice of Bringing Buildings to Life, Hoboken, NJ, USA: Wiley.

KONCUL, N. (2012), ‘Wellness: A New Mode of tourism’, Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja, 25 (2), pp. 525-534. https://doi.org/10.1080/1331677X.2012.11517521

LAING, J. and WEILER, B. (2008), ‘Chapter 31 - Mind, Body and Spirit: Health and Wellness Tourism in Asia’, [in:] In Advances in Tourism Research, Asian Tourism, Elsevier, pp. 379–389. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-045356-9.50037-0

LAW, M. (2022), How travel companies are using the wellness boom to reinvigorate the industry, https://www.smartcompany.com.au/industries/tourism/travel-companies-wellness-boom/ [accessed on: March 2022].

LEW, A. A., CHEER, J. M., HAYWOOD, M., BROUDER, P. and SALAZAR, N. B. (2020), Visions of travel and tourism after the global COVID-19 transformation of 2020, Tourism Geographies, 22 (3), pp. 455–466. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2020.1770326

LOUNSBURY, J. W. and HOOPES, L. L. (1986), ‘A vacation from work: Changes in work and nonwork outcomes’, Journal of Applied Psychology, 71 (3), pp. 392–401. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.71.3.392

MAJEED, S. and RAMKISSOON, H. (2020), ‘Health, Wellness, and Place Attachment During and Post Health Pandemics’, Frontiers in Psychology, 11, art. no. 573220. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.573220

MEDINA-MUÑOZ, D. R. and MEDINA-MUÑOZ, R. D. (2013), ‘Critical issues in health and wellness tourism: An exploratory study of visitors to wellness centres on Gran Canaria’,Current Issues in Tourism, 16 (5), pp. 415–435. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2012.748719

MEHO, L. I. (2006), ‘E-mail interviewing in qualitative research: A methodological discussion’, Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 57 (10), pp. 1284–1295. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.20416

MOHAN, D. and LAMBA, S. M. (2021), Wellness Tourism Will Flourish in the Post COVID era, https://www.hospitalitynet.org/opinion/4102574.html [accessed on: 20.02.2021].

MUELLER, H. and KAUFMANN, E. L. (2000), ‘Wellness tourism: Market analysis of a special health tourism segment and implications for the hotel industry’, Journal of Vacation Marketing, 7 (1), pp. 5–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/135676670100700101

MUSTAFA, A., ALAM, M. S. and SHEKHAR, C. (2020), ‘The Effects of Social Media Consumption Among the Internet Users During COVID-19 Lockdown in India: Results from an Online Survey’, Online J Health Allied Scs., 19 (4), p. 6, https://www.ojhas.org/issue76/2020-4-6.html

MYERS, J. E., SWEENEY, T. J. and WITMER, M. (2000), ‘The Wheel of Wellness Counseling for Wellness: A holistic model for treatment planning’, Journal of Counseling and Development, 78 (3), pp. 251–266. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6676.2000.tb01906.x

NAHRSTEDT, W. (2008), ‘From medical wellness to cultural wellness: New challenges for leisure studies and tourism policies, Keynote Speech’, The Future of Historic Spa Towns Symposium.

NAVARRETE, A. P. and SHAW, G. (2021), ‘Spa tourism opportunities as strategic sector in aiding recovery from COVID-19: The Spanish Model’, Tourism and Hospitality Research, 21 (2), pp. 245–250. https://doi.org/10.1177/1467358420970626

NEAL, J. D., UYSAL, M. and SIRGY, M. J. (2007), ‘The effect of tourism services on travelers’ quality of life’, Journal of Travel Research, 46 (2), pp. 154–163. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287507303977

ŐRI, D., MOLNÁR, T. and SZOCSICS, P. (2021), ‘Mental health-related stigma among psychiatrists in light of COVID-19, Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 58, 102620. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2021.102620

ORÎNDARU, A., POPESCU, M. F., ALEXOAEI, A. P., CAESCU, S. C., FLORESCU, M. S. and ORZAN, A. O. (2021), ‘Tourism in a Post-COVID-19 Era: Sustainable Strategies for Industry’s Recovery’, Sustainability, 13 (12), 6781, pp. 1–22. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13126781

PUCZKÓ, L. and BACHVAROV, M. (2006), ‘Spa, bath, thermae: What’s behind the labels?’, Journal of Tourism Recreation Research, 31 (1), pp. 83–91. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2006.11081250

RAHMAN, M. K., GAZI, M. A. I., BHUIYAN, M. A. and RAHAMAN, M. A. (2021), ‘Effect of COVID-19 pandemic on tourist travel risk and management perceptions’, PLOS ONE, 16 (9), e0256486. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0256486

RATISLAVOVÁ, K. and RATISLAV, J. (2014), ‘Asynchronous email interview as a qualitative research method in the humanities’,Human Affairs, 24, pp. 452–460. https://doi.org/10.2478/s13374-014-0240-y

REARDON, S. (2015), ‘Ebola’s mental-health wounds linger in Africa’, Nature, 519, pp. 13–14. https://doi.org/10.1038/519013a

ROKNI, L. (2021), ‘The Psychological Consequences of COVID-19 Pandemic in Tourism Sector: A Systematic Review’, Iranian Journal of Public Health, 50 (9), pp. 1743–1756. https://doi.org/10.18502/ijph.v50i9.7045

ROMAGOSA, F. (2020), ‘The COVID-19 crisis: Opportunities for sustainable and proximity tourism’, Tourism Geographies, 22 (3), pp. 690–694. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2020.1763447

RYAN, C. (1997), The Tourist Experience: A New Introduction, London: Cassell.

SAHOO, S., MEHRA, A., SURI, V., MALHOTRA, P., YADDANAPUDI, L. N., PURI, G. D. and GROVER, S. (2020), ‘Lived experiences of the corona survivors (patients admitted in COVID wards): a narrative real-life documented summaries of internalized guilt, shame, stigma, anger’, Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 53, 102187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102187

SEATON, A. V. and BENNETT, M. M. (1996), The Marketing of Tourism Products: Concepts, Issues, and Cases, London: International Thomson Business Press.

SHIGEMURA, J., URSANO, R. J., MORGANSTEIN, J. C., KUROSAWA, M. and BENEDEK, D. (2020), ‘Public responses to the novel 2019 coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in Japan: mental health consequences and target populations’, Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 74 (4), pp. 281–282. https://doi.org/10.1111/pcn.12988

SIBI, P. S., ARUN, D. P. and MOHAMMED, A. (2020), ‘Changing Paradigms of Travel Motivations Post COVID-19’, International Journal of Management, 11 (11), pp. 489–500. doi:10.34218/IJM.11.11.2020.047

SIVANANDAMOORTHY, S. (2021), ‘Exploring the impact of COVID-19 on the wellness tourism in Sri Lanka’, International Journal of Spa and Wellness. https://doi.org/10.1080/24721735.2021.1987001

SMITH, M. and PUCZKÓ, L. (2009), Health and Wellness Tourism, London: Butterworth-Heinemann, United Kingdom.

SMITH, M. and PUCZKÓ, L. (2014),Health, Tourism and Hospitality: Spas, Wellness and Medical Travel (2nd ed.), Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203083772

SPAFINDER WELLNESS 365TM. (2015), 2015 State of wellness travel report, http://veilletourisme.s3.amazonaws.com/2015/09/SFW_WellnessTravelReport091415FINAL.pdf

US TRAVEL ASSOCIATION. COVID-19 Travel Industry Research, https://www.ustravel.org/toolkit/COVID-19-travel-industry-research

VOIGT, C., BROWN, G. and HOWAT, G. (2011), ‘Wellness tourists: In search of transformation’, Tourism Review, 66 (1/2), pp. 16–30. https://doi.org/10.1108/16605371111127206

VOIGT, C. and PFORR, C. (Eds.). (2013), Wellness Tourism: A Destination Perspective (1st ed.), Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203079362

WANG, G., ZHANG, Y., ZHAO, J., ZHANG, J. and JIANG, F. (2020), ‘Mitigate the effects of home confinement on children during the COVID-19 outbreak’, Lancet, 395, 10228, pp. 945–947. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30547-X

WILSON, E. O. (1984), Biophilia, Cambridge, MS, USA: Harvard University Press. https://doi.org/10.4159/9780674045231

WELLTODO website by Fitt Insider. How Leading Wellness Brands Are Navigating Employee Wellbeing In A New Reality, https://www.welltodoglobal.com/how-leading-wellness-brands-are-navigating-employee-wellbeing-in-a-new-reality/

ZAMAWE, F. C. (2015), ‘The implications of Using NVivo Software in Qualitative Data Analysis: Evidence-based Reflections’, Malawi Medical Journal, 27 (1), pp. 13–15. https://doi.org/10.4314/mmj.v27i1.4