Introduction. Theoretical and contextual framework

The conquest of the Gallaeci and the consolidation of Roman rule in the Northwest of Hispania took place around the turn of the millennium. It is a time of expansion and economic growth for Rome, which allowed the extension of social mobility and the imperial elite, but it also meant an important political change that consisted of the transition from a republican system to an autocratic system in the figure of Augustus and successive emperors. Wallace-Hadrill (1989) called this series of changes the “Roman cultural revolution” when he reviewed Zankerʼs book, The Power of Images, in 1989. The key to this revolution is that it affected not only Rome, but also provincial cultures, which they conformed at the same time as Roman identity and its history. It is not possible to talk about a “pure” Roman culture (Wells 1999: 189). In that sense, it is possible to affirm that a dialectical process of identity negotiation was taking place in the turn of the millennium. We do not intend to further stir up the heated debate on Romanization, but we must indicate that our interpretation moves in the field of postcolonial theory, that is, away from the traditional views on Romanization criticized by Hingley (1996, 2008, 2011).

As Greg Woolf (1998: 193–194) expresses for the case of the Gallic communities, the Iron Age cultures were quickly altered and integrated into a “system of structured differences” throughout the Empire, but the same system also was modified gradually at the beginning of the Imperial period. In the case of the Northwest of Hispania, the arrival of Rome meant a revolutionary and lasting structural transformation, although the central power did not want to conduct these changes intentionally. Rome itself never tried to convert those populations into something different in a conscious way. The Roman Empire never ever had this power; on the contrary, it limited itself to sanctioning them (Veyne 1991: 418). What changed were the material cultures of the conquered communities, what has been called traditionally a ”Romanization”. Nevertheless, the study of whether or not the autochthons were Romanized is sterile, since the so-called “Roman provincial cultures” did not exist before the conquest, so they were not able to be imposed or adopted by any people (Woolf 1997: 347).

In this article we prefer to speak of a long-term process of cultural hybridization in which the identities of these inhabitants have been reconfigured by the introduction of new material and symbolic elements. Roman power was a decisive factor in the cultural change, but not the only one. One of the keys to understanding what these transformations consisted of and what their consequences were for society is to analyze everyday life in relation to consumption patterns. What was consumed and how it was consumed was (and is) a way of expressing an identity. This is evidenced by the intense debate that has taken place since the Republic and also during the Imperial period about the way members of the elite dressed and dined, but also about their homes and the public buildings they promoted. We are talking about the Sumptuariae Leges which were promulgated during the Roman times (Crespo Pérez 2018). A common feature of these laws is the rejection of luxury, but at each historical moment what is considered luxuria is different. There are no traces in the sources of sanctioning procedures as well as of the imposition of censorship notes; this situation was explained by Venturini (2016), who hold that these laws found a custom which discouraged the application of punitive actions.

We therefore apply Foucault’s theory to the study of the archaeological record, so that we can learn about forms of domination over the conquered. That is, what kind of repressive strategies the Romans used informally against the Galicians. It is about analyzing those spaces and objects where power is manifested and the ways in which it is exercised, always in an ascending way (Foucault 1978: 144). This implies shifting the focus of attention from the legal apparatus of the State to the local networks of subjection and their tangible forms (Foucault 1978: 147). Power permeates any reality, including the subjugation of the body, the guide of the gesture and the choice of behavior (Foucault 1978: 143). This is the main reason we do not study here specific laws created by Rome (since they do not correspond, furthermore, to the case of Gallaecia), but rather the artistic expression chosen by some elites for their funerary monuments in the field of their local power. It is in the sphere of everyday life that power strategies and relations of inequality can be found, which is related to the importance of social, cultural and symbolic capital that shapes these power relations (Bourdieu 1990: 112–122). The concept of habitus as a generating principle of other principles of social behavior (Bourdieu 1977: 78) is essential in this analysis, as the material culture is necessary for the conformation of the habitus. Its construction materializes, for example, in the ceramics that the Gallaeci used to cook and serve their food, in their way of dressing and how they chose to represent themselves in their tombs. It is the everyday environment where the bases of social behavior and the creation of habitus schemes that function beyond the conscious and discursive realm are best appreciated (Bourdieu 1977).

The stelae in the Northwest of Hispania

The spread of funerary stelae as a characteristically Roman monument was widely accepted in the Northwest of Hispania. According to Tranoy (1981: 347), the 79.6% of the funerary monuments in this area were stelae. This percentage is reduced to 61.4% in the specific case of the conventus of Lucus Augusti, which is the lowest compared to the conventus of Bracara Augusta (77.4%) and Asturica Augusta (84.5%) (Tranoy 1981: 347). They were a brand-new funerary monument that had never been seen before in this territory. The world of death in Gallaecia is transformed by the arrival of Rome. Until then, death had been absent in the daily life of these societies, but once conquered by Rome, the funerary world becomes a fundamental and visible part of these communities. The space that death occupies is also a field of negotiation of the identity of the individual and his position in society (González Ruibal 2006–2007: 620).

The stelae represent a great innovation since they imply the incorporation of writing in a territory where it had never existed. Their main function was to preserve the memory of the dead, and through writing you can learn new, specific data about them, such as name and age (González García: 397–398). Until that moment, death in Gallaecia took place in the river, understood as a space of transition, always in movement (García Quintela 1997). The river Lethes[2], the sacred river of the Gallaeci, is the river of oblivion. The arrival of Rome presupposes the monumentalization of an ancestral death and its placement in a permanent space. The stelae served to mark the space where a tomb was located. Their main characteristic is their verticality, a reduced thickness and their frontality, that is, they are made to be seen from just one side (Cebrián Fernández 2000: 100–101). The stelae become a new field of identity negotiation and a space in which to invest symbolic capital (using Bourdieuʼs terminology) individually and accumulate power. It is no longer a question of reinforcing the collective identity, but that of the individual and his family (González Ruibal 2006–2007: 620).

These elements allow the study of “Romanization” from the private sphere, far from the collective image that can be reflected in the urban planning of cities and the monuments of public spaces, such as the forum (Jiménez Díez 2008: 18). In this line, the individual identity of certain individuals who are part of the elite is studied from the two-faced stelae. Notwithstanding this identity only makes sense if it is inserted within a broader discourse such as the society in which such a particular stela was produced. The funerary document is a sign and, therefore, has an arbitrary nature (Saussure 1984: 104).

On this occasion we have chosen as the object of study the two-sided stelae which were located in the necropolis of villas near Lucus Augusti. Their main characteristic is that they are carved on both sides, that is, they lose the frontality that characterizes all Roman stelae. Therefore, the Gallaeci of Roman times decided to take a funerary monument of Roman origin and change it according to their own taste. On the other hand, these stelae have another peculiarity: they are anepigraphic. This implies that the image is put before the epigraphic condition. No written words are needed. However, some authors maintain that these stelae could have had an inscription or plaque in the place where they were exposed that has not been preserved to this day (Acuña Castroviejo, Casal García 2011: 15). We think that the finding of five two-sided stelae with no engraved text cannot be a coincidence, but rather it demonstrates a conscious choice of the people who had made these funerary monuments.[3] These people understood the stelae from their own perception of reality. The double-sided anepigraphic stelae is a solution unknown in the rest of the Roman Empire, where some scenes are known, but these are always marginal motifs of the stelae since the protagonist is always the epigraphic text. In the cases that we analyze in this article, the scenes have a complex narration with references to Roman mythology and other unknown ones.

We realize that, in analyzing these funerary stelae, we cannot make generalizations about the elites of Lucus Augusti, and certainly not about their society as a whole, because funerary monuments are individual documents (González Ruibal 2006–2007: 620). Despite this, it can be affirmed that some members of the elite readapted the Roman stelae, the Roman funerary monument par excellence, following their own tastes. In line with Bourdieuʼs ideas, the appropriation of the stelae as funerary monuments by some members of the elite is a way of accumulating symbolic capital, since knowledge and, especially, recognition are the keys of this new artistic capital arrived from Rome and readapted to the needs of these elites (Bourdieu, 1997: 152). “The culture of noble Romans provided an inspiration and a resource from which others might select items with which to fashion their own distinctive social personae” (Woolf 1998: 170). It is not a question of understanding these changes as a mere emulation of the Roman conquerors, because most of the social groups were not capable of competing with them; groups of different statuses and individuals judged themselves and pursued to reflect in their consumption what they had become. In this sense, the forms of expression of the Roman elite could serve as an inspiration, that is, as yet another resource than choice in the formation of oneʼs own identity.

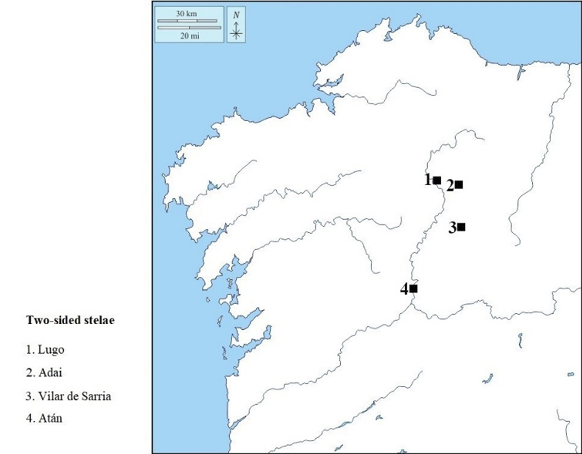

Given the stylistic correspondences between these two-sided stelae, it is said that a sculptorʼs workshop existed in Lucus Augusti (Acuña Castroviejo, Casal García 2011: 15), which we believe would have had a wide range of action of around seventy kilometers in straight line to the south. Alcorta Irastorza and Rodríguez Colmenero (2001: 229) proposed a radius of thirty kilometers, which we believe should be updated if the existence of a single officina for all the stelae is accepted, since the stela found in Atán is much further from Lugo than the rest and those others have only been found in the southern area of Lucus Augusti. Subsequently we think that this officina would be placed in Lucus Augusti or its surroundings, from where it would receive commissions in the southeast area of the Conventus Lucensis, specifically, in the territories of the eastern margin of the Miño River (see Figure 1). Nevertheless, we cannot conclude if it really was the same office over time or if there were at least two workshops that influenced each other. Precisely, the naturalism of the stela ubicated in Atán, the farthest of all the stelae from Lucus Augusti, stands out above the rest.[4] This makes us think that its officina could be a different one, but with a notable influence from the Lucus Augusti officina.

Fig. 1. Map of the two-sided stelae found in Gallaecia.

Romanitas: citizenship and togatus

The stelae presented in this article have in common that they contain representations of togatus, or figures in togas, which entails a whole series of implications. One of the fundamental elements that defines the Roman identity was the toga, considered by historiography as a legal status symbol of the person who wore it (Rothe 2020: 1–16). In Roman society, clothing became a way of expressing identity, as the values that each individual or group wanted to emphasize were highlighted through their clothing. By the late Republic, the toga evolved into a symbol of masculinity. But masculinity is constructed, is subject to negotiation, and often dependent on the elite men (Rothe 2020: 37–69).

In this sense, we must understand the toga representations, as their use is key to understanding how the communities conquered by Rome integrated informally into the Roman world. The choice of toga was not only a marker of legal status, the Roman citizenship, but served to create multiple sub-identities and, in essence, shape the Roman identity (Rothe 2020: 101–122). In ancient times, appearance played an active role in shaping identity and clothing was part of non-verbal language with strong moral connotations (Tellenbach 2014–2015: 38). In the same way, the toga became a differentiating element of gender and socio-economic status in Roman society. It is an expensive garment to maintain in good condition, so its use on a day-to-day basis involved a high economic level (Rothe 2020: 71–100; Tellenbach 2014–2015: 40). The Romans men chose to represent themselves in their funerary stelae with togas since the Republic, identifying toga with a Roman citizen, a legal status, a tradition that continued during the Imperial Age and was transferred to the provincial reality. Thus, the toga can be related to the capacity for political action of the individuals who wore it, that is, to the capacity to act in the politics of the Roman Empire, especially within the communities, whether they were coloniae or municipia (Rothe 2020: 123–146). The toga was worn by all those who participated in the institutions. It is true that Roman citizenship was transformed in the Imperial period, since it ended up being not only a set of rights and obligations, but also a form of social dignity that formed the Roman identity. Citizenship during the Imperial period was not expressed in the same sense as in the Republic, through voting and fighting in the legions; instead, the language of symbols showed what being Roman was meant to involve became more relevant.

It is important to keep in mind these characteristics of the toga in order to understand their relevance when we look at the double-sided stelae. In the absence of epigraphic text, the clothing of these figures provides us with information about who the patrons of these stelae were (Tellenbach 2014–2015: 46). The presence of these togatus (potential Roman citizens) can be explained by the proximity to an urban center (Rivas Fernández 1997: 101–102). All these stelae are exhibited in the Provincial Museum of Lugo (Galiza, Spain), in the room number 7, except for one of them that we will see below.

Stela of the ship

The first of these ones is the stela (IRG III 64; IRG 67) found in front of the Church of Villar de Sarria (Lugo) and today preserved in the Museum of Pontevedra. It is a granite block measuring 77 x 60 x 12 centimeters.

On the obverse there is a pair of standing human figures, one next to the other. They have been interpreted as the representation of a married couple who cross their right arm over their chest (Blázquez 2003: 6). They dressed according to the Roman style: on the right, the man wears a toga, a wide sinus, and bracelets; on the left, the woman wears stola and palla, and a veil or headdress (Díez Platas 2005: 63).

On the reverse there is a scene of navigation. There is a sailing boat whose prow ends in horse protome (Blázquez 2003: 6) or swan protome (Díez Platas 2005: 63), depending on the interpretation. Inside the ship, there are four figures from which only their heads protrude. The three of the right are looking at a fourth on the left, all of them in profile. This last figure is considered the main character for being the center of attention of the scene (Le Roux 1990: 141). At the bottom, below the ship, there is a swimming dolphin, and at the top there is an eagle with outstretched wings that holds a fish in its talons as if it were a lighting (Le Roux 1990: 142). One of the possible explanations for this scene is that it is the journey to the Beyond of the deceased in a Platonic and Pythagorean sense. According to Alonso Romero (1981, 2014: 95), the trip to the Beyond by ship may be related to the survival of a pre-Roman belief in which this ship is necessary to transport the deceased through a sea inhabited by sea monsters. On the other hand, Le Roux (1990: 142–143) suggests that the ship symbolizes the work that the deceased had performed during his life. Based on this statement, the eagle would refer to the good omens of Rome on the seas and would symbolize Jupiter, who would prevent storms. All this would justify that the deceased was in the service of Rome in its maritime undertakings. In addition, this scene was also considered to represent Ulysses and the sirens in the Odyssey, although this is a very doubtful interpretation because there does not seem to be a clear representation of the sirens (the dolphin?) or Ulysses (the main character?) (Blázquez 2003: 6–7). All researchers do not hesitate to indicate the funereal character of the eagle, so there seems to be no doubt that it is a funerary stela that would represent the deceased and a scene linked to the Beyond in some way, as has been attested in multiple stelae throughout the Roman Empire (Blázquez 2003: 7–8; Le Roux 1990: 143). Therefore, we do not think that this is a survival of a pre-Roman cult, but on the contrary a symbol of the integration of these dead into Roman society, as they may have chosen elements associated with Rome, such as the eagle and the ship journey in the funerary stela. In fact, the dolphin not only has a psychopomp character, but also began to be found on funerary stelae in the time of Augustus as a symbol of the triumph of Rome, as were the spurs of ships and swans (Zanker 1992: 106–108). This is also a reason we think that the protome of the ship represents a swan and not a horse, in the line of Díez Platas (2005: 63).

Despite the problems caused by its fracture, according to Blázquez (2003: 6), the stela could be dated between the end of the 1st century BC and early 1st century AD. To this end, the historian has conducted a comparative analysis of the toga folds from various reliefs from tomb stelae,[5] where he showed that they followed a fashion typical of the second half of the 1st century BC. Nevertheless, Alonso Romero (2014: 95) continued defending the dating of the stela around the 3rd century AD, as he had previously maintained (Alonso Romero 1981), although he did not provide any new arguments. Díez Platas (2005: 63) dates the stela to around the 2nd century in her article but does not provide any explanation. For this reason, added to the presence of spurs, dolphins, and eagles in the scene (Zanker 1992: 106–108), we consider Blázquezʼs dating to be closer to reality, so this stela is framed circa the 1st century AD.

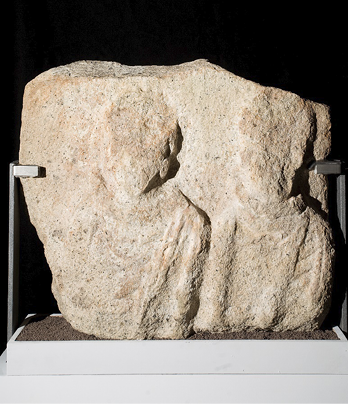

Stela of Hercules

The second stela (HEp 11, 2001, 312) was found in 1998 during the consolidation works of the Roman wall of Lugo in cubes 59 and 60, in the lower face. It is a granite block that measures 60 x 50 x 18 centimeters, which state of preservation is poor due to erosion. It is dated between the 2nd and 3rd centuries AD (Alcorta Irastorza 2011b; Alcorta Irastorza, Carnero Vázquez 2010: 171).

On the obverse (see Figure 2.1.) there are two characters in relief who are in a seated position. The heads, however, are not preserved, although the figuresʼ beaded necklaces can be seen, as well as the folds of the togas on the tunics (Alcorta Irastorza 2011b). This complicates making a correct identification of these two figures. In any case, it can be affirmed that both figures are in the same hierarchical plane, that is, there is equality between them. Therefore, it would be two individuals of the same status who wear togas, probably men belonging to the local elite. Some researchers considered that it could be a couple of man and woman (a marriage), or two women related to each other (Alcorta Irastorza, Carnero Vázquez 2010; Balseiro García, Carnero Vázquez 2011: 769). However, the fact that both are in the same position and, above all, that they wear togas, inclines us to think that they are men, Roman citizens. In addition, the right figure retains traces of paint, especially on the toga, where the white plaster and the red paint can be clearly seen. Thus, originally, this two-sided stela was painted (Alcorta Irastorza 2011b).

The reverse (see Figure 2.2.) shows a scene identified with the Labors of Hercules, characteristic of the Mediterranean area. There is a shape of a centaur, which could be Nesos, and a human figure to the right. This individual wears a kind of cap or what has been identified with a possible Nemean lion head. This would be Hercules, who carries a mallet which he is about to use on the centaur (Alcorta Irastorza 2011b; Alcorta Irastorza, Rodríguez Colmenero 1997: 228). In this case, a theme from classical mythology has been chosen to be sculpted on the back of the stela. This should not surprise us since the scenes of the labors of Hercules were spread throughout the Mediterranean in an exceedingly long space of time. It is noteworthy that only two characters are depicted, Hercules and Nesos, as it is usually the woman, the protagonist of the scene, who appears between the other two characters (Alcorta Irastorza, Rodríguez Colmenero 1997: 228).

Fig. 2.1. Stela of Hercules. Obverse.

Fig. 2.2. Stela of Hercules. Reverse.

Viewed in this way, this stela would have belonged to two men from the local elite of Lucus Augusti who were perfectly integrated into the Roman Empire, according to their clothing, characteristics of Roman citizens, and the scene of Hercules.

Stela of the Capitoline Wolf

The following stela (HEp 11, 2001, 311) was discovered next to the previous one, between cubes 59 and 60, in the same excavation campaign of 1998 in the wall of Lugo. Made in granite, its dimensions are 80 x 50 x 20 cm. It is more fractured than the stela of Hercules, as this one has lost some parts in the upper right and lower areas, resulting in a trapezoidal block. Even so its dating also moves between the 2nd and the 3rd centuries AD (Alcorta Irastorza 2011a; Alcorta Irastorza, Carnero Vázquez 2010: 171).

The obverse (see Figure 3.1.) features a seated togatus[6] that does not have the head, the right part of the body or its lower extremities. Only his left arm, which is parallel to his body, is well appreciated. It is observed how his right hand is holding the toga on the same side (Alcorta Irastorza 2011a; Alcorta Irastorza, Rodríguez Colmenero 1997: 223–226).

The front part of a wolf appears on the back of the stela (see Figure 3.2.). Beneath this she-wolf there are two figures (one of them cut out by the fracture of the stela) who are suckling from her. For this reason, this scene has been interpreted as a representation of the Capitoline wolf feeding Romulus and Remus (Alcorta Irastorza 2011a). In the lower right part, there is a silhouette interpreted as a tree, which could be a fig tree or the Lupercal forest. An extension is born from this tree that would be the fence that delimits the cave in which the scene takes place, according to mythological stories (Alcorta Irastorza, Rodríguez Colmenero 1997: 227–228).

Fig. 3.1. Stela of the Capitoline Wolf. Obverse.

Fig. 3.2. Stela of the Capitoline Wolf. Reverse.

According to Bianchi (1976), the Capitoline wolf was widely depicted on funerary stelae in northern Italy and Dacia. Probably its diffusion reached these areas due to the émigré soldiers. It would not be dismissed, therefore, that we are in the wake of a soldier. Nonetheless, as Alcorta Irastorza and Rodríguez Colmenero (1997: 228) rightly specified, the cult of the Capitoline wolf and Rome is attested in Lucus Augusti. As a consequence, it is possible to affirm that it is the stela of a figure who identifies himself with power, with Rome, both because of the clothing in which he chose to represent himself, and because of the scene of the Capitoline wolf on the reverse.

Stela of the equestrians

The fourth stela (HEp 7, 401) comes from Santo Estevo de Atán (Ferreira de Pantón, Lugo) and has the following dimensions: 80 x 72 x 35 centimeters. As in the previous stelae, the chosen material is also granite (Balseiro García, Carnero Vázquez 2011: 767).

On the obverse (see Figure 4.1.) there are two seated figures in high relief. There are several interpretations regarding the gender of these figures. At first, Rodríguez Colmenero (1997–1998: 86) considered that they were a man and a woman or even two women, mother and daughter. Years later, Blázquez (2003: 13) proposed that it is a married couple, but Díez Platas (2005: 64) suggested that these were two male figures. The reason for these differences can be found in the loss of the head and the complex analysis of clothing and body gestures. It is at this point that we must bear in mind the concept of Bourdieuʼs bodily hexis, which is “political mythology realized, em-boided, turned into a permanent disposition, a durable way of standing, speaking, walking, and thereby of feeling and thinking” (Bourdieu 1990: 70–71). The author himself is adamant that gender differences can be seen in postures, gestures, and body movements, which is a noteworthy point because it affects the Galician-Roman mentality that is reflected in the sculptural representation of human figures.[7]

Rodríguez Colmenero (1997–1998: 86) indicated that the figures wear tunics and togas held at chest height by an isiac knot. He drew attention to the fact that they appear to be holding rectangular pots or trays in their laps. Both persons have the same attitude, so probably they belong to the same gender. This could be the reason Rodríguez Colmenero specified that they could be a marriage, but also two women, since this author seems to have linked the offering attitude of the sculptures with the female gender. However, the archaeologist ventured that a third seated figure could be missing, since the stela is very mutilated in one of the areas. This third woman would form a triad of mother goddesses, characteristic of the British and Germanic world (Rodríguez Colmenero 1997–1998: 87). Therefore, we would no longer be facing a funerary stela, but rather a votive monument, dedicated to female divinities. The problem with this hypothesis, according to the author himself, is that this scene of mother goddesses is not related to the rear scene, associated with the male gender (Rodríguez Colmenero 1997–1998: 878–8). In second place, Blázquez (2003: 13) did not speak about the possibility of the third figure, but rather assumed that it was a marriage by analogy to other funerary stelae found in Hispania. Finally, Díez Platas (2005: 64) pointed out that the figures wore togas with the sinus marked and did not hesitate to classify them as male. Given the controversy, in the last publication on this stela, Carnero Vázquez (2011b: 26) chose to indicate that they were two figures in the same position, without mentioning their gender.

Fig. 4.1. Stela of the equestrian. Obverse.

To these interpretations must be added another proposal by Rodríguez Colmenero. The archaeologist declared that it was a complete stela of large dimensions, similar to the well-known stela of Crecente (HEp 13, 436), which is preserved in the Provincial Museum of Lugo. Thus, the stela of Atán would be only the intermediate register of the mentioned stela, losing the upper register with another scene and, in any case, the lower register with the epigraphic text (Rodríguez Colmenero 1997–1998: 86).

After a careful examination of Atánʼs stela in the Lugo Provincial Museum, we cannot confirm Rodríguez Colmeneroʼs hypothesis of the existence of a third figure. Although it is true that a part of the stela is very deteriorated, there is no reason to think that the scene on the reverse was larger and, therefore, there was another figure on the obverse. On the other hand, the clothing of the figures, as indicated by Díez Platas, is a toga in both cases. This fact, added to Rothe’s work and her reflection on the use of the toga in her latest book (Rothe 2020), lead us to think that, effectively, the seated figures are two men and not a married couple or two women.

On the reverse (see Fig. 4.2.) is a hunting scene divided by a horizontal line into two registers. In the upper one there are two riders, trotting on their mounts, which causes a slight distortion of the image. The horsemen’s heads and part of a horse are not preserved (Rodríguez-Colmenero 1997–1998: 86, 88). These equestrians are armed with oval shields, which, according to Blázquez (2003: 13), relates them to the Celtic peoples. The scenes of warriors on horseback are well known in Hispania as funerary motifs.[8] In fact, the analogy of the shields together with some details of the equestrians has made it possible to date the stela to the 1st century AD (Blázquez 2003: 13; Rodríguez 1997–1998: 86). The lower scene is a boar running after a hare. This whole scene of hunting is well documented in the Meseta.[9] Nevertheless, Blázquez (2003: 13) identified a pig represented on the stela of Atán and not a boar, as on the stelae of the Meseta, which he related to the sculptures of “verracos”. Notwithstanding, this interpretation is not clear, since the other authors do see a wild boar (Carnero Vázquez 2011b: 26; Díez Platas 2005: 64; Rodríguez Colmenero 1997–1998: 88). In our opinion, the silhouette corresponds to that of a wild boar, due to the position it adopts in pursuit of the hare, with raised ears and raised snout.

Fig. 4.2. Stela of the equestrian. Reverse.

Stela of circus games

The last stela was found in Vilamaior, Santa María Madalena de Adai, a town 5 km away from Lugo. It is a granite block measuring 92 x 57 x 13.5 cm fragmented in several places. The damage is related to the moment of discovery, as the stela appeared during construction work in 1977 (Arias Vilas 1991: 127; Carnero Vázquez 2011: 24).

On the obverse (see Figure 5.1.) there are two seated human figures. The faceless one who raises his hand to his chest has been identified with a man who, according to Díez Platas (2005: 65), wears a toga, as evidenced by the folds on his lower limbs. But Arias Vilas (1991: 127) affirms that it is a cloak because of the semicircle folds that cover his legs, an opinion shared by Carnero Vázquez (2011: 24). The researchers agree that this figure is a man who places his left hand on his chest. Nonetheless, the figure’s face is unrecognizable due to its deterioration. The other figure represents a woman without any doubt, since it has a tiara in a woman’s hairstyle, earrings, and bracelets on her wrists. Her arms rest on her lap. In this case, the female figure is clearly dressed in a long tunic that does not allow the ankles to be seen. Furthermore, the woman wears a cloak, which is held by a large elliptical brooch on her chest. It is worth noting the expressiveness of the womanʼs face, with large circular eyes and pupils (Arias Vilas 1991: 127; Carnero Vázquez, 2011: 24; Díez Platas 2005: 65).

Fig. 5.1. Stela of circus games. Obverse.

On the reverse (see figure 5.2.) there are two superimposed scenes, without a separation in registers. The upper zone shows a hunting scene or venatio, similar to that of the previous stela, as a man fights a bear with something like a trident. Although it is this weapon, the trident, that leads researchers to believe that this is a scene from circus games (Arias Vila 1991: 127). At the bottom there are three birds. The one on the left in a higher position than the rest resembles an owl, while the other two look at the first one and, despite having the same silhouette, they show assorted sizes (Balseiro García, Carnero Vázquez 2011: 767). This silhouette is clearly reminiscent of a blackbird, as Díez (2005: 65) affirms. The idea that they are pigeons (Arias Vila 1991: 127) must be banished.

Fig. 5.2. Stela of circus games. Reverse.

Due to the typology of the female hairstyle, the treatment of the face and the hieratic nature of the figure, the stela dates to the 4th century AD. In addition, according to Arias Vilas (1991: 127), it would be a transposition of the ivory diptychs from the end of the 4th century, which were only used by the privileged classes. We agree with this interpretation, although the parallelism with the Vilar de Sarria stela (Arias Vilas 1991: 127) seems uncertain, since there is a difference of around three hundred years between the two stelae.

Conclusions

The first four stelae described show that the Gallaeci adapted a Roman practice, such as the use of the funeral stela and the toga representations of the deceased, the imago, within their own social context. These Gallaeci in particular consciously decided to include reliefs on the obverse and reverse, unlike the common stelae, also using allegorical and mythological language to the reverse scenes. In addition, it is necessary to emphasize the gesture of these figures since many of them put their hands to their chests while holding the toga or stand erect to wear the toga properly. The very use of the toga entails entirely new gestures and modifications of bodily movements, associated with dignity, solemnity in the oratory of the institution and confinement, very different from those that could be performed in other garments, such as tunics, for those who had greater freedom of movement (Rothe 2020). The use of these scenes from Greco-Roman mythology and the toga were a symbol of status, of distinction. The stelae become objects of prestige in their own right, able to reach out to the entire population, including illiterate people who know the codes used on these stelae.

Although some authors (Alcorta Irastorza, Rodríguez Colmenero 2001: 226), have considered these stelae crude and lacking in expertise due to the schematism of the figures and the disproportion of the parts, we consider that Balilʼs words are still valid to understand Galician-Roman art:

Su frontalismo es intencional, no incapacidad para el escorzo, como intencionales son las posiciones de algunos miembros, no “ignorancia” para presentarlos de frente o de perfil, o el predominio de algunas partes del cuerpo frente a otras. Llámense escultores, artesanos o canteros, quienes labraron estas piezas sirvieron no a la idea, decimonónica, del “arte por el arte”, sino al gusto y exigencias, consecuencia de una formación cultural, de su clientela que prefería, como tantas veces sucede, lo habitual a lo insólito, aunque representara a una superación de los esquemas propios de la serie de talleres que, durante unos siglos labraron tales piezas (Balil 1978: 157).

Considering these significant examples of the two-sided stelae, we are able to conclude that the Gallaeci assumed Roman taste and values, which led to the creation of new variations. It is not a mere stylistic imitation, but the creation of a new cultural model (Woolf 1998: 203). On the other hand, in the 2nd and the 3rd centuries AD the Gallaeci, like the Gauls, were already legally integrated into the Roman Empire by virtue of Vespasianʼs (between 69 and 79 AD) granting of Latin law to all of Hispania, at which point the statute of foederata and free cities disappears, as well as that of many stipendiary cities, which became Latin municipalities. Later, this integration would be completed with the Constitutio Antoniniana promulgated by Caracalla in 212 AD, which granted Roman citizenship to the entire free population of the Empire (except for some recently settled foreigners and the peasants of Egypt) (Mangas 2015: 7). Therefore, in the 2nd and the 3rd centuries AD the Gallaeci were already integrated into the Roman orbit; they were Latin and, finally, Roman. They did not have to prove their romanitas to the ruling power (Woolf 1998: 203). Their status was no longer decided by the Roman administration; they were Roman at that point. Their material culture served, as it had already done in the Iron Age, as the means to achieve local goals. In other words, they played within a local level, which implied competing with neighbors of the same status and ensuring an internal hierarchy in the community. The key point is that these local traditions were now embedded in the dynamics of a province that was part of an imperialist cultural structure such as Rome (Woolf 1998: 205).

We disagree with traditional interpretations that assume a revival of indigenous culture after the Roman conquest, especially when speaking of ʻlethargyʼ (Acuña-Castroviejo 1974: 27–28), as if the Galician identity had no distinctiveness of its own until then. We must not understand these types of stelae as an expression of Roman culture, but rather as a reflect of a new local custom with specific characteristics. We are not talking about a manifestation of autochthonism here, since the morphology of the stelae and the choice of motifs prompt us to analyze this deeply symbolic formal repertoire within the Roman funerary field.[10] Acculturation cannot be understood as a process in which certain aspects of the native culture are replaced by others from the Roman culture (Wallace-Hadrill 2008: 10). It is not about looking for a dichotomy between native, Gallaeci in this case, and Roman, but rather that the two identities create a new hybrid culture. In this specific case, we have found the creation of two-sided stelae with their own idiosyncratic motives. This is how the term Romanization can be understood, which, in the words of Wallace-Hadrill (2008: 6), does not consist in being something, but in becoming something, that is, it is an extensive process in time linked with the repetition of certain actions, what Bourdieu calls habitus. Along these lines, we can speak of hybrid cultures, such as the Galician-Roman culture, where the Gallaeci and Romans interrelated and gave rise to a new provincial culture. This new culture was the consequence of the reciprocal exchange of elements, it was always in continuous dialogue and varied according to socio-economic status, gender, place, and age, but in no case did it eliminate past memories (Wallace-Hadrill, 2008: 7, 23). The cultures that developed in the Imperial era in each region were multiple and overlapped with previous ones; therefore, identities were dynamic and never monolithic, but existed on several levels simultaneously.

e-mail: natalia.gomez.garcia@ucm.es

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5060-3211

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5060-3211