Introduction

The 2nd century BC marks the beginning of the permanent Roman presence in the Iberian Peninsula; we know well the end of the process that resulted in the founding of the first Roman towns, but we are largely unaware of the previous trajectory of a period that has come to be known generically as “the first phase of the Roman conquest of Hispania”. It is on this premise that we decided to focus our research on some settlements that seem to us to be essential to address this general issue.

Until a few decades ago there was a lack of archaeological information on the existence of a stable military occupation for the period between the end of the Second Punic War and the end of the Celtiberian Wars. Only the camps of the siege of Numancia and the existence of stable military bases in Empúries and Tarraco were known, while for the rest of the territory of the northeast of the Iberian Peninsula there were no data that would modify this vision. It has often been stated that there are no stable military camps outside the conflict zones in these territories until the final decades of the 2nd century BC and the beginning of the 1st century BC, when greater instability began to take place in these territories as a result of the Cimbrian wars and the Sertorius revolt (Noguera et al. 2014).

In recent years, the development of new research projects has provided new data that allow us to propose the existence of stable military enclaves in the conquered territories from very early chronologies, together with settlements of an administrative nature related to the army.

Being a very extensive geographical area that has a wide typological repertoire of settlements, we will focus our article on the two sites that we have worked in the last decade and that could be representative of the northeast of the Citerior area, Can Tacó (Montmeló, Barcelona) and Puig Castellar (Biosca, Province of Lleida); two singular settlements of which we have sufficient archaeological documentation to try to define their typology (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Map of the situation of the two archaeological settlements (Pau de Soto).

Puig Castellar of Biosca (Catalonia, Spain). A Republican Fortress

Puig Castellar is located in the municipality of Biosca (county of La Segarra, province of Lleida), on a low hill situated at the confluence of three fluvial courses, currently very seasonal: the Riera de Biosca to the north; the Llobregós River, a tributary of the Segre, the major affluent of the Ebro River, and the Riera de Massoteres, to the south. The research project began in 2012 and has continued to date with different archaeological campaigns that took place in summer months (Pera et al. 2018, 2019: 22–23).

From the top of this hill there is a wide area of visual control, mainly of the Llobregós River valley; this privileged location gives to the settlement an exceptional strategic position to control the natural paths in a broad area in the central Catalonia.

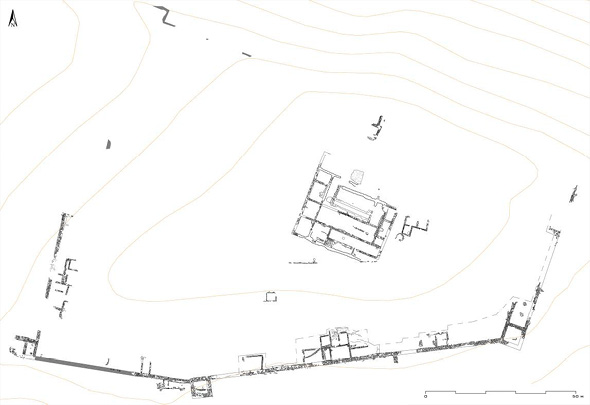

The excavation of the upper part of the hill of Puig Castellar, which forms a small plain, has made it possible to identify the remains of the main building that presided over the settlement, and the defensive wall that encloses it (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Map with the location of Puig Castellar fortress (Institut Cartogràfic i Geogràfic de Catalunya-ICGC).

The main building

The excavations have uncovered a large building of considerable dimensions (around 900 m2) with a square floor plan of 30.2 x 29.7 m, so that we can define a modulation pattern that follows the Roman foot (approximately 100 x 100 Roman feet). The building is organized with thirteen rooms, ranging from 12 to 104 m2, articulated around a 97 m2 beaten-earth central courtyard and framed in two of its sides (west and north wings) by a corridor, possibly arcaded (Fig. 3 and Fig. 4). The rooms in the south wing are located at a level lower than the rest; this obeys to an architectural solution that allows a better adaptation to the previously mentioned slope of the hill.

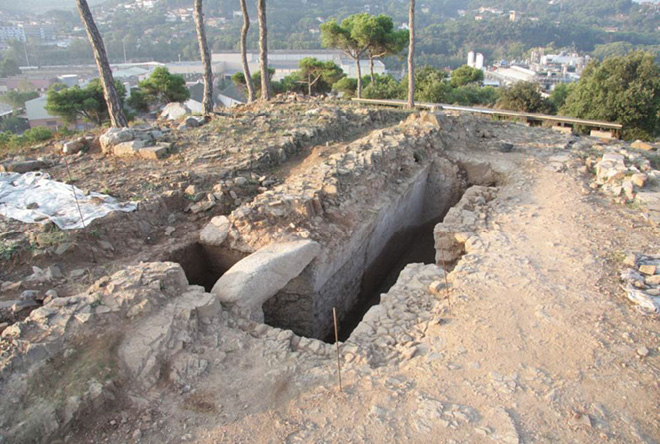

During the excavations of the courtyard a cistern was identified. It is a large rectangular structure dug directly into the natural rock which, unless the usual practice at the time, did not have any type of hydraulic coating for waterproofing because the geological chalks naturally retained the water. Only on its eastern boundary it is closed by a solid wall built with large ashlars (Fig. 4).

Inside the cistern, two filling phases were identified: the upper one, corresponding to the moment of abandonment, is formed by clay from the adobe elevations of the walls of the immediate rooms, preserving even some portions with the adobes in an articulated arrangement, all associated with a large amount of parietal wall building material (mouldings, painted stuccos) and some fragments of roof and pavements. The arrangement of these remains indicate clearly how they were demolished towards the interior of the cistern in an intentional way, contributing to its filling.

Fig. 3. Aerial view of the main building during the archaeological campaign of 2014 (Puig Castellar Team).

Fig. 4. Aerial zenital view of the main building after the 2014 excavation (Puig Castellar Team).

Regarding the construction techniques used on the main building, the remains recovered seem to indicate that the walls were raised with mud brick or adobe, arranged on a base of carved stones. We have been able to verify that at least one row of ashlars would rise on the stone foundations. The type of sandstone used in foundations and baseboards is of the same nature as that used for the construction of the defensive wall and were brought from outside, maybe from a nearby quarry unidentified.

The main building shows a diversity of pavements in opus signinum and cocciopesto in the different rooms. The artisans who built the pavements knew perfectly the constructive technique and made a careful choice of the materials to be used.

As for the parietal coatings, there is no doubt that, inside the noble rooms, the walls would be covered with stucco or painted plaster, mostly white and red (Romaní et al. 2020). The archaeometric analysis of some painted plasters also indicates a very elaborate execution technique. We have recovered numerous samples of them in the layers of demolition that filled the cistern and also in many of the surface layers of the site. Some of the fragments show bevelled reliefs and mouldings on its surface, probably related to the Pompeian First Style decoration.

According to the estimated chronology, we can present the settlement of Puig Castellar de Biosca as one of the first known sites in the use of these building techniques in Hispania.

The roofs were made with tegulae, despite the scanty sample documented until now in the settlement (6 fragments). The archaeometric analysis of two of the recovered fragments of tegulae has allowed us to determine its italic origin (Campania and Lazio) (Romaní et al 2020: 400–401).

The defensive wall

The excavation works in the area of the perimeter wall that surrounds the Puig Castellar hill (sector C) confirm that the settlement was enclosed by a defensive wall with four squared towers and two bastions.

The structure of the wall has a base of blocks of stone that are arranged directly on the natural rock cut, without clear indications of another type of foundation. It has a width in the base that ranges between 1 and 1.20 m and a conserved height of 80 cm (Fig. 6).

The best-preserved section is documented by the south side, and it is known in an extension of more than 250 meters. Its layout is not totally rectilinear: it adopts a slight inflection of a few degrees in its orientation in order to adapt to the natural topography of the hill (Fig. 5 and Fig. 6).

We have also documented the existence of some rooms that are arranged in battery and attached directly to the inner face of the southern wall. Even though currently it is not possible to determine the functions and uses of them because the archaeological work is yet in process, probably these rooms could be the barracks where the troops were quartered.

Fig. 5. General Plan of the archaeological site of Puig Castellar (Institut Català d’Arqueologia Clàssica).

Fig. 6. View of the defensive wall at south side (Puig Castellar Team).

The archaeological materials

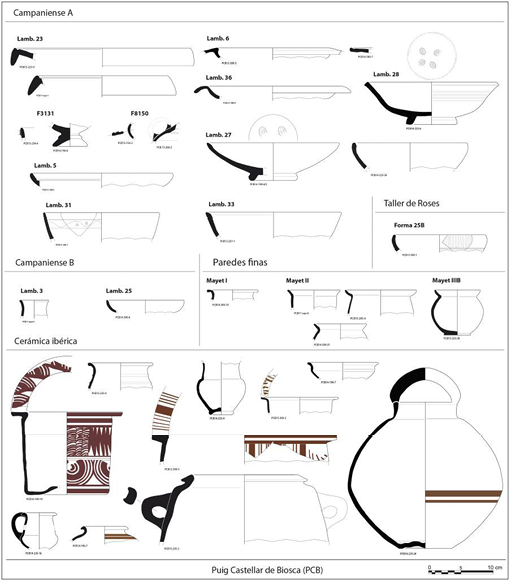

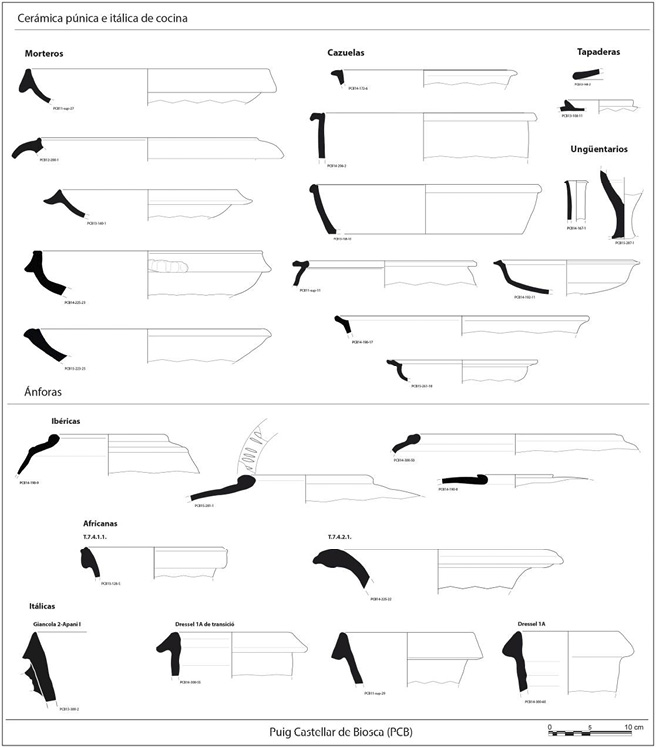

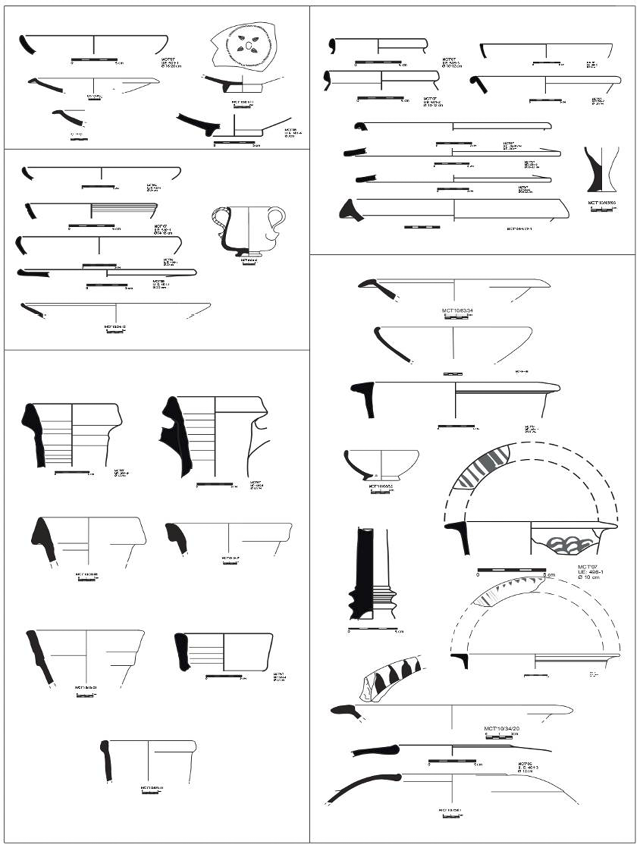

The excavations have provided an important ceramic set that marks a chronological horizon typical of the second and third quarter of the second century BC (Pera et al. in press); these materials are very representative of the interaction between the Roman and the indigenous worlds. In the studied stratigraphic contexts amphorae and pottery of Iberian tradition are widely represented, coexisting with an extensive ceramic repertoire of foreign origin, above all Italic.

Although the Iberian amphorae are predominant, the great amount of foreign amphorae productions can be observed, with a clear predominance of Italian amphorae; also, among the imported fine ware production the same predominance is detected. It is very relevant the great proportion of Campanian or black-gloss pottery from the group A that has been recovered, a great amount that could be surprising in a settlement that is located more than one hundred kilometres away from the coast, where it could be hard to supply with these imported goods.

Until now, the excavations have provided very few examples of metallic material, partly due to the intense clandestine activity that the site had been suffering for decades (Fig. 7 and Fig. 8).

Fig. 7. Fine imported ware and fine local pottery repertoire of Puig Castellar (Puig Castellar Team).

Fig. 8. Imported cooking ware and amphorae repertoire in Puig Castellar (Can Tacó team).

Only two coins from private collections can safely be attributed to Puig Castellar: one quadrans from Kesse (1st half of the 2nd century BC) and another from Arse (last quarter of the 2nd century BC).

Other metallic objects recovered in archaeological excavation are a bronze handle of a situla, coming from the cistern, three small bronze bolts and several drops of lead.

Among the materials of strictly military character, one bronze arrowhead with a central nerve and an iron horn of a long weapon were found.

As far as we know, Puig Castellar de Biosca can be considered a singular settlement, perhaps a castellum, a military establishment with an important historical significance due to the fact that it would be one of the earliest Roman military fortresses of the Iberian Peninsula. The military character of the establishment is beyond reasonable doubt, despite no significant remains of militaria have been identified. Its chronology, the location in height of the fortification, with an extensive visual domain of the territory, its considerable extension (1.6 ha), the singular typology of its main building, the existence of a defensive towered wall, the early use in Hispania of a series of noble building materials, such as terrazzo and opus signinum pavements, tegulae and imbrices of italic origin, painted and moulded stuccos, and, above all, a large amount of imported pottery are sufficient elements to support this interpretation.

If we analyse the architectural plan of the main building that presides over the settlement, we can see that it fits the constructive parameters of a command centre (principia?), a type of building that is documented in many military establishments although most of the examples known at present belong to the imperial period (Pera et al. 2019: 38).

In the same way, one fundamental aspect to consider is what could have been the main function of this settlement in the historical and territorial framework of the northeast peninsular area.

It should be remembered that, at the same time of the occupation of Puig Castellar de Biosca, Rome was involved in several wars in Hispania, such as the wars in Lusitania and Celtiberia, among which the long campaign of Numancia (154–133 BC) must be highlighted. In this context, it can be argued that Puig Castellar acted as a castellum from which the Roman Army exercised the control of one of the routes that linked the coast (Empúries or central coast) with the interior of the country. Following this approach, the fortress of Puig Castellar could have held a control function for the immediate territory and, above all, could have given logistical support, if necessary, to the troops that were traveling along this route. Its position in height, its defensive systems, its considerable extension and easy access from the valley fit perfectly to this purpose.

Another important aspect that we cannot ignore is the close relationship that we can establish between the end of the establishment and the foundation of the Roman Town of Iesso (Guissona), located only 6 kilometres away. It should be remembered that the foundational layers of the new Town indicate a chronology of the end of the 2nd century BC. For us it is clear the relationship between the two centres, Puig Castellar and Iesso, a thesis that is supported by the chronology and the serial succession of the materials that we have been able to study in both enclaves.

In this case we are facing a planned abandonment of the establishment, carried out in a well-ordered way. This would justify the absence of some constructive materials, since everything that could be reused (vessels, tiles, ashlars) does not appear in the recovered archaeological record. Although these are the first conclusions, we think that the establishment of Puig Castellar, together with its strictly military role, could have also functioned as the official headquarters of a Roman centre of territorial administration. If we take account of this function, it would not be strange to find high officials of the Roman administration living and developing their activity in these military installations, maybe some delegates of the Roman power that we do not discard that they formed part of the same military establishment. It would be these representatives of the Roman power who left their mark on the settlement, through the sumptuous details shown by the architecture and some of the products consumed.

Can Tacó (Montmeló-Montornès del Vallès, Barcelona). A fortified residential complex

The case of Can Tacó is another example of these first Roman establishments that emerges in the previous moment to urban foundations. The site currently belongs to two municipalities in the Vallès Oriental region (Montmeló and Montornès, Barcelona), a territory that in the 2nd century BC would correspond to the interior region of Iberian Laietania. Can Tacó is an archaeological site located at the top of a small hill that offers a wide visual domain of the natural corridor of the Vallès region through which the Ancient Via Heraklea (later Via Augusta) ran. The hill of Can Tacó is a spur of steep slopes that offer a natural defence to the settlement (Rodrigo et al. 2013a) (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9. Aerial view of the situation of Can Tacó (Institut Cartogràfic i Geogràfic de Catalunya).

The main building

The residential building of Can Tacó consists of two architectural bodies that show different orientations, although are enclosed by the same perimeter wall that delimits the entire architectural ensemble. This change of orientation is due to the need to adapt the construction of the buildings to the topography of the hill. It should be noted that the settlement has not been fully preserved and shows a high degree of destruction caused by natural erosion and a modern urbanisation attempt.

The total extension of the settlement covers an area of approximately 2,500 m². The settlement is adapted to the geological unevenness of the hill itself by arranging the different residential buildings on three tiered terraces.

Despite being the most eroded area of the complex and where the archaeological remains have been most damaged, we can affirm that the upper terrace formed a platform where the residential spaces of the settlement were located, occupying a main position. (Fig. 10).

Fig. 10. Aerial view with the archaeological plan of Can Tacó (Institut Català d’Arqueologia Clàssica-Mònica Mercado).

In this upper terrace, a large central open-air space with a cistern and a well, and three rooms around it, are identified. Also, we could assume the existence of many other accommodations that have not been preserved. It is in this area where the most outstanding dwellings of the settlement would be located, as it is suggested by the considerable number of white tesserae set in opus signinum and cocciopesto pavements that have been recovered.

At a lower level and on the eastern and western slopes of the hill, a second level of terrace is documented where there are located a battery of rooms (five in one side and three in the other side), that we have identified as service rooms, working spaces, and also storerooms.

Finally, a third terrace encircles the hill on the east, south and west sides, and would initially function as a circulation space since there are no building structures in this terrace, except for a second large capacity water reservoir built on the southern slope. This third terrace is delimited by a perimeter wall that closes the whole, built with a double-sided stone wall and an internal filling of earth and smaller stones, without showing this wall signs of fortification that may suggest its defensive use.

The secondary building

The second building would be formed by a large courtyard where the access to the main building is located. It would present two annex buildings where a total of ten rooms dedicated to domestic activities or storage have been found. We deduce from the preserved remains that the main access to the settlement was located on the north slope of the hill, although the existence of secondary accesses cannot be ruled out in other points of the site.

In terms of water consumption, the settlement dwellers were self-sufficient, since two connected cisterns coated with a fairly well-preserved opus hidraulicum are recorded, with sufficient water capacity to meet needs of the site (Fig. 11).

Fig. 11. The upper cistern of Can Tacó (Can Tacó team).

Building techniques

The buildings techniques and materials used are very homogeneous throughout the site. The hill of Can Tacó presents a geological composition of quaternary slates and degraded schist, which were used massively in the foundations in masonry of the walls (Fig. 12), occasionally combined with other stone materials taken from some nearby extraction areas, such as some granite blocks and river pebbles. On top of the stone foundation, the walls were raised using mud bricks and rammed earth, especially the interior walls that divided some rooms.

Fig. 12. The foundation in stone masonry of western wall of the room 7 (Can Tacó team).

The floors of the lodgings located in the lower terraces that we interpret as workspaces or warehouses, as well as the floors in the areas of passage, are made in beaten earth.

In the upper terrace, where the most luxurious rooms of the settlement would be located, we place the pavements made in opus signinum that have decorations with white tesserae. Unfortunately, we have only recovered two fragments of this type of pavement inside the upper cistern. In any case, on the surface layers, a few hundred tesserae have been collected, which are the clearest evidence of the existence of this typology of pavements.

Also, a large number of fragments of opus signinum and cocciopesto pavements have been recovered in the upper layers of the settlement.

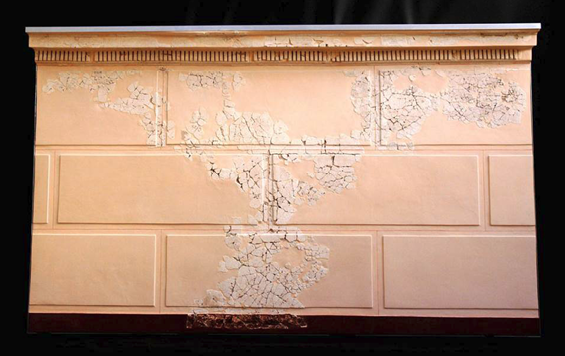

The decoration of these noble rooms would be completed with stuccos and mouldings that follow the techniques and decorative themes of the First Pompeian Style. Most of them were recovered fragmentarily at different points of the settlement and in the cistern itself. These remains of mural decorations are one of the most outstanding aspects that the excavations at Can Tacó have uncovered: a mural decoration that consists of the simulation of marble ashlars with stucco in relief, outlined by a painted red line, the fragmentary remains of what would be the base painted in dark red are also preserved, and the remains of cornices, denting mouldings, and beads and reel mouldings.

The exceptionality of these features together with the early chronology, on the first phases of the Roman occupation of the Iberian Peninsula, made of this site an exceptional study case (Fig. 13).

Fig. 13. The reconstruction of the mural decoration that corresponds with a First Pompeian Style (Can Tacó team).

As we have seen for Puig Castellar, tegulae and imbrices were used for the roofing. From the analysis of fabrics made by the Archaeometry Unit of ICAC-Tarragona, we have been able to verify that a part of this material comes from the Lazio-Campanian area. However, the large majority of tiles recovered were clearly locally produced (Rodrigo et al. 2013b).

The archaeological materials

Regarding the pottery assemblage, it is worth mentioning the chronological homogeneity corresponding to the moment of occupation. The imported tableware productions are well represented by the production of Italic black-gloss ware from the group A, many of the forms that have been recorded correspond to productions of the second third of the second century BC (Lamboglia 25, 27a, 31b, 33, 36). Due to the extended chronology of the Black-Glazed form repertoire it has been certainly difficult to accurately determine the initial moment of the settlement only considering this pottery type. The productions of Italic black-gloss ware of the so-called circle of the B appear in a proportion clearly inferior to the A vessels, and in its major part comes from the superficial strata or from the layers that correspond to final abandonment of the site. Among these, the early productions of this group, which are disseminated by the north-eastern peninsular region between the end of the second century BC and the first years of the first century BC, are predominant.

In the group of Italic imported coarse ware, we detect the presence of platters-lid, cooking pots and mortaria, which do not provide a more accurate dating for the site due to their wide chronology.

Another very abundant material in the settlement are the imported amphorae, especially from Italy, being the most characteristic the wine amphorae of the area of Campania (Dressel 1A) and the oil amphorae from Brindisi (Apani I and V) (Carreras 2016); the amphora types of the Greco-Italic variety are almost testimonial. Among the amphorae repertoire, the presence of three stamps on Rhodian amphorae repertoire must be highlighted because they provide a dating between 166 BC and 150 BC (Rodrigo et al. 2015). Also, we have a Punic stamp from Carthage that places us on a horizon prior to the destruction of Carthage in 146 BC.

The local Iberian ceramic vessels (kalathoi, dishes, bowls, jars), both painted and plain, are very abundant in the settlement and are present in a higher quantity than the imported ceramics. It must be noted that among these, numerous Iberian imitations of forms of the repertoire of the black-gloss pottery or Campanian ware have been identified (forms Lamboglia 25, 27, 36 and 33). Locally produced ceramic cooking pots and pans are also a widely represented material.

Together both the materials documented in the building construction strata, as in the occupation and abandonment strata of the settlement give us a chronological horizon from the second half of the second century BC to the first decades from the 1st century BC (Fig. 14).

Moreover, we have documented a few remains of militaria: a blade from a Gladius hispaniensis, a pointed butt spike that fitted a pilum, and one fragment of spearhead.

From the data provided by the excavations, we can reach the conclusion that Can Tacó is configured as another singular case of settlement from the first moments of the Roman presence; we consider that to its unequivocal residential character it is necessary to add the function of official representation tasks of the Roman power in this region, the Iberian Laietania.

We would highlight the strategic value of its location close to an important road hub that communicates the Catalan central coast with the interior territories, and likewise there is a broad visual domain over the immediate area and vice versa, that is, its elevated position constitutes a visual reference of the new power in the territory, especially for the Iberian communities.

Fig. 14. The ceramic repertoire of Can Tacó (Can Tacó team).

Starting from the documented architectural plan and the luxurious decorations of the building there is no doubt about the italic affiliation of its inhabitants and their high social status, aspects that we can relate to the presence in the settlement of an administrative elite, perhaps coming from the military itself. Despite this, we can discard a strictly military function of this residential complex, as had been suggested at the beginning of our research, due to the fact that there are no defensive walls and we consider that it clearly departs from the classic model of castellum. In any case, it would be a type of settlement for which we do not know exact parallels throughout the north-eastern Citerior Province for this period (2nd century BC).

The only explanation that seems feasible to us is its function as a residential complex that represents the new power and where it could have carried out administrative control over the territories of Laietania Interior.

Conclusions

The dating of Can Tacó (circa 165/150 BC to 90/80 BC) and Puig Castellar (circa 180–120 BCE) provides new data that allows us to fill in some of the gaps we have had for this period until a few years ago, especially the absence of permanent military settlements in the province of Citerior between 180 and 120 BC in areas far from both the battlefront and the military bases of Tarraco and Empuries. If until a decade ago the historiography and the archaeological data seemed to indicate a scarce deployment of the Roman army throughout the territory, since the last decade this vision has been gradually changing thanks to the location and excavation of new archaeological sites of an undeniable military nature.

As was stated before, the fortress of Puig Castellar fits perfectly to a Roman military-type installation, and its Roman affiliation would be reinforced by a well-defined chronology between 180 and 120 BC, since we consider that, in this period, only the Roman Administration would be able to establish a military fortress of this kind. Considering its chronology and features, it can be considered one of earliest and well documented examples of permanent military occupation of the Roman Army in the Iberian Peninsula.

In the case of the residential complex of Can Tacó, if we analyse the documented architectural plan and the luxurious decoration of the building, we have no doubt of the Italian affiliation of its inhabitants and their high social status, aspects that we can relate to the presence in the settlement of an administrative elite, perhaps coming from the military itself. Despite this, we can rule out a strictly military function of this residential complex, because there are no defensive walls and we consider that it clearly deviates from the classic castellum model. In any case it would be a type of settlement for which we do not know exact parallels throughout the NE for this period (2nd century BC).

Over the last decade, the number of recovered settlements from Roman Republic period in this region have increased considerably, the majority of them being of military nature (Fig. 14). In the area of Catalonia, it may be the recently excavated sites of Monteró (Camarasa, Lleida) (Principal et al. 2015), Sant Miquel de Sorba (Navès, Lleida) (Asensio et al. 2014), Puig Pelat (Puig Pelat, Tarragona) (Díaz, Ramírez 2015), Ilturo (Cabrera de Mar, Barcelona) (Martin 2006) Sant Julià de Ramis (Sant Julià de Ramis, Girona) and Mas Gusó (Bellcaire d’Empordà, Girona) (Casas et al. 2015) which show notable functional and typological similarities with both Puig Castellar and Can Tacó. In addition to the settlements afore-mentioned, other important sites of the north-eastern Hispania show some of its phases within this historical period: Olèrdola (Olèrdola, Barcelona) (Molist 2008), Sigarra (Els Prats de Rei, Anoia) (Salazar et al. 2016), Serrat dels Espinyers-Aeso (Isona, Lleida) (Belmonte 2015), El Camp de les Lloses (Tona, Barcelona) (Duran et al. 2015), Puig Ciutat (Oristà, Barcelona) (Padrós et al. 2015), Tarraco (Tarragona) (Ruiz de Arbulo 2015) and Empúries (Girona) (Castanyer et al. 2015), as well as others of lesser importance. All of them, although their existence could obey to other functions, should be considered for the global study of the first century of the Roman presence in the NE area of the Iberian Peninsula.

Finally, it is also important to highlight her participation as a member of the research team on the landscape of the Greek city of Emporion, a project that started in 2012 under the direction of Josep Maria Palet.

e-mail: esther.rodrigo@uab.cat

e-mail: nuria.romani@uab.cat

Funding: This research was funded by the Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities (De la consolidación del poder militar romana a la fundación de ciudades (mediados del siglo II a.C.-principios del siglo I d.C). en la Cuenca del rio Segre: Iesso y Iulia Libica DGYCIT PID2019-104120GB-I00-2023-2021), and the Department of Culture of the Catalan Autonomous Government (La conquesta romana a la Catalunya interior: l’exemple de Puig Castellar (Biosca), CLT009/18/00014).

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4771-1216

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4771-1216